Another Court Says Competitive Keyword Advertising Doesn’t Cause Confusion

This is a lawsuit between two Alzheimer’s-related non-profit organizations, the Alzheimer’s Association (the more established and better-funded group) and the Alzheimer’s Foundation (the relative upstart). I blogged a prior 2015 ruling.

The potential for brand collisions in consumers’ minds seems obvious. For example, “Between 2007 and 2012, Alzheimer’s Association received more than 5,700 checks made payable to “Alzheimer’s Foundation” or a variant totaling over $1.5 million…AFA, in turn, received more than 5,000 checks between 2006 and June 2016 made payable to “Alzheimer’s Association” or near variants.””

Both parties used competitive keyword advertising. The court describes the situation in some detail:

From June 2004 to the present, AFA has also purchased Association Marks as keywords. By late 2007, AFA was frequently purchasing “alzheimers association” and variants as search keywords. For part of this time – April 2012 to June 2014 – AFA ran sponsored ads that used the word “Association” in the text. After correspondence from the Association’s counsel, AFA discontinued the use of the word “Association” in the content of its ads, however AFA continues to purchase Association Marks as keywords and to advertise itself as “Alzheimer’s Foundation” in responsive ads.

The Association began its own keyword marketing program in April 2007. The Association spent approximately $150,000 annually on keyword advertising in 2015-16, but also utilized Google Grants for an additional $480,000 of keyword advertising. Initially, the Association purchased “Alzheimer’s Foundation” as a keyword, but all foundation-related keywords were removed from the Association’s SEM in August 2010. The Association did not believe it was acting improperly in purchasing foundation-related keywords….In August 2016, AFA’s trademark counsel wrote to the Association to complain that Alzheimer’s Association’s Northern California and Northern Nevada chapter had purchased “Alzheimer’s Foundation” as a keyword and displayed resulting advertising text with “Alzheimer’s Foundation” in the title. The chapter had recently merged with the Alzheimer’s Association, and upon receipt of the letter, the chapter discontinued purchase of the keyword.

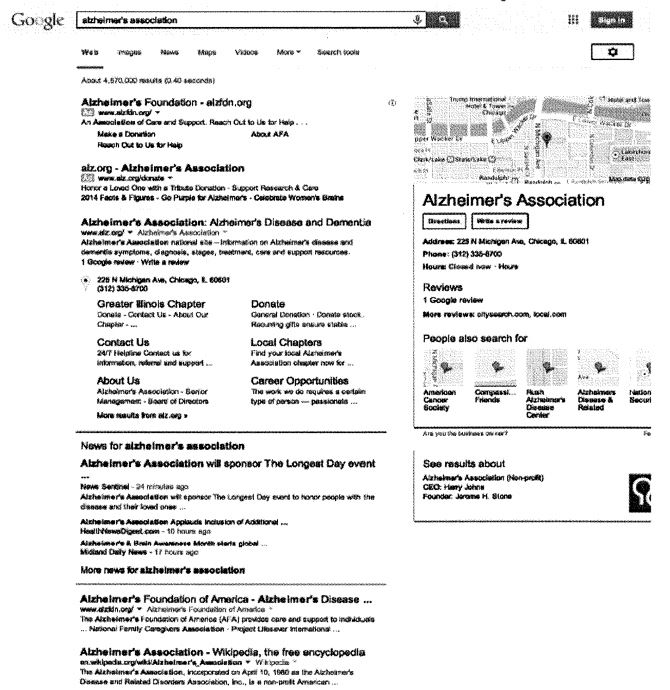

Presently, one of the at-issue ads run by AFA might show “Alzheimer’s Foundation” in the ad title, in standard typeface without any graphic element, followed by the associated website URL and a brief description or tagline. For example, as can be seen below, a Google search of “alzheimer’s association” from June 2014 shows AFA’s ad as the top result, with the main header as “Alzheimer’s Foundation – alzfdn.org” followed by a yellow marker reading “ad,” the URL “www.alzfdn.org” and a tagline of “An Association of Care and Support. Reach Out to Us for Help….” The advertisement also contains links to pages within AFA’s website for those looking to “Make a Donation,” to learn “About AFA,” or to “Reach Out to Us for Help.” Id. The second and only other ad result is from the Association. Their header reads “alz.org – Alzheimer’s Association,” is also followed by the yellow “ad” marker and the URL for their donation page, “www.alz.org/donate.” The Association’s tagline was “Honor a Loved One with a Tribute Donation – Support Research & Care” and included links to subtopics on their website…. [the court included the following screenshot, showing the foundation and association ads at the page top, plus many organic links for the association]

Purchasing keywords such as “Alzheimer’s Association” was part of the AFA’s so-called competitors campaign. In October 2011, Chris Leone, AFA’s SEO consultant, recommended increasing the daily budget for the competitor’s campaign, and AFA agreed. At times, the keyword “Alzheimer’s Association” received more clicks on AFA’s sponsored ad than those received from its own brand. In early 2012, Mr. Leone reported that campaigns targeting AFA’s competitors performed the best. The competitors campaign comprised roughly 40% of AFA’s keyword marketing budget. AFA also worked with a vendor named Vizions on an SEO plan involving keywords such as “alzheimers association,” but there is no specific evidence in the record that AFA adopted Vizions’ recommendations….

At trial, Mr. Leone opined that the “common strategy” of competitor-targeted ads was effective here because “Alzheimer’s Association is the larger organization” and “if someone is searching for Alzheimer’s Association, which they are frequently, then we’re providing a[n] ad as another option for them. It is the same thing that most competitors do.”…

In order to make an online donation to AFA, a consumer could not simply enter a keyword or click on an online ad, but would have to visit AFA’s website. If after looking at AFA’s website, a computer user determines that AFA is not the entity to which she wants to donate, the user can click back to return to her original screen page. To continue on to the donation page, a user would have to click on “Donate” or “Support Us” within the AFA website. On the donation page, there are many references to “AFA” or “Alzheimer’s Foundation of America,” and no references to the Association or use of any the Association Marks. At no point while on the AFA website during the donation process would a consumer see any of the Association Marks. A similar multi-step process would be required to make an online donation to the Association….

It would strain credulity to deny that AFA has purchased Association Marks as keywords in part due to the Association’s size and presence and not only because of the descriptive nature of the words.

The association sought to prevent the foundation from buying the association’s trademarks as search engine keywords. The lawsuit has been ongoing since 2010 (with prior litigation going back to 2007). The court held a 6 day bench trial.

The Court Ruling

Use in Commerce. The court says keyword advertising constitutes a use in commerce, citing Rescuecom v. Google, CJ Products v. Snuggly Plushez, LBF Travel v. Fareportal, and Allied Interstate v. Kimmel & Silverman.

Initial Interest Confusion. The court says competitive keyword advertising, by itself, isn’t infringing: “Virtually no court has held that, on its own, a defendant’s purchase of a plaintiff’s mark as a keyword term is sufficient for liability.” Cites to: 1-800 Contacts v. Lens.com, General Steel v. Chumley (2013), and Hearts on Fire v. Blue Nile.

The court defines its conception of initial interest confusion:

because a user diverted to the wrong website can easily get “back on track,” the Second Circuit has also expected a plaintiff prove “intentional deception” to prevail in an initial interest confusion case in the internet context. [cite to the Second Circuit’s 2004 Savin case]

The task of distinguishing between situations that are and are not actionable as initial interest confusion may be best illustrated by two scenarios. The first is a pure bait and switch scenario, which is clearly actionable. For example, if AFA had purchased Association Marks as keywords and then advertised itself as “Alzheimer’s Association,” with nothing in its ad to distinguish itself from the Association aside from its URL, this would be a clear case of infringement. By contrast, comparison ads are not violations of the Lanham Act because it is clear to consumers that the plaintiff’s mark is only being used as a point of contrast. For example, if Pepsi were to purchase the keyword “Coca-Cola” and then publish an ad with the headline “Try Pepsi – It Is Better than Coca-Cola,” it would be the rare consumer confused by the source of the advertisement; The consumer searching for “Coca-Cola” may have been diverted, but she has not been confused or misled. The sine qua non of trademark infringement is consumer confusion caused by the infringing behavior, and behavior meant to harm a competitor does not necessarily entail infringement if a consumer is unlikely to be confused. For this reason, courts have repeatedly found that the purchase of a competitor’s marks as keywords alone, without additional behavior that confuses consumers, is not actionable. As one district court in Massachusetts framed the issue: “Mere diversion, without any hint of confusion, is not enough.” Court subscribes to that approach.

Thus, for the purpose of the Court’s analysis – which principally focuses on initial interest confusion – the crucial question is whether AFA’s actions in purchasing Association Marks as keywords and advertising itself under its two-word name are more akin to a bait-and-switch likely to confuse consumers, or to the simple act of offering consumers a choice.

Likelihood of Consumer Confusion. The court doesn’t evaluate initial interest confusion by itself. Instead, the court frames the issue: “Are AFA’s actions in purchasing Association Marks as keywords and advertising itself as ‘Alzheimer’s Foundation’ likely to cause consumer confusion?” and applies the standard Polaroid multi-factor likelihood of consumer confusion test.

- Mark Strength. “Alzheimer’s Association” is descriptive and conceptually and commercially weak. One survey only showed 11% of consumers mentioned the association when prompted to name organizations fighting Alzheimer’s. This factor weighs for the defense: “because of the weakness of the mark, it is not easy to disaggregate the consumers searching for the Association as a specific organization from those searching generically for an Alzheimer’s charity when they type “Alzheimer’s Association” or some similar derivation into a web browser.”

- Mark Similarity. Unlike some prior courts, this court doesn’t simply compare the trademark to the purchased keyword. “With respect to the Association’s claim regarding AFA’s purchase of Association Marks as keywords and metatags, the proper comparison is between the resulting ads for AFA and Association advertisements or other search results. This is how consumer confusion would manifest itself. The mere fact of AFA’s purchase of the Association Marks either verbatim, as with the keyword “alzheimer’s association,” or nearly verbatim, as with the keyword “alzheimer’s association memory walk,” cannot in and of itself cause confusion.” Still, the court says the factor weighs in favor of the plaintiff because the domain names and ad appearance are similar.

- Competitive Proximity. This factor favored the plaintiff.

- Bridging the Gap. This factor is irrelevant.

- Actual Confusion. The thousands of misdirected checks seem damning, but the court says they may reflect that the words “association” and “foundation” are synonyms. The court suggests “it is the weakness of the marks and consumers’ inattention, not AFA’s specific disputed practices, that yields confusion.” The court largely disregards the very, very expensive consumer surveys done by Dr. Van Liere.

- Bad Faith/Intent. The court concludes this factor weighs in favor of the defense, and that there’s no intentional deception.

- Product Quality. The court says this favors the plaintiff but gives the factor little weight.

- Consumer Sophistication. This factor favors the plaintiff because online consumers, even those who complete the multi-step process to make online donations, aren’t necessarily sophisticated.

Weighing the Factors. 4 factors favored the plaintiff, 3 the defendant, and 1 was neutral. The court then applies a variant of the Network Automation test to say that the most important factors are mark strength, mark similarity, and actual confusion, and 2 of these 3 factors “strongly” favor the defendant. Furthermore, consistent with Network Automation’s approach, the court notes that ad labeling reduces initial interest confusion.

The court then tries to distinguish different consumer segments (I did something similar in my 2005 article):

- consumers not confused by the foundation’s efforts, either because they were searching for the term “association” generically or because the SERP educated them about the organizations’ differences.

- consumers who click on the foundation’s ads mistakenly thinking it was related to the association, and thus are diverted by initial interest confusion. For folks who make donations while still confused after clicking around the foundation’s website, the court says they experience traditional point-of-sale confusion.

- consumers who click on the foundation’s ads because they are confused by considerations other than the association’s actions.

The court wishes the Van Liere survey had shown how many consumers were in each segment. The court ultimately concludes the plaintiff didn’t satisfy its burden:

Is it possible that some consumers searching specifically for the Alzheimer’s Association are diverted to AFA’s website because it drops “of America” from its ad text? Yes. However, as with any alleged trademark violation, plaintiffs must prove “a probability of confusion, not a mere possibility.” The extensive trial record does not support a finding of such a probability. That some confusion may result from the similarity between “Alzheimer’s Association” and “Alzheimer’s Foundation” is not sufficient to conclude that AFA’s actions are likely to mislead “an appreciable number of ordinarily prudent purchasers.”

The court also dismissed the metatag issues: “the Court finds that AFA’s metatag practices are largely immaterial to the present issue, as they have likely not been used by search engines since before 2009, and so have little effect on the ordinary prudent consumer. ”

Implications

Keyword Ads Don’t Confuse Consumers. For years, we’ve had growing evidence that consumers aren’t inherently confused about keyword advertising, including at least several defense wins at trial ( Fair Isaac v. Experian (2009) (technically, the final win came in a post-trial ruling after a jury trial); College Network v. Moore (jury ruling in 2009; affirmed on appeal in 2010); Consumerinfo v. One Techs. (2011) (jury trial); General Steel v. Chumley (bench trial)). This detailed and thoughtful opinion, the product of enormous financial investments in the lawsuit, should reinforce the long-prevailing view that competitive keyword ads don’t confuse consumers in a legally recognizable way.

What a Waste (Part 1): These two charitable organizations have been beating up on each other in court for over a decade. It’s hard to imagine how many millions of dollars have been siphoned away from helping the charitable cause and instead have been used to fund the lawyers’ children’s private school tuition. Surely these folks could find some way to collaborate for the common good rather than fighting over the spoils. But since they can’t, I cannot imagine any circumstance where I’d feel comfortable giving either organization my charitable dollars. As the court explained in 2015:

This case presents a unique set of circumstances where the public interest is harmed not by the conduct of one party or another, but by continuation of the litigation itself. The parties in this case are two legitimate and respected charities working to combat a cruel disease that robs its victims of their cognitive ability and sense of self.

Their work is both admirable and desperately needed, yet in this litigation they are spending immense financial resources in order to gain an entirely speculative edge in fundraising. This serves neither their constituencies’ interests nor that of the public at large.

But for the parties’ intransigence and inability to find common ground, resources expended on discovery, summary judgment motions, trial, and appeals would be directed toward providing care and support to people suffering from Alzheimer’s Disease, or toward research that might make progress on finding a cure.

What a Waste (Part 2): Competitive keyword advertising lawsuits are almost never a wise investment. If you’re a trademark owner thinking about suing over competitive keyword ads, I hope you’ll do some honest introspection about what you’re trying to achieve. Odds are strong that whatever your goals are, litigating over competitive keyword advertising isn’t likely to get you there.

Case citation: Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association, Inc. v. Alzheimer’s Foundation of America, Inc., 2018 WL 1918618 (S.D.N.Y. Apr. 20, 2018)