Fictional Software Brand In ‘Dark Knight Rises’ Movie Doesn’t Infringe Real-Life Software Brand–Fortres Grand v. Warner Bros.

This case involves a key plot device, called “Clean Slate” software, from the movie Dark Knight Rises, part of the umpteenth attempt to reboot the Batman franchise. The fictional software provides an uber right-to-be-forgotten; it “enables an individual to erase all traces of her criminal past from every database on earth so that she may lead a normal life.” (As an aside, this plot device illustrates how the Right to Be Forgotten naturally fits into a dystopian vision of the future). The “anti-hero” Catwoman eventually uses Clean Slate to overcome her shady past and, as an added bonus (?), apparently get frisky with Batman. In addition to the movie’s references to Clean Slate, there were fictional websites referencing Clean Slate that supported the movie’s marketing.

This case involves a key plot device, called “Clean Slate” software, from the movie Dark Knight Rises, part of the umpteenth attempt to reboot the Batman franchise. The fictional software provides an uber right-to-be-forgotten; it “enables an individual to erase all traces of her criminal past from every database on earth so that she may lead a normal life.” (As an aside, this plot device illustrates how the Right to Be Forgotten naturally fits into a dystopian vision of the future). The “anti-hero” Catwoman eventually uses Clean Slate to overcome her shady past and, as an added bonus (?), apparently get frisky with Batman. In addition to the movie’s references to Clean Slate, there were fictional websites referencing Clean Slate that supported the movie’s marketing.

The plaintiff markets a real-world software program called “Clean Slate,” which is “used to protect public access computers by scouring the computer drive back to its original configuration upon reboot.” The plaintiff alleges that its sales plummeted after the movie’s release, and it blames reverse trademark confusion, i.e., “potential customers mistakenly believing that its Clean Slate software is illicit or phony on account of Warner Bros.’ use of the name.” (Given the frenzied consumer demand for a right to be forgotten, this seems entirely not credible).

The court’s doctrinal analysis is borderline disastrous. That’s not unusual for reverse confusion cases, which ordinarily require a fair number of cognitive leaps-of-faith by judges. For example, the court discusses at some length what products it should be comparing. The court ultimately decides to compare the plaintiff’s software with the defendant’s movie, but the court says it “is also plausible that entertainment-based products could be confused as being affiliated with (by means of licensing) the same source as a movie.” Nevertheless, the court says “the only products available to compare—Fortres Grand’s software and Warner Bros.’ movie—are quite dissimilar, even considering common merchandising practice.” The court also says the allegation that consumers thought the software was illicit sounds more like a dilution harm, but the plaintiff’s trademark almost certainly lacked the requisite fame.

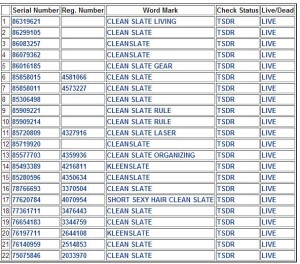

To me, the problem starts with the plaintiff’s crummy trademark, “Clean slate,” a common phrase that means “an opportunity to start over without prejudice.” Not surprisingly, I found 22 live registrations using the phrase:

Were all of these potential plaintiffs? I wonder if Warner Bros. did a trademark clearance before green-lighting the software name.

The movie uses the term in a completely descriptive manner. The most obvious doctrinal solution would be descriptive fair use. Unfortunately, the court treated the plaintiff’s trademark as suggestive, negating the defense. Treating the brand as suggestive also bypasses a palpable secondary meaning issue. These deficiencies demonstrate how current trademark doctrine can let a case involving the fictional reference to a dictionary term cause so much trouble. Rebecca gets into this some more.

I thought the court got to the real point when it said:

general confusion “in the air” is not actionable.

Far too frequently, a trademark plaintiff feels entitled to win based solely on two facts: the defendant “copied” its mark + some financial loss/windfall. In this case, the court summarizes: “Fortres Grand also argues that its drop in sales means there must have been confusion.” I love this stark statement because it highlights an obvious correlation vs. causation problem. Even if a loss in sales synced timing-wise with the movie’s release, that doesn’t prove causation–and it definitely doesn’t prove the existence of consumer harms recognized by trademark law. Trying to extract a lawsuit from such a correlation isn’t just a bad trademark case; I think it’s an abuse. The court speculated that the plaintiff’s sales decrease might be caused by lower visibility in search engine results (the movie’s references apparently pushed the software website down in search results), but this isn’t proved either.

This case also reminded me of similar cases over movie depictions of trademarked items, such as Caterpillar’s lawsuit against Disney for depicting a yellow earth-mover in George of the Jungle 2 or Wham-O’s lawsuit over Dickie Robert’s depiction of a slip-and-slide being misused. All of these lawsuits over trademarked products in movies are completely ridiculous, but trademark law lacks robust enough limiting principles to keep these cases from being brought.

Case citation: Fortres Grand Corp. v. Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc., 2014 WL 3953972 (7th Cir. Aug. 14, 2014)