eBay Isn’t Liable for Patent-Infringing Marketplace Sales–Blazer v. eBay

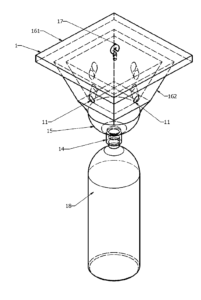

Blazer owns patent 8,375,624 for “Carpenter Bee Traps.” He filed NOCIs with eBay alleging the sale of infringing items on eBay. The court says “eBay has a policy to quickly remove listings when a [patent] NOCI provides a court order, but eBay rarely removes listings based on mere allegations of infringement.” Blazer never provided eBay with any court orders, so eBay didn’t act on his NOCIs. Blazer sued eBay for patent infringement.

Blazer owns patent 8,375,624 for “Carpenter Bee Traps.” He filed NOCIs with eBay alleging the sale of infringing items on eBay. The court says “eBay has a policy to quickly remove listings when a [patent] NOCI provides a court order, but eBay rarely removes listings based on mere allegations of infringement.” Blazer never provided eBay with any court orders, so eBay didn’t act on his NOCIs. Blazer sued eBay for patent infringement.

The court rejects Blazer’s patent infringement claims:

* Blazer conceded that eBay doesn’t “sell” the items because Sec. 271(a) defines sale as a transfer of property or title, and eBay doesn’t do either regarding marketplace sales.

* The court says there’s an “offer for sale” in eBay’s marketplace, but the court concludes the offer is made by its vendors, not eBay. The court distinguishes the Milo & Gabby v. Amazon case (which was a design patent case instead of a utility patent case, but apparently that didn’t matter) because “the context of an exchange on eBay demonstrates that no reasonable consumer could conclude that by bidding on an eBay listing, he was accepting an offer from eBay itself….Mr. Blazer has provided no direct evidence that eBay users believe that when they purchase an item on eBay’s website they purchase that item from eBay.”

* eBay lacked the knowledge to constitute inducement. “Mr. Blazer has failed to produce evidence that eBay had actual knowledge of infringement….eBay does not have expertise in the field of the patent or allegedly infringing products.” A willful blindness argument doesn’t work either. “No evidence suggests eBay was in possession of the critical facts necessary to form a subjective belief that a high probability of infringement was occurring…. Mr. Blazer has produced no evidence that eBay’s reason [for not investigating NOCIs] was a sham and that the real reason the policy existed was to blind the company to patent infringement.”

* The court says contributory infringement requires an “offer for sale” and requisite knowledge, and the prior discussion showed eBay had neither. The patent statute’s definition of contributory infringement differs from the common law rules in copyright and trademark; otherwise, this ruling wouldn’t make sense in those contexts.

Implications

Marketplace Liability for Patent Infringement. Remarkably, over the 20+ years of commercial Internet activity, we have had a tiny number of cases involving marketplace liability for transacting items covered by patents. The court only discusses two: Milo & Gabby v. Amazon and a 2012 ruling involving Alibaba. It might be surprising that such a fundamental question of Internet law remains unresolved in 2017, but this case could finally fill that gap.

Offer for Sale. This ruling is much cleaner than the lessons from the Milo & Gabby case. Regarding that case, I wrote: “should the trial conclude that Amazon did “offer for sale” the design patented items, then the holding will put significant pressure on Amazon’s characterization of its marketplace.” Fortunately for Amazon, the jury ruled for Amazon and the case fizzled out. In contrast, the holding in this case is clear and definitive–eBay isn’t the vendor or offeror of goods in its marketplace, so any patent liability must be secondary, not direct. To me, this is a persuasive ruling that should become the national standard.

Actual knowledge. The court says that eBay would have actual knowledge of infringing sales only if it got a copy of an injunction/court order enjoining sales of the patented items. The ruling implies that all other communications from the patentholder will not confer actual knowledge. This is a fantastic result from eBay’s standpoint, but it’s radically different than the corresponding rules for secondary copyright and trademark infringement, where NOCIs usually confer actual notice and impose a de facto or actual takedown obligation (but see the Tre Milano case as a rare exception). I can make an argument why patent scienter should be more stringent: it’s easier for an intermediary like eBay to do a visual comparison of a copyright or trademark than to dissect a patent. Indeed, we often don’t really know what the patent means until after claim construction, and because the Federal Circuit does a de novo review, we really don’t know the patent’s scope until that appellate ruling. Still, it would have been nice if the court had explained its patent exceptionalism rather than quietly imposing it.

Prospects on appeal. If appealed, this case will go to the Federal Circuit. Given their pro-patent biases, I’m skeptical the Federal Circuit will issue an opinion as defense-favorable as this one.

Trend in Favor of Marketplaces. This is another court ruling in favor of marketplaces. We’ve seen a few troubling rulings for marketplaces recently, including the Airbnb and McDonald v. LG rulings. However, overall, the trend line for online marketplace liability is in a positive direction for them. 20 years ago, it was uncertain if online marketplaces could avoid enough legal liability to survive. I think the answer to that question is clearer now.

This ruling nicely illustrates the pro-marketplace trend. If marketplaces faced patent liability risk for marketplace transactions, then (a) because patent infringement is strict liability, they would be imperiled by lawsuits they couldn’t really avoid, and (b) even if courts or Congress fashioned a rule that wasn’t strict liability, overzealous NOCIs could easily wipe the marketplace clean of competitors, making the marketplace less useful (or not useful at all) to consumers. I think there are good reasons to question patent law’s strict liability standard and its imposition of equal liability on infringing manufacturers and unwitting retailers. Who knows if those doctrinal rough edges will ever get fixed, but at least online marketplaces have a sensible rule (until the Federal Circuit messes it up).

Note #1: The defense team in this case was Ian Ballon and Josh Raskin, assisted by Justin MacLean and Amy Kramer, from Greenberg Traurig. When a district court patent opinion reads this cleanly and elegantly, especially in a venue like northern Alabama where judges don’t see a lot of patent cases, you know the litigators did a terrific job explaining the law and the case to the judge. And kudos to eBay for navigating this case to a better result than Amazon got in its Milo & Gabby case, as well as their many key contributions to Internet IP jurisprudence–including the eBay v. MercExchange case, which remains a milestone case in Internet patent law.

Note #2: I still own some IPO shares of eBay.

Case citation: Blazer v. eBay, Inc., 2017 WL 1047572 (N.D. Ala. March 20, 2017)