Understanding the CCB’s First Two Final Determinations (Guest Blog Post–Part 3 of 3)

By guest blogger Elizabeth Townsend Gard, John E. Koerner Endowed Professor of Law, Tulane University Law School

[See part 1 about defendant opt-outs and part 2 about defendant defaults.]

Eight months after filing, the first two Copyright Claims Board (CCB) Final Determinations have been handed down. Flores v. Mitrakos, 22-CCB-0035, February 15, 2023, and Oppenheimer v. Prutton, 22-CCB-0045, February 28, 2023.

The Copyright Claims Board allows claimants to file copyright dispute claims for five situations: alleged copyright infringement; a declaration of noninfringement of an exclusive right; claim for misrepresentation during the notice and counter-notice process under the DMCA; counterclaims; and all “legal or equitable defenses under copyright law or otherwise available.”

The process is as follows:

- Step One: A claimant starts a claim (infringement, noninfringement or misrepresentation), and pays the first part of the filing fee, $40.

- Step Two: The CCB does a compliance review of the filed claim to determine if the claim qualifies for the CCB. This is done by a staff attorney. If the claim is rejected at this stage, the claimant has opportunities to amend a claim twice.

- Step Three: If the claim is found compliant, the next step is service of process on the respondent, which is the claimant’s responsibility.

- Step Four: after being served, the respondent has sixty days to opt out.

- Step Five: if the respondent does not opt out, then the claim enters the “active phase.” The respondent files a response to the claim. There is an Initial Order, where the claimant pays the second part of the filing fee, this time $60.

- Step Six: 14 days after the Initial Order and payment of the second fee, the CCB issues a Scheduling Order, which includes a timeline for the respondent’s response, pre-discovery conference, discovery, post-discovery conference, written position statements, a hearing, and determination. The claimant must also, if they have not already, register their work under the expedited system for the CCB.

Flores and Oppenheimer are the first two claims to reach a Final Determination. (Others have dropped out because they did not pass the compliance review, the respondent opted out, or for other reasons). These first two final determinations provide a glimpse into the process that is occurring, and how the Board is making its decisions. Let’s take a look.

Flores v. Mitrakos

The first determination to be handed down was Flores v. Mitrakos. Unlike most of the CCB cases to date, this case involves Section 512(f), the DMCA cause of action for bogus takedown notices. Consistent with the CCB’s small claims court ethos, the case involved both a pro se claimant and respondent. The outcome itself was stipulated by the parties, deferring most of the interesting questions about the CCB to future rulings.

Michael Flores, representing himself, filed a claim for misrepresentation under Section 512(f) on June 28, 2022, twelve days after the CCB began. He alleged that Michael Mitrakos had filed a false DMCA takedown notice with Google. He included the full notification of the take-down in the form. Flores sent a DMCA 512(g) counter-notice on June 27, 2022, and filed with the CCB the next day. He explains: “My use of facts was from a database that originally was partially under my copyright authorship and published online and viewable via the content taken down since 2021, and the database was then used with written permission to populate the one viewable from the content as it was when taken down.” Essentially, a working relationship has gone sour.

Here is the description of the misrepresentation:

I have a database of “facts” and handpicked images for hundreds of locations around the world. This extension stole all of that data, every single one of my images and every single “fact” letter for letter.” Respondent claims he is the “owner” of this “factual” data, and that the images he is also the owner of. In fact, the factual data was scraped by both of us over a period of time in 2021 and 2022 and put into a database. When we determined that we should end our working relationship, I asserted my authorship claim over the content being taken down, and in writing he said “I give you permission to take the API codebase to recreate heroku” (Heroku is a provider of database and other services). I proceeded to do that. Now here he claims this infringed his copyright, when in fact this is merely a retaliatory claim due to my filing a DMCA claim based on his appropriation of my design and copyright computer code expressions on multiple occasions without written or verbal permission.

Flores claimed the harm suffered is income from the site.

Notice of Compliance and Directions to Serve: August 3, 2022

The CCB provided Michael Flores with a Notice of Compliance and Direction to Serve. (Less than half of CCB cases have reached that stage). The CCB Board found his complaint met “statutory and regulatory requirements for bringing a claim,” and that the claim “provided enough information” for respondent to respond to the claim. The document then directed Flores to serve in a “Service Packet,” provided by the CCB in a PDF, and upload proof of service to the CCB within 90 days of notice. The Service packet includes:

- An initial notice

- The approved claim, along with any supplemental documents submitted with your claim

- An opt-out notification form.

Flores was to print out the Service Packet, staple it (yes, they include that step), and have it served to each respondent. This is the first physical element of the process. Then, Flores had to upload the Proof of Service to the eCCB within seven days of completing service.

If service didn’t happen within 90 days of this notice, the claim would be dismissed without prejudice. The Proof of Waiver was uploaded by Michael Flores, but it is locked.

Opt-Out Period

Once notice is waived or served, a 60-day opt-out period began for the Respondent. The respondent did not opt out and the opt out period ended on October 24, 2022.

The “Active Phase” – October 24, 2022

Once the waiver had been uploaded, the case entered the “active phase” because the respondent completed a waiver of service form and did not opt out within the sixty day period.

Flores selected the “smaller claims” track, which is more streamlined, with only one presiding Copyright Claims Officer.

First Default Notice

The respondent had until December 27, 2022 to file a response. The respondent did not respond then, and the CCB sent a notice on January 11, 2023. Six days later, on June 17, 2023, the Respondent filed a response:

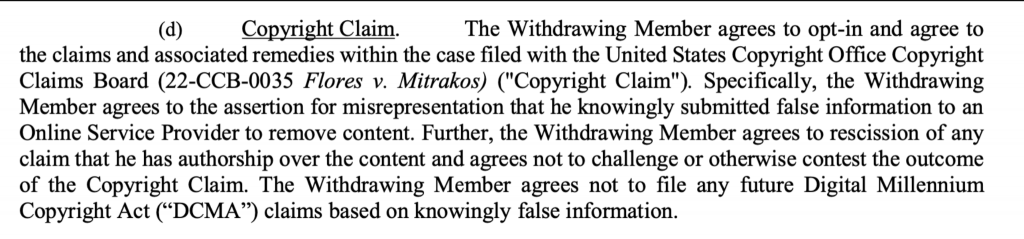

In other words, the respondent acquiesced to the complainant’s requests. At an initial conference on January 23, 2023, the parties reached a settlement and asked to dismiss the claim. On February 3, they submitted a joint request to dismiss the proceeding:

However, it is not what I expected for the first case to be finally determined: Section 512(f) and an ownership dispute between former business partners. And the Copyright Claims Officer did not make a substantive determination; the case was merely settled.

To recap:

- Event occurred (notice-and-takedown sent by Respondent): June 27, 2022

- Counter notice by Claimant sent: June 27, 2022

- Claimant filed CCB Misrepresentation claim: June 28, 2022

- A month later: Respondent is requested to create an eCCB account July 25, 2022

- Notice of Compliance and Direction to Service Notice (including Opt-Out Option to Respondent) – August 3, 2022

- Proof of Waiver uploaded on August 16, 2022

- Opt-out Period expires and Order to Pay Second Filing Fee and Register for eCCB (registering the work) – October 24, 2022

- Claimant pays the secondary filing fee the same day.

- Initial Scheduling Order – October 26, 2022

- The respondent does not respond – First Default Notice Jan 11, 2023

- Claim Response by Respondent, January 17, 2023 (he concedes)

- Initial Conference on January 23, 2023 where parties agree they had reached a settlement and wished to dismiss.

- Request for Dismissal by both Parties, February 3, 2023

- Final Determination Feb 15, 2023.

Eric asked me: how would this have been different if the claimant had pursued the traditional route of suing in federal court? The CCB filing cost is about $300 less than federal court. The CCB costs only $40 to initially file, and $100 total if the respondent does not opt out. Second, the CCB has been designed to be streamlined and helpful to the pro se applicant. They fill in a form, rather than draft a complaint. The CCB also seems to provide an easy alternative to the next steps in a Section 512 issue, which was what happened in this case. And perhaps, the CCB is a less intimidating venue — these are really small claims, and this one even self-identified as a smaller claim. It made me think of a new opportunity: maybe one day we will have a “Judge Judy” show for the CCB claims! We will have to wait and see!

Oppenheimer v. Prutton

The second final determination was handed down on February 28, 2023. This claim was brought by a photographer–the population we thought would be using the CCB. But it was not a claim filed by Oppenheimer, but a claim referred to the CCB from the United States District Court for the Northern District of California. What? Yep.

§1509. Relationship to other district court actions

(a) Stay of District Court Proceedings.-Subject to section 1507(b), a district court of the United States shall issue a stay of proceedings or such other relief as the court determines appropriate with respect to any claim brought before the court that is already the subject of a pending or active proceeding before the Copyright Claims Board.

(b) Alternative Dispute Resolution Process.-A proceeding before the Copyright Claims Board under this chapter shall qualify as an alternative dispute resolution process under section 651 of title 28 for purposes of referral of eligible cases by district courts of the United States upon the consent of the parties.

Here’s the odd part. The stay was issued on April 6, 2022 — over two months before the CCB became active. So, let’s go back to the original complaint Oppenheimer filed in federal court.

On February 25, 2021, David Oppenheimer filed a complaint against Douglas Prutton. At issue was one photograph of the Ronald V. Dellums Federal Building in Oakland, California. Oppenheimer had made the photograph available on his website, http://performanceimpressions.com. He appears to take aerial photographs of many different cities. The picture at issue was taken in 2017, and was registered with the U.S. Copyright Office on July 29, 2017. Here is a screenshot of his page, including apparently the photo in question:

Douglas Prutton appears to be a solo practitioner practicing in the Bay Area. In 2019, he had a simple website that included a “Where We Work” page. As part of that page, he had images of buildings; one of them included Oppenheimer’s image. Note: this is not on the front page of Prutton’s website, and looks like a typical web page, where someone made it for him, grabbed some images, and stuck them in. Screengrabs from October 29, 2019 from the Wayback Machine.

On June 4, 2018, Oppenheimer found his image on Prutton’s website. Prutton admitted to copying and said that his adult daughter had helped him with his website. (A typical thing that happens in our world). Oppenheimer sent him a letter. Prutton removed the image from his website. By November 21, 2019, the image is no longer included in the Wayback archive of that page.

Oppenheimer sued two years later, alleging infringement and removal of copyright management information. The case proceeds along in federal court. On April 16, 2021, Prutton responded. The case then is scheduled for mediation, which does not seem to go well. The case is scheduled for trial for May 2022. Then, on April 6, 2022, an order granting a stay of action until the matter is resolved before the CCB is issued. “The parties must file a joint status statement within one year of this order or within 14 days after a final decision by the Copyright Claims Board, whichever occurs earliest.”

So, they moved the dispute to the CCB venue, once it was open for business, instead of going to trial. Both agreed to this move, and as part of that, dropped the removal of copyright information claim. The Final Determination notes that Oppenheimer feels entitled to a licensing fee, even though he has not sold this photograph, and suggests that he is entitled to $2,775 a year for the use of the photograph.

So, they started the CCB process. It took 13 steps/documents to complete. Here are some highlights.

- The claim was filed on July 2, 2022. The claim says hat infringement is ongoing from 2018-present, even though the photo was removed in 2019. Claimant attached the original complaint, the order granting a stay, and exhibits.

- Scheduling Order, including facts that a Scheduling conference was held and that respondent waived their right to opt out.

- Prutton files an Answer, which appears to be his answer from the court case, as well as a Declaration of Respondent. Pruttton appeared pro se, even though he is an attorney himself. His “Declaration of respondent” says: “In 2019 I received a letter from a lawyer in Arkansas advising me that the photo of the Oakland courthouse on my website was his client’s photo (his client was David Oppenheimer). I responded with a letter telling this lawyer that I was sorry for the error and that the photo had been removed from my website. He responded with a letter to me demanding $30.000.00. I responded with an offer of $200.00. He responded by refusing to go below $30,000.00. I then offered $500.00. Mr. Oppenheimer then, through a lawyer in California, sued me in federal court.”

- We also get the declaration of his daughter, Mariana Prutton, who is a licensed marriage and therapy counselor in California. “Several years ago I offered to help my father with his business website. He agreed and I made some changes to his website. As part of those changes I believe I may have downloaded a photo of the federal courthouse in Oakland, California and put it on his website. I do not recall where I located the photo on the internet. I do know that the photo I downloaded from the internet of the federal courthouse did not have any copyright information visible on the image. There were many photos of that courthouse on the internet that did not have any copyright information on them. I would not have selected one that had such information on it. There would have been no reason to. I also did not crop the image so that any copyright information could not be seen. I would not have removed any copyright information as I do not even know how to do that. I do not even know if that is possible.” This was a declaration for the CCB Case, dated 1/10/2023.

- We get a little more information from Douglas Prutton’s statement of facts, including how Oppenheimer finds his photographs and litigates, and also that the trial date was set for May 2022: “The federal case was scheduled for trial on May 16, 2022. I served a subpoena on Mr. Oppenheimer’s attorney on March 29, 2022 demanding that Mr. Oppenheimer produce at trial documents regarding his income sources (from selling and licensing photographs and from copyright trolling). The next day, March 30, 2022. Mr. Oppenheimer’s attorney emailed me suggesting that we agree to present the claim to the copyright claims board in lieu of trial. and that the DMCA claim and attorney’s fee claims would be dropped, leaving only the copyright infringement claim.”

There’s a bit of mud throwing, e.g., Prutton calls Oppenheimer a “troll”. The CCB in the Final Determination sidesteps that issue, and looks to Prutton’s two defenses: fair use and unclean hands.

Fair Use:

From my perspective, the fair use analysis is what I’ve been waiting for. How is the CCB Board going to conduct a fair use analysis, and are they going to look at the precedent of the district court in which the case originally arose, in this case the 9tth circuit? As part of the law, that is what they are supposed to do.

The citations for the basics of fair use do come from 9th circuit cases. They note that Prutton did not address the first three factors: “Because the proponent of the affirmative defense of fair use has the burden of proof on the issue, Dr. Seuss Enters., L.P. v. ComicMix LLC, 983 F.3d 443, 459 (9th Cir. 2020), cert. den., 141 S. Ct. 2803 (2021), his failure to address three of the four factors is fatal to that defense.”

It’s worth reiterating that this is a pro se respondent, albeit an attorney, so the failure to address legal factors might warrant some grace. However, the fair use question has been addressed throughout the process of the district court decision, and the fourth factor was what the court and conversation was focused upon. The Final Determination did not include their previous conversation in this case about fair use, and instead, merely said that the respondent had not addressed the four factors.

The Board continues: “Moreover, based on the evidence in the record, the Board cannot conclude that any of those three factors weighs in favor of fair use.” They actually do a fair use analysis, factor by factor, using 9th circuit cases.

First, Prutton’s website promoting his law firm is commercial in nature and the use was non-transformative. Second, Oppenheimer’s photograph was creative. Third, Prutton uses the whole image. The fourth factor, impact on the market place, was addressed by Prutton, with the defense that Oppenheimer never licensed the photograph. It is worth quoting the Final Determination:

It is true that if Oppenheimer has not actually licensed the Work—and he has not come forward with any evidence to suggest that he has licensed of any of his photographs—any market effect caused by Prutton’s use of the Work may be minimal. However, that does not mean that this factor weighs in Prutton’s favor in this case. While not identifying any specific licenses for any of his photos in the past, Oppenheimer does state that he makes his photographs available for license on a public website and that this Work was likewise available. Oppenheimer Decl. ¶ 4 & Ex. C. Other cases where Oppenheimer has been a litigant show that he has some licensing history, however minimal. See Scarafile, 2022 WL 2704875, at *4 (suggesting Oppenheimer made “less than $5,000” from licensing his works in 2017). Therefore, there is a market available for this Work, which Prutton evaded by copying and displaying the Work on his website without permission. Because Prutton’s use of the work was commercial and “amount[ed] to mere duplication of the entirety of” the work, cognizable market harm is presumed to exist. Brammer v. Violent Hues Prods., LLC, 922 F.3d 255, 268 (4th Cir. 2019) (citing Campbell, 510 U.S. at 591); Leadsinger, Inc. v. BMG Music Publ’g, 512 F.3d 522, 531 (9th Cir. 2008). Furthermore, even if Oppenheimer had decided not to license the Work at all, he has the right to make that decision rather than see his works used without permission. See Harper & Row, Publrs. v. Nation Enters., 471 U.S. 539, 551 (1985).

Some takeaways:

- Respondent did not do a fair use analysis, but the Board did anyway.

- The Board used the cases from the relevant circuit, in this case the 9th Circuit.

- Using someone’s photograph on a commercial website (even buried on the “about us” page) does not constitute fair use because it is not transformative and uses the whole photograph. Tell your adult daughter this immediately!

- And the Board did not engage or acknowledge the already ongoing broader social or jurisprudential discussions about fair use in this case.

It makes me think of all of those images being used on websites across the Internet. This Final Determination really opens up the market for photographers to file CCB claims for uses.

Unclean Hands: The second defense is unclean hands. Prutton claims that Oppenheimer was unreasonable in settlement negotiations. We learn that Prutton offered $500 to settle, but the attorney insisted on $30,000. Also, Oppenheimer took Prutton to federal court over an incidental use of a photograph, which when asked was taken down two years before the complaint was filed in federal court. Prutton also brings up the allegation that Oppenheimer has a long history of pursuing copyright litigation suits.

The CCB turns to the 9th circuit again for the definition of “unclean hands,” including that it is rarely recognized. “Prutton does not present any evidence of actions taken in this case that would lead to the rarely-recognized finding of unclean hands.”

Damages. The Board then turns to damages. Remember, this case has been going since 2021. One can only imagine the legal fees and costs to this point. Oppenheimer requests the maximum statutory damages under the CCB of $15,000, since it was timely registered. (The Final Determination notes that the damages are $7,500 for not timely registered works). The Board then confirms it is timely registered. But then: “The issue is moot, however, given that the Board would not award over $7,500 in this case regardless of the cap.”

The Board addresses the Innocent Infringer Defense. The Board notes that for infringement the typical minimum award is $750. This is part of the Copyright Act, not CCB regulations. 17 U.S.C. Section 504(c)(1). Prutton wants the Board to apply the Innocent Infringer Defense, which lowers the minimum award to $200. 17 U.S.C. Section 504(c)(2) says: “in a court’s discretion where the infringer “sustains the burden of proving, and the court finds, that such infringer was not aware and had no reason to believe that his or her acts constituted an infringement of copyright.” What is the burden? His daughter submitted a declaration that she found no copyright notice on the image.

The Board responds: “Nothing in the Board’s mandate under 17 U.S.C. § 1504 would prohibit awarding as little as $200, should a respondent satisfy the burden of proof under the innocent infringer standard.” That is really interesting. Are they including that information in their handbook to help respondents with their defenses? Let’s look!

The Handbook provides a table of common defenses.

I don’t find anywhere discussing damages, and certainly not Innocent Infringer Defense. Yet, the burden is on the respondent to prove those elements. Moreover, the Innocent Infringement Defense is limited to copyright notice on a work, and removal of that notice is even worse. 17 U.S.C. Section 401(d). “Oppenheimer submits evidence that at least in some places where the Work is posted, there are full copyright notices.” So, did the Adult Daughter get it from a place where it had copyright notice or not? She says she did not remove it, and there was no copyright notice on the image she used. Wouldn’t one be able to tell from the original image uploaded at Go Daddy? This seems like a knowable fact.

The Final Determination continues: “However, in this case, the Board does not need to decide whether Prutton had access to copies of the Work with a copyright notice. The burden placed upon Prutton, an attorney, to prove that he “was unaware and had no reason to believe that his or her acts constituted an infringement of copyright” is clearly not satisfied here.” The Board does not explain why. We have no clear understanding of what the standard and requirement might be, and if this was a pro se respondent, apparently no guidance, at least in the CCB Handbook.

The Board does cite to a case that rejects the notion that an innocent infringement occurs when you find something on the Internet and think it is free to use. So, that’s something. The defense that “I found it on Google and thought it was ok to use” will not fly with the CCB.

So, we get to the award part of the Final Determination. This part is fascinating.

- The Board affirms that statutory damages do not have to correspond to actual damages, of which Oppenheimer had none.

- Courts have discretion as long as the award falls within the statutory range of $750 and in this case, $15,000 for timely registered works at the CCB.

- Courts generally look to the relationship of the actual damages and statutory damages, including the Northern District of California.

- Various courts have limited damages to $750 when a plaintiff has not submitted valid proof of actual damages, so as not to have a windfall.

Oppenheimer did not submit evidence that he licensed this work or any other works. The Board notes that Oppenheimer has been awarded $750 in at least two previous cases that are similar to this one. So, that’s interesting. First, that there is a record of Oppenheimer’s work, and second, that the Board reviewed the damages from previous cases. These are mentioned by Prutton in his responses to the CCB.

Also interesting: the three-panel Board voted…and included the vote in the Final Determination. Two members wanted to award $1,000, and one wanted to award $750. They settled on $1,000. “Prutton used a small image of the Work on a subpage of a website and there is no evidence that Oppenheimer suffered any damages or that Prutton reaped any gains from the use. However, Prutton’s use was commercial in nature and lasted at least a year. The Work is an aerial photograph, which arguably gives it extra value. The size of the image placed on his law firm website was not large, but it was clearly larger than thumbnail-sized. On balance, the damages awarded should exceed the minimum of the statutory range.”

This is amazing as well. The damages seem to be based on:

- Length of time on the website

- The size of the image

- The nature of the website (e.g. commercial, although there is not much deeper analysis of what makes a webpage commercial, and if an information page about the solo law firm constitutes a commercial use).

- The nature of the image: that it is an aerial photograph.

So, I’m not sure how satisfying this second Final Determination is. In some ways it is both hopeful and worrisome.

Hopeful:

- Careful analysis is being done, including using the appropriate cases from the jurisdiction at hand

- Even when a respondent doesn’t make a full fair use analysis, the Board does.

- The Board looked to previous outcomes of litigants to make sure there was no windfall.

- The Board is using the parameters of the Copyright Law for damages, which means we can rely on the case law to understand that.

Worrisome:

- Common behavior was penalized $1,000 plus years of litigation.

- When respondents do not make complete arguments, they are penalized. This is worrisome with pro se respondents.

- The Handbook doesn’t seem to help the parties understand the damages part of the analysis, which potentially includes Innocent Infringer.

- The CCB did not address the offer to settle for $500, and the claimant’s insistence of $30,000. There was no taking this into consideration. Ideally, the offer to settle should have been addressed.

So, that’s the second case. I was curious if Oppenheimer had filed other claims at the CCB. It appears, for the moment, this is the only one. It will be interesting to see if the outcome feels successful to a serial litigant or not.

But the Oppenheimer decision is much more troubling, once you realize that a good amount of the cases being filed are photographers complaining that a company — often small like the law firm — are casually using a photograph on a website. Will the CCB change our culture? When my kid was in the 4th grade — about a decade ago — the first assignment after the first day of school was to find Google images and put them on their binder. The CCB with this decision may signal that the era of grabbing images and pasting them on one’s website is over or it might cost $1,000. And with companies like Pixabay and others, that is so much easier to do. So CCB + search capabilities may change our relationship to how we think about images. We will see what happens.

[Commentary from Eric:

In the Oppenheimer case, I wonder if the CCB process was helpful to the parties compared to remaining in federal court. I think we could make an argument that the CCB resolved the dispute that had been festering in court, but we also have proof that the plaintiff in this case didn’t need the lower-cost access provided by the CCB because he proved he was willing to go to court. Maybe both parties would have been better off if the case had started in the CCB rather than in federal court.

As for the denouement, the $1k award surely isn’t that exciting to photographers. It’s vindication of the plaintiff’s claim, but photographers will have to spend $100 just to start, plus the cost of effectuating service, and then spend many months adjudicating it–all for a $1k payoff…? Is that a good use of photographers’ time and money? Perhaps the CCB won’t attract more photographer claims if $1k proves to be the prevailing damages award. Plus, since the photographer’s C&D got the defendant to stop the infringement by removing the photo, maybe society would have been better if no litigation took place at all?

If this case had remained in federal court, it’s not clear what the court would have done with the attorneys’ fees. Oppenheimer was nominally the prevailing party, but the damages award of $1,000 was much closer to Prutton’s $500 settlement offer than it was to Oppenheimer’s unreasonable demand of $30,000. For that reason, I think a court might have decided that PRUTTON was the prevailing party and made Oppenheimer pay his attorneys’ fees. The CCB has very limited rights to award attorneys’ fees, so perhaps Oppenheimer dodged that bullet.]

Conclusion

One case related to ownership and Section 512. The other related to what seems like a copyright owner who litigates on images that have no licensing income, coming from the district court. We’re still waiting for a basic infringement case – started as a claim, and with potentially a fair use defense. Let’s see what comes down next.

Prior Blog Posts on the CCB

- Copyright Claims Board (CCB) Default Notices (Guest Blog Post–Part 2 of 3)

- Copyright Claims Board (CCB) Opt-Outs – How’s That Going? (Guest Blog Post–Part 1 of 3)

- A 5 Month Check-In on the Copyright Claims Board (CCB)

- A 3 Month Check-In on the Copyright Claims Board (CCB)

- A First Look at Copyright Claims Board (CCB) Filings

- The Copyright Claims Board Is Opening Next Week. Are You Excited?

- A Glimmer of Hope That the Copyright Claims Board (CCB) Won’t Turn Into a Troll Factory

- Comments on the Copyright Office’s Copyright Claims Board Rulemaking

- A Summary of the Copyright Claims Board (CCB) [Excerpt from my Internet Law casebook]