Consumers Don’t Think Plant-Based “Milks” Are Cowmilk, But the FDA Wants More Disclosures Anyway

“The issue is, what is milk?”

The FDA uses the term “milk” to describe cowmilk [FN], but that isn’t a single commercial product from a nutritional standpoint–there are various versions of “milk” with different fat percentages, with lactose removed, and other modifications. (To make things even more complicated, the FDA now says some fortified soy-based “beverages” are nutritionally equivalent to cowmilk and thus covered by the FDA’s “dairy” recommendations).

[FN: The FDA expressly “does not address other types of mammalian milk, such as goat milk, sheep milk, and camel milk, that may be used as substitutes for milk. These types of milk are used far less frequently than plant-based milk alternatives as substitutes for milk and therefore do not pose the same potential public health concern.” Later, it says “At this time, FDA is not aware of a potential public health concern associated with substituting other mammalian milks for milk.” I guess it doesn’t care about the different nutritional profiles of alternative mammalian milks so long as there’s not a big economic lobbying group squawking about them?]

During the Trump administration, the FDA expressed concern that consumers were switching to plant-based milks because they thought it was a substitute for cowmilk. Predicated on that empirical assumption, and with a lot of encouragement from the dairy lobby, a number of states have banned plant-based milks from using the term “milk.” This is why you’ll sometimes see plant-based milks referred to as “beverages,” “drinks,” or other inferior synonyms.

To the FDA’s credit (and in contraposition to the states besieged by the dairy lobby), it actually studied consumer understanding of plant-based milks. Its conclusion is emphatic (emphasis added):

“milk” is strongly rooted in consumers’ vocabulary when describing and talking about plant-based milk alternatives. The focus groups indicated that most participants were not confused about plant-based milk alternatives containing milk and refer to plant-based milk alternatives as “milk.” Participants further indicated that they feel familiar and comfortable with the term “milk” when describing plant-based milk alternatives and they preferred to use the term when given a choice of names for plant-based milk alternatives (e.g., “milk,” “beverage,” “drink,” etc.). Participants also said that the term “beverage” and “drink” may suggest lower quality than a product called “milk”. Other research also appears to show that consumers understand that plant-based milk alternatives are distinct products and choose to purchase plant-based milk alternatives because they are not milk. For example, as noted above, some consumers purchase plant-based milk alternatives because of allergies, intolerances to milk, or lifestyle choices (e.g., vegan diet)

Later, the FDA says flatly: “consumers, generally, do not mistake plant-based milk alternatives for milk.”

This is a damning conclusion for the dairy lobby’s protectionist efforts and the legislators who prioritize the dairy lobby over their constituents. The FDA is saying that moving plant-based milks off of the term “milk” doesn’t improve consumer understanding. If anything, it potentially harms consumers by sending a signal of inferiority.

That doesn’t end the FDA’s inquiry. It then goes onto say: “consumers, including consumers who purchase plant-based milk alternatives, do not understand the nutritional differences between milk and plant-based milk alternatives.” This already exposes some of the FDA”s nomenclature troubles, because its baseline of a generic “milk” subsumes many different dairy products with different nutritional profiles.

The FDA continues (emphasis added):

a majority of consumers who purchase plant-based milk alternatives state they do so because they believe the products are healthier than milk. Additionally, in focus groups conducted by FDA with consumers of plant-based milk alternatives, frequent mentions were made that plant-based milk alternatives may be healthier than milk because they are lower in fat and cholesterol, and do not contain animal ingredients. Further, a survey reported that 53 percent of its respondents believe that plant based milk alternatives labeled with the term “milk” in their name have a nutritional content similar to milk. Another survey indicated that the term “milk” paired with “almond” creates a more favorable perception of the nutritional content of the product compared to “almond drink,” “almond beverage,” or “almond juice.” The survey data also indicated that its respondents expect that plant-based milk alternatives are comparable in nutrition to milk and this belief is stronger in those who purchase plant-based milk alternatives

The FDA is picking up that plant-based milk consumers may be trying to optimize different nutritional goals than cowmilk consumers. This isn’t good or bad; just different.

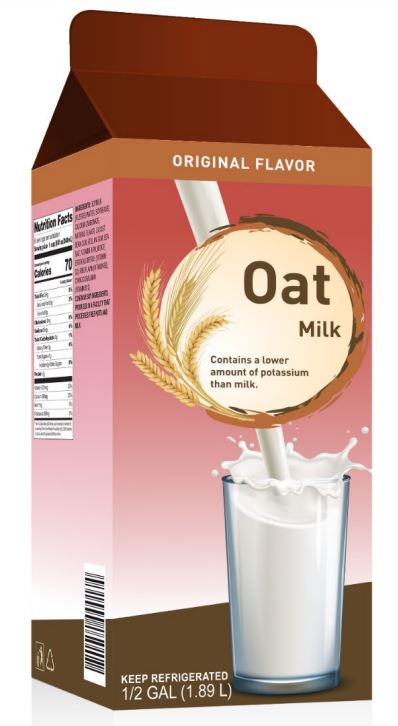

To address consumers’ understandings about the purported nutritional inadequacies, of plant-based milk, the FDA wants manufacturers to engage in voluntary corrective disclosures such as “Contains lower amounts of [nutrient name(s)] than milk,” which can be linked to the product name using a dagger footnote symbol. They even gave some representative images, though obviously not blessed by any plant-based milk marketing team:

Voluntary disclosures are fine, but why not in both directions? In other words, cowmilk manufacturers should disclose where their products are inferior to the plant-based milk options. The non-mutuality of the disclosure exposes the FDA’s residual bias: it still treats cowmilk as the baseline even though it’s an anachronism of a prior American diet/culture, one the FDA is sticking to despite the fact that Americans are already widely out of compliance with its recommended consumptions.

The FDA partially acknowledges this by permitting favorable comparative claims to cowmilk, but it still wants the purported deficiencies disclosed. Do you think consumers would find this mock-up less confusing than the status quo?

Instead of manufacturers’ disclosures, the FDA could do more to educate consumers about the relative pros-and-cons of cowmilk and plant-based milks. They have already started doing this (1, 2). But the FDA should more expressly address the limits of cowmilk–including the reasons why consumers might be switching away from cowmilk.

Related Posts: