Top 10 Fair Use Cases of 2014 (Guest Blog Post)

[Eric’s introduction: in my blog post on the copyrightability of resumes, I observed that “2014 has been a terrific year for fair use” and mused that “It would be great if someone did a ‘top 10 fair use rulings of 2014’ post.” Normally, such musings have as much impact as a cannonball landing in a bog, but not this time! Dan Nabel, visiting assistant clinical professor of law and interim director of the Intellectual Property & Technology Law Clinic at the USC Gould School of Law, offered to compile such a list. I’m pleased to share it here with you.]

By Dan Nabel

This year, fair use law experienced mostly positive developments. The biggest trend, which harkens back to Bill Graham Archives v. Dorling Kindersley Ltd., 448 F.3d 605 (2d Cir. 2006) and Perfect 10, Inc. v. Amazon.com, Inc., 508 F.3d 1146 (9th Cir. 2007), involves fair use findings in cases where the new work transforms the “function or purpose” of the original work without altering or actually adding to it. We saw a series of decisions concluding that aggregating content (e.g., television clips, digitized books, legal briefs, etc.) into searchable databases for new uses can be transformative, even if little or nothing about the original content itself changes. In another, more disturbing trend, we continued to see cases where people acquired copyright registrations for the sole purpose of trying to silence their critics. Thankfully, in each of these cases, fair use (even when poorly applied by Judge Easterbrook) protected freedom of speech. Finally, we saw a biographical film about the life of a pornography actress protected for its critical content and an even-handed (albeit monstrously long) opinion involving digital coursepacks at Georgia State University.

Without further ado, these are my “Top 10” fair use cases for 2014 in chronological order:

1. January 27 – Swatch Grp. Mgmt. Servs. Ltd. v. Bloomberg L.P., 756 F.3d 73 (2d 2014)

Back in 2011, this case gave rise to a new, irresistibly silly law school exam question: If a tree falls in a forest and the logger chopping it down records the sound, while a nearby reporter simultaneously makes her own, independent recording, who owns the copyright to the sound of the falling tree?

The real facts here involved two different sound recordings of a Swatch company conference call where company executives discussed year-end financial figures with a few hundred investors and analysts. Although Swatch (which recorded the call) asked its attendees not to record the call, a Bloomberg infiltrator did just that. Bloomberg then distributed the recording—which contained some embarrassing remarks about a Swatch business partner—to Bloomberg’s subscribers. Swatch promptly registered a copyright in its own sound recording and sued.

The 2011 district court opinion dealt with numerous interesting issues. On a motion to dismiss, Bloomberg had argued that: (1) it made its own, independent recording of the conference call so it did not “copy” anything (the genesis for my law school exam question); (2) Swatch’s recording lacked sufficient originality to qualify for copyright protection; (3) Swatch failed to comply with the Copyright Act’s pre-fixation notice requirement; and (4) in any event, fair use provided a complete defense. (Attorney David Kluft does an excellent job discussing the outcome of the motion here.) Later in the case, the district court granted summary judgment sua sponte in favor of Bloomberg exclusively on fair use grounds. Swatch appealed.

For procedural reasons, the court of appeal only reached the issue of fair use and affirmed the district court’s grant of summary judgment. The appellate court reasoned that (1) the Bloomberg recording didn’t harm “the original author’s legitimate copyright interests” and was arguably transformative in “function or purpose” because Bloomberg sought to publish factual information to an audience that Swatch wanted to hide the information from; (2) the public sharing of the information during the conference call made the publication status of the recording favor fair use; (3) the third factor was neutral in light of the transformative use despite the entire amount being “copied”; and (4) Swatch didn’t have any legitimate market for conference call recordings that Bloomberg had harmed.

While it would have been much more interesting to see an appellate discussion of the other issues raised in Bloomberg’s motion to dismiss, at least we got a good fair use decision.

2. February 25 – Dhillon v. Does 1-10, No. C 13-01465 SI, 2014 WL 722592 (N.D. Cal. Feb. 25, 2014)

Charles Munger, Jr. is an active force in reshaping the Republican Party in California. Governor Brown once called him and one of his politically active sisters “billionaire bullies.” Munger has also irked fellow Republicans who feel he’s too liberal. He’s even inspired a blog called “The Munger Games: ‘Wasting His Patrimony.’”

On February 12, 2013, The Munger Games posted an article questioning Munger’s support of Harmeet Dhillon, a liberal San Francisco attorney contending for the Vice-Chairman position in the California Republican Party. The article—which contained a headshot of Dillon—criticized her and her connections with a despicably progressive organization, the (gasp!) ACLU.

On February 21, 2013, Dhillon registered a copyright for her headshot which she had commissioned for political marketing. Apparently having moved on from the ACLU and its mission of protecting civil liberties, she then tried to squelch the negative article. Since she couldn’t determine who operated the blog, she sued “Does 1-10” and obtained a subpoena for the ISP. Several months later, still not knowing the true identity of the blog’s operators, she lost a summary judgment motion filed anonymously by “Doe 1.”

Doe 1 won easily on fair use grounds. The court found that the original purpose of the headshot was to promote Dhillon politically whereas The Munger Games used it for the exact opposite purpose—to criticize her. Dhillon also failed to even allege that “any market ever existed for the sale or licensing of the headshot photo, or that such a market might have developed at any future time.”

Ironically, I’m pretty sure the ACLU would approve of this result.

3. May 4 – Caner v. Autry, No. 6:14-CV-00004, 2014 WL 2002835 (W.D. Va. May 14, 2014)

In 2005, the reverend Jerry Falwell hired born-again Christian Ergun Caner to serve as a dean of the Liberty Theological Seminary in 2005. In the ensuing years, Caner fabricated claims that he had been raised as a radical Muslim jihadist in Turkey despite having previously written a book and made speeches describing his childhood in Sweden. The Seminary formed a committee to investigate Caner and eventually demoted him. Adding insult to injury, one of his fellow theologians, Jonathan Autrey, posted two videos of Caner on YouTube in an attempt to expose Caner’s lies. Caner sent a takedown notice to YouTube; Autrey contested the notice; and Caner sued Autrey.

Caner argued, while seeking more discovery, that Autrey wasn’t “qualified” under the fair use doctrine to criticize him. The district court called Caner’s argument “spurious” and “ludicrous on its face,” observing that the First Amendment’s protections (as advanced by the fair use defense) “have never applied to some bizarre oligarchy of ‘qualified’ speakers.” (Read the full benchslap here.)

The district court unequivocally concluded that posting YouTube videos to criticize and expose someone as a liar qualifies as fair use. The court stated that “it has long been established that fair use protects the transformative use of a work to criticize, even when the parody or criticism is so forceful that it may eliminate the market for the object of the criticism.”

Venkat’s blog post on the case.

4. June 10 – Authors Guild, Inc. v. HathiTrust, 755 F.3d 87 (2d Cir. 2014)

For anyone wondering about the future of Google books, this case provides a decent sneak-peak.

In 2004, several universities agreed to allow Google to scan the books in their collections. In 2008, these institutions created an organization called HathiTrust to operate the newly created HathiTrust Digital Library (HDL) which included digital versions of “more than ten million works, published over many centuries, written in a multitude of languages, covering almost every subject imaginable.”

HathiTrust allowed three categories of users to access its works.

First, members of the general public could search for terms across the entire repository. The search results contained book titles and page numbers containing the relevant terms. Unlike Google books, however, the HDL does not display any text (either in “snippet” form or otherwise). Instead, the results look like this:

Second, member libraries could provide their patrons with certified print disabilities (e.g. blind people) access to full texts of copyrighted works so that they could obtain access to the contents through adaptive technologies such as text-to-speech software.

Third, the HDL retained digital copies for its members to use as backups provided “(1) the member already owned an original copy, (2) the member’s original copy is lost, destroyed, or stolen, and (3) a replacement copy is unobtainable at a fair price.”

In 2011, twenty authors and authors’ associations sued HathiTrust (and others) for copyright infringement.

In 2012, the district court granted summary judgment on the basis that all three uses permitted by HDL were fair, giving considerable weight to the transformative nature of the uses and HDL’s “invaluable” contribution to the advancement of knowledge.

The appellate court affirmed for the first two uses (i.e., digitizing copyrighted works to permit full-text searches and full access to print-disabled patrons). The court found not only that the uses were “quintessentially transformative,” under factor one, but also, under factor four, that “[l]ost licensing revenue counts…only when the use serves as a substitute for the original and the full-text-search use does not.” For the third use (i.e., the digital backup copy), the court held that the authors had failed to present sufficient evidence of standing, as a threshold issue, and remanded the case back to the district court without addressing the substantive claim.

5. June 17 – Katz v. Chevaldina, No. 12-22211-CIV-KING, 2014 WL 2815496 (S.D. Fla. June 17, 2014), report and recommendation adopted, No. 12-22211-CV, 2014 WL 4385690 (S.D. Fla. Sept. 5, 2014)

As Prof. Goldman wrote back in June, this case is yet another example of someone acquiring a copyright for the sole purpose of trying to suppress content they don’t like.

In this case, a Florida woman ran a blog dedicated to criticizing one of the wealthiest men in Miami—her former landlord, Raanan Katz, a business man who owns shopping centers in Florida and New England and a minority stake in the Miami Heat. The blogger (who had a commercial property dispute with Katz years earlier and at one point had eight separate lawsuits with him) wrote about landlord-tenant issues and other unfair business practices (including racial discrimination) that Katz and his company engaged in. The spurned tenant included a photograph of Katz that she obtained from a Google search in many of her articles, sometimes modified with harsh superimposed text or mocking imagery. The photograph originally appeared in an Israeli news article which discussed Katz’s activities in Israel. Katz obtained the rights to the photograph from the photographer and used it to try and silence the blogger on copyright infringement grounds.

As Prof. Goldman observed, this was an easy fair use case. But what’s really upsetting is that Katz may still have won the war. At the district court level, he obtained a preposterous injunction ordering the blogger “not to enter defamatory blogs in the future” as well as an injunction against trespassing and stalking on the grounds that the blog posts constituted “cyberstalking.” As a practical matter, this prevented the blogger (and her husband) from either criticizing Katz or stepping foot on any of his properties (which basically meant most of the local businesses in the town they lived in). Although an appellate court vacated the injunction, the blog—and all of the blogger’s criticism—has been taken offline.

Seems like a Pyrrhic victory for fair use and free speech.

6. July 3 – White v. W. Pub. Corp., 12 CIV. 1340 JSR, 2014 WL 3057885 (S.D.N.Y. July 3, 2014)

This class action copyright infringement lawsuit finally answered the question: Can Lexis and Westlaw aggregate publicly-filed legal briefs for their subscription-only searchable databases without permission from the lawyers who authored the briefs?

Yes.

In a relatively short opinion, Judge Rakoff explained that Westlaw and Lexis transformed both the purpose and character of the briefs. While plaintiffs created the briefs to provide legal services to clients and obtain specific legal outcomes, Westlaw and Lexis used them to create “an interactive legal research tool.” Editing the briefs and adding coding, links, etc., also gave them “something new” and imbued them “with a further purpose or a different character.” (Much like Elle Woods’ scented, pink resume.)

The second factor favored Westlaw and Lexis because plaintiffs had already made the briefs publicly available by filing them with courts. The third factor favored neither party because even though Westlaw and Lexis copied entire briefs, the copying was necessary in light of the transformative purpose.

The fourth factor also favored Westlaw and Lexis because the plaintiffs hadn’t lost any clients and no market existed for the plaintiffs to license their briefs. Additionally, “no potential market existed because the transaction costs in licensing attorney works would be prohibitively high.”

Eric’s blog post on the case.

7. August 25 – Arrow Prods., LTD. v. Weinstein Co. LLC, No. 13 CIV. 5488, 2014 WL 4211350 (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 25, 2014)

How far has the Second Circuit come since Debbie Does Dallas?[1] Thirty-five years later, we get an opinion involving Deep Throat, and plenty of progress.

[1] Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders, Inc. v. Pussycat Cinema, Ltd., 604 F.2d 200, 206 (2d Cir. 1979) (affirming injunction of pornographic film which infringed trademarked uniforms of Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders)

In the most titillating fair use opinion of 2014, the Second Circuit examines trademark and copyright infringement claims brought by Arrow Productions, the producer and distributor of the well-known pornographic film, Deep Throat, against (my former clients) the Weinstein Company for their film, Lovelace, a biographical work about Linda Lovelace (the famous star of Deep Throat).

The Weinstein Company copied three famous scenes from Deep Throat by recreating the dialogue, positioning of actors, and even the camera angles. Nevertheless, the Second Circuit found the copying transformative because it added “a new, critical perspective on the life of Linda Lovelace and the production of Deep Throat.” The Second Circuit observed, among other things, that Lovelace provided (1) “a behind-the scenes perspective on the filming of Deep Throat,” (2) “does not contain any nudity,” and (3) included the copied scenes “in order to focus on defining part of Lovelace’s life, her starring role in Deep Throat.”

The Second Circuit also discounted Arrow Productions’ very specific market harm argument that it had licensed the use of Deep Throat to creators of a competing documentary about Linda Lovelace. Arrow argued that once the press began to report about Lovelace, the competing documentary never got funded and Arrow lost licensing revenue from that project. The Second Circuit found that this claim “must fail because defendants’ film Lovelace clearly constitutes a transformative use of the copyright film Deep Throat” and, accordingly, Arrow “cannot prevent defendants from entering this fair use market.”

[Eric’s comment: I liked the opinion better than I liked the movie.]

8. September 9 – Fox News Network, LLC v. TVEyes, Inc., 13 CIV. 5315 AKH, 2014 WL 4444043 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 9, 2014)

For the last few years, I’ve had a bumper sticker attached to my refrigerator that reads: “FOX NEWS, When Facts Don’t Matter.”

This case reaffirms my decision to keep it there.

TVEyes records content (including Fox News content) from more than 1,400 television and radio stations 24/7 and aggregates it into a searchable database for its subscribers. TVEyes lets its subscribers obtain text transcripts and video clips containing the search terms used. In 2013, TVEyes had “over 2,200 subscribers including the White House, 100 current members of Congress, the Department of Defense, the United States House Committee on the Budget, the Associated Press, MSNBC, Reuters, the United States Army and Marines, the American Red Cross, AARP, Bloomberg, Cantor Fitzgerald, Goldman Sachs, ABC Television Group, CBS Television Network, the Association of Trial Lawyers, and many others.”

Fox News didn’t like the fact that the TVEyes service used Fox News’ content without permission. It sued for copyright infringement and sought an injunction.

The district court denied the request for an injunction on fair use grounds (although it carved out certain features, e.g., allowing clips to be archived, downloaded, emailed, and shared via social media for more fact-finding and later determination). Unsurprisingly, the court faithfully followed Authors Guild in making its transformative use determination. But the part of the opinion dealing with market harm is why I have that bumper sticker on my fridge. The court observed:

Fox News’ allegations assume that TVEyes’ users actually use TVEyes as a substitute for Fox News’ channels. Fox News’ assumption is speculation, not fact. Indeed the facts are contrary to Fox News’ speculation.

The court then goes on to explain, in great detail, how “[t]he record does not support Fox News’ allegations” and how “Fox News fails in its proof that TVEyes caused, or is likely cause, any adverse effect to Fox News’ revenues or income from advertisers or cable or satellite providers.”

This case proves that (at least in fair use cases) facts do matter.

[Eric’s comment: we’ll see how this case fares in the Second Circuit. For now, I’ll rank this as my biggest fair use win of 2014, and it will almost certainly make my list of top 10 Internet Law developments of 2014.]

9. September 15 – Kienitz v. Sconnie Nation, LLC, 766 F.3d 756 (7th 2014)

Back in February, Judge Easterbrook earned AboveTheLaw.com’s “Bench Slap of the Day” award for some harsh language directed at defense counsel in a bank robbery case.[2] Several months later, perhaps seeking to outdo himself, Judge Easterbrook delivered some less vituperative, but equally powerful criticism, this time directed at the 2d Circuit and its fair use opinion in Cariou v. Prince, 714 F.3d 694 (2d Cir. 2013).

[2] In U.S. v. Johnson, 745 F.3d 227, 232 (2014), Easterbrook sanctioned the defendant’s attorney $2,000 and wrote that the attorney “may not have set out to develop a reputation as a lawyer who word cannot be trusted, but he has acquired it” and further threatened the opinion served “as a public rebuke and as a warning that any further deceit will lead to an order requiring [the attorney] to show cause why he should not be suspended or disbarred.”

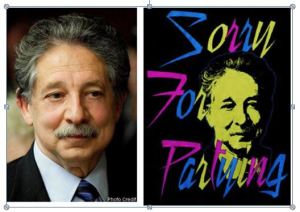

The 7th Circuit, to its credit, first gave an excellent recitation of the relevant facts. In short, a professional photographer took an official photograph of a mayor, then sued an amateur t-shirt company for incorporating the photograph into a gag t-shirt that poked fun at the mayor:

The 7th Circuit, also to its credit, affirmed the district court’s fair use judgment. Sadly, in doing so, it dumped the magistrate judge’s perfectly decent fair use analysis and replaced it with drivel.

The 7th Circuit boldly announced that it was “skeptical of Cariou’s approach,” and reasoned that although the U.S. Supreme Court “mentioned” transformative use in Campbell, the term does not appear anywhere in the text of 17 U.S.C. 107 and, moreover, “also could override 17 U.S.C. § 106(2), which protects derivative works.” After grossly mischaracterizing Campbell (which held that “[t]he central purpose” of the first factor inquiry is to determine “to what extent the new work is ‘transformative’”) and ignoring twenty years of post-Campbell case law, the 7th Circuit then fabricated a completely new market-driven test for fair use cases. First, the Court decreed that “[w]e think it best to stick with the statutory list, of which the most important [factor] usually is the fourth (market effect).” The Court then asked “whether the contested use is a complement to the protected work (allowed) rather than a substitute for it (prohibited).” Ironically, the court not only failed to identify any “statutory language” supporting the new test, but also cited to two previous 7th Circuit decisions (both authored by Judge Posner) which essentially say the exact opposite. See Chicago Bd. of Educ. v. Substance, Inc., 354 F.3d 624, 629 (7th Cir. 2003) (“fair use defense defies codification”).

As Prof. Matthew Sag astutely observed, “[t]hese are smart judges who could have helped further develop and clarify the law, but chose not to.” At least they affirmed the fair use finding.

10. October 17 – Cambridge Univ. Press v. Patton, 769 F.3d 1232 (11th Cir. 2014)

In the lengthiest fair use opinion of the year (by far), the 11th Circuit fielded a copyright infringement lawsuit brought by several publishing houses against officials of Georgia State University (GSU) concerning a university-wide policy allowing GSU faculty to digitally copy excerpts of the publishers’ works and make them available to students without paying the publishers. The publishers alleged 74 instances of infringement. GSU defended on fair use grounds.

The district court analyzed each of the allegedly infringing works individually, and in each instance, mathematically tallied (rather than balanced) the four factors. It also applied a blanket rule for determining the third factor whereby copying less than 10 percent of any work created a “safe harbor.” It ultimately found only five uses infringed. The appellate court reversed and remanded finding (among many other things) that although the district court took the appropriate approach in analyzing each work individually, it failed to apply the fair use test correctly for at least two reasons.

First, the appellate court held that any blanket rule creating a “substantive safe harbor” was improper. (The court also criticized the “Classroom Guidelines” found in the legislative history—and law professors everywhere rejoiced!) The appellate court said the district court should have analyzed the amount the GSU faculty took in light of the educational purposes and threat of market substitution.

Second, the appellate court held that the district court didn’t give enough weight to the fourth factor. Since the appellate court found that GSU’s uses were nontransformative because they fulfilled the same educational purposes as the original works, there was a greater threat of market substitution than the district court accounted for.

The concurring judge felt that the case could be decided based on one, all-important fact: GSU admitted that it paid the publishers a fee (and had done so for years) whenever its faculty used the exact same excerpts of copyrighted works to create paper coursepacks and only moved to digital coursepacks to save money on licensing fees. Thankfully, the majority correctly rejected this view in a footnote, finding that previous payments are irrelevant since “[a] number of factors might influence GSU’s decision whether to pay for permission, or instead, claim fair use.”

We’ll undoubtedly see this footnote text cited again sometime soon.