Handicapping the Olympic Committee’s Quest to Control Tweeting (Guest Post)

By guest blogger Prof. Alexandra Jane Roberts

[Eric’s intro: the Rio Summer Olympic games may be over, but the legal wranglings from the games will keep going and going–even longer than the bike road race (and perhaps with as many crashes). And, of course, the Olympic organizers are already planning to set new world records for ridiculously tendentious legal positions for the PyeongChang 2018 Winter Olympics and beyond. In this post, Prof. Roberts analyzes the Olympic Committee’s efforts this year to crack down on tweeting certain terms.]

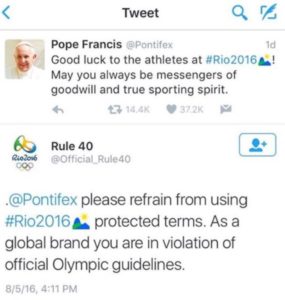

In 2016, companies and brands aren’t just tweeting about the Olympics. They’re subtweeting the US Olympic Committee for telling them not to tweet about the Olympics.

The USOC was particularly aggressive about enforcing its trademarks in the days leading up to the summer games in Rio. Its cease & desist letters informed companies that if they were not official Olympic sponsors, they were forbidden from “post[ing] about the Trials or Games on their corporate social media accounts” or even “us[ing]…USOC’s trademarks in hashtags such as #Rio2016 or #TeamUSA.”The USOC’s letter “further stipulates that a company whose primary mission is not media-related cannot reference any Olympic results, cannot share or repost anything from the official Olympic account and cannot use any pictures taken at the Olympics.” In other words, even retweets are ostensibly prohibited. In addition, the USOC’s Olympic and Paralympic Brand Usage Guidelines ban companies that are not official sponsors from “us[ing] any USOC trademarks in any form of advertising (e.g., on a website, in social media, etc.)” or “creat[ing] social media posts that are Olympic themed, that feature Olympic trademarks, that contain Games imagery or congratulate Olympic performance.”

The Zerorez Litigation

A Minnesota carpet cleaning company, Zerorez, heeded the warning and refrained entirely from posting about the Olympics on social media. Instead, it sued the USOC in federal court for a declaratory judgment affirming its right to engage in Olympic-related chit-chat and to cheer for Olympians that hail from its home state. Viewers and commentators eagerly anticipated resolution.

Unfortunately, the case is a non-starter—like French hurdler Wilhem Belocian, Zerorez will likely be disqualified on a technicality. In order for a federal court to have jurisdiction over a dispute, an actual case or controversy must exist between the parties. The USOC’s actions vis-à-vis other companies do not create a live controversy with Zerorez. A case or controversy can arise where a party is actively threatened with litigation—if Zerorez tweeted from its corporate account, “Congrats to the 11 Minnesotans competing in 10 different sports at the Rio 2016 Olympics! #rioready” and the USOC sent it a letter saying, “Delete your tweet about the Olympics or we’ll sue you for trademark infringement,” then Zerorez could likely establish that a ripe controversy underlies its declaratory judgment action.

But the company only alleges that it “anticipated discussing the Olympics on its social media accounts”—it never actually posted such comments. That anticipation is almost certainly not enough to satisfy justiciability requirements.

So those hoping a court will rule on whether the USOC is applying trademark law overzealously will probably have to keep waiting. USOC’s response to the Zerorez complaint is not due until August 30th, more than a week after closing ceremonies in Rio, and those closing ceremonies will make the existence of a controversy nearly impossible for even a sympathetic court to locate. Smart money says the USOC will file a motion to dismiss and the court will throw the case out without hearing it.

Is the USOC a Trademark Bully?

Constraints of subject matter jurisdiction aside, what about the USOC’s assertions that it has the right to silence any company who simply wants to support and celebrate American athletes or participate in the global conversation around the Olympics? Is it over-exaggerating? Critics have been quick to paint the USOC’s assertions of its rights as “ridiculous,” “completely bogus,” and “bullsh-t” unsupported by trademark law. This blog’s own Eric Goldman thinks “trying to tell companies that they can’t use the hashtag #Rio2016 or #TeamUSA in their tweets, most of the time…go[es] far afield of what the law permits” and constitutes “bullying.”

But can commercial entities simply dismiss the USOC’s claims as overreaching? The USOC has federally registered a number of trademarks, including RIO 2016 (design mark) and TEAM USA. Under the Lanham Act, the federal statute that governs trademark use in the US, anyone who uses a registered mark in commerce “in connection with the sale…or advertising of any goods or services on or in connection with which such use is likely to cause confusion, or to cause mistake, or to deceive” will be liable. Critics dispute the USOC’s infringement assertions on two grounds: they argue that using Olympic trademarks on social media in a post that doesn’t directly try to sell anything is not necessarily commercial, and that such social media posts are unlikely to confuse or mislead the public.

The USOC predicted these objections. In response to an email inquiry from a non-sponsor seeking clarification of the rules regarding whether it would be permissible for her to “discuss the Olympics…on social media,” the USOC informed her:

[U]nless a company or organization’s primary business is disseminating news and information, the company’s social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, SnapChat, Instagram, etc.) are commercial in nature, serving to promote the company or brand; to raise the brand’s profile and public opinion about the company or organization; and/or to increase sales, membership or donations. Thus, any use of Olympic or Paralympic trademarks or terminology by a non-media company – whether in traditional advertising, on its website, or through social media – is considered commercial and is prohibited without the USOC’s permission.

In other words, the USOC argues that if a social media account belongs to a corporation rather than an individual, all posts are inherently commercial in nature, rendering any use of Olympic trademarks a use “in advertising.” And because members of the public are generally aware that some companies pay for the right to be official Olympic sponsors—to the tune of $200 million apiece—they may be susceptible to confusion as to which brands can boast of that status.

The assertion that every social media post from a company account constitutes advertising or commercial speech is probably a stretch. The definition of commercial speech is difficult to nail down. The Supreme Court has defined it in several different ways, including “speech that proposes a commercial transaction” and “expression related solely to the economic interests of the speaker and its audience.” If an American company that sells pencils shares an article headlined “Is Simone Biles the best gymnast ever or just the best gymnast on the planet?” with the hashtag #Rio2016, it may “raise the brand’s profile” as the USOC alleges, at least among Biles fans. But it isn’t clear that suffices to render it commercial speech or advertising.

Moreover, the Olympic references that Zerorez contemplated are unlikely to confuse consumers. The Olympics in Rio captured the world’s attention, dominating a news cycle that included a devastating flood in Louisiana and various presidential campaign shenanigans. Consumers are probably savvy enough that they would not assume a company’s merely mentioning an event that’s trending on social media implies sponsorship, endorsement, or any particular relationship between the company and the event. Of course, there are plenty of ways for companies to deceive consumers as to the existence of such a relationship, but the USOC’s blanket ban on “posting about the Games” or using any Olympic-related hashtags is far too broad to exclude only those deceptive posts. Social media users expect hashtags, in particular, to be democratic—my study suggested users perceive online hashtags as inviting everyone to participate in global conversations on topics of shared interest.

Trademark law recognizes that there are many ways to use another’s mark without misleading consumers or infringing the owner’s rights. Under the descriptive fair use doctrine, a trademark can be used in its dictionary sense to describe the speaker’s own goods and services—that’s why Ocean Spray can market its cranberry juice as “sweet-tart” without infringing Nestle’s SweeTart trademark for candy. So while the USOC has registered TEAM USA for everything from coffee mugs to cowbells, others can arguably use the hashtag #TeamUSA or the phrase “team USA” descriptively when they talk about athletes who represent the United States in the Olympics.

Trademark law also typically permits speakers to use a trademark to reference the brand or company the mark identifies. That type of use is known as “nominative fair use,” and it helps ensure the label on Target’s Up & Up brand shampoo can say “compare to Head and Shoulders®” and the website for Bose headphones can advertise that they are “compatible with most iPod and iPhone models.” The test varies slightly depending on jurisdiction, but typically requires that 1) the goods or services in question—here, the Olympics—are not readily identifiable without use of the trademark; 2) only so much of the mark is being used as is “reasonably necessary” to identify the goods or services; and 3) the user does nothing that would suggest sponsorship or endorsement.

We would expect most Olympic references on social media to be permissible under one or both of the fair use frameworks. Hashtags in particular serve the function of grouping content on sites like Twitter and Instagram, enabling commercial speakers to participate in the conversation about the Olympics in ways consistent with those sites’ community norms. Their technical function may also mean they fail to satisfy the trademark “use” (as a mark) requirement that some jurisdictions impose for a successful infringement claim.

If the trademark owner under consideration were a company like Nike or Starbucks, the analysis would probably end here, and we could reasonably label the brand a trademark bully for threatening legal action over non-confusing fair uses.

The Olympic and Amateur Sports Act

But the trademark owner is the USOC, and Congress has granted the Committee special trademark rights that go above and beyond those the Lanham Act confers. The Ted Stevens Olympic and Amateur Sports Act, 36 U.S.C.S. § 220506, grants the USOC the “exclusive right to use” various marks associated with the Olympics and authorizes it to pursue a civil action against anyone who uses the protected marks or any simulation of them in commerce “to induce the sale of any goods or services.”

That statute is not inconsistent with the Lanham Act on its face. But courts enforcing it have dispensed with two crucial safeguards that usually serve to keep trademark law in check. First, the USOC need not show a defendant’s use creates a likelihood of consumer confusion, usually the hallmark of a successful trademark infringement cause of action. And second, statutory defenses are unavailable. [San Francisco Arts & Athletics, Inc. v. United States Olympic Comm., 483 U.S. 522, 531 (1987).] (Note that nominative fair use is not an explicitly statutory defense, so this line of cases does not definitively foreclose its availability.)

Federal courts have held that “the protection afforded to Olympic symbols is broader than the rights provided under the Lanham Act, effectively providing the [USOC] with an exclusive right in the Olympic words and symbols.” [United States Olympic Comm. v. Xclusive Leisure & Hospitality Ltd., 2009 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 12698, *12 (N.D. Cal. Feb. 19, 2009).] And while OASA appears as though it was designed to limit that robust protection to the marks enumerated in the statute, including OLYMPICS and the Olympic rings, at least one court has controversially interpreted it to extend protection to other marks that reference the Olympics, such as BEIJING 2008 [id.]. While other courts are unlikely to follow suit, that case sets a troubling precedent given the hundreds of marks to which the USOC might plausibly lay claim.

If OASA sounds like it confers “unfettered control over the commercial use of Olympic-related designations,” perhaps that’s precisely what Congress intended. [U.S.O.C. v. Intelicense Corp., 737 F.2d 263, 266-67 (2d Cir. 1984).] Courts have acknowledged that the USOC is the only national Olympic committee that does not receive formal financial assistance from the government and, consequently, additional trademark protection is justified. [Id.] While the idea of such unfettered control of terms and symbols irks critics on First Amendment grounds, the Supreme Court has held that, because it applies primarily to commercial speech, OASA is “well within constitutional bounds.” [San Francisco Arts & Athletics at 535, 536 n.15.] According to SCOTUS, “Congress reasonably could conclude that most commercial uses of the Olympic words and symbols are likely to be confusing. It also could determine that unauthorized uses, even if not confusing, nevertheless may harm the USOC by lessening the distinctiveness and thus the commercial value of the marks.” [Id. at 539.]

Courts have allowed referential uses of Olympic trademarks as long as they were noncommercial, as in one case regarding the “Stop the Olympic Prison” campaign and another over a magazine entitled “Olympics USA.” [Stop the Olympic Prison v. U.S. Olympic Comm., 489 F. Supp. 1112 (S.D.N.Y. 1980); U.S. Olympic Comm. v. Am. Media, Inc., 156 F. Supp. 2d 1200, 1202 (D. Colo. 2001).] But the USOC could make a colorable claim that a non-sponsor’s use of Olympic trademarks and hashtags on social media is at least a little bit commercial, and thus runs afoul of OASA and the cases interpreting it.

Since 2013, companies have been registering hashtags as trademarks with the USPTO. I’m skeptical that consumers perceive online hashtags as distinctive trademarks; parties that have sued over hashtag use have found some courts equally skeptical that hashtag use can infringe trademark rights. But in neither requiring a likelihood of confusion nor tolerating fair use defenses, OASA confers protections that are far more robust than those the Lanham Act provides. The USPTO defines a trademark bully as an owner who “uses its trademark rights to harass and intimidate another business beyond what the law might be reasonably interpreted to allow.”

While the USOC defies social media norms about hashtags in ways the majority of the population finds odious, it may not technically be a trademark bully in warning companies to avoid the word “Olympics.”

Pingback: Sports Law Links – The Sports Esquires()