It’s Not Possible To Steal Facebook ‘Likes’–Mattocks v. BET

In 2008, Plaintiff Stacey Mattocks developed an (initially unofficial) Facebook page focusing on “The Game,” a television series initially aired on CW and later acquired by BET.

In 2010, BET contacted Mattocks and hired her as a part-time worker, paying her $30 per hour. Her duties included maintaining the aforementioned Facebook page. After BET hired Mattocks, it turned the Facebook page into an official one by displaying logos and trademarks, and it encouraged viewers to like the page. Mattocks was the main content contributor to the page, but other BET employees contributed on occasion as well. During the time Mattocks worked for BET, the Facebook page grew from 2 million to 6 million likes.

In 2010, BET contacted Mattocks and hired her as a part-time worker, paying her $30 per hour. Her duties included maintaining the aforementioned Facebook page. After BET hired Mattocks, it turned the Facebook page into an official one by displaying logos and trademarks, and it encouraged viewers to like the page. Mattocks was the main content contributor to the page, but other BET employees contributed on occasion as well. During the time Mattocks worked for BET, the Facebook page grew from 2 million to 6 million likes.

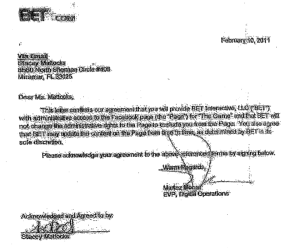

In February 2011, BET and Mattocks entered into a letter agreement. The agreement (pictured at right) did not contain very many terms. The court says “BET agreed not to exclude Mattocks from the page” and similarly Mattocks “granted BET administrative access” to the page. After signing the letter agreement, BET and Mattocks discussed full-time employment. In the course of their discussions, Mattocks restricted BET’s access to the page. BET in turn created a new page for the TV series and asked Facebook to “migrate” the fans from the existing page to the new page. BET also terminated the letter agreement. Facebook reviewed the original page, determined it “appeared to officially represent the brand owner” and, on this basis, granted BET’s request.  To add insult to injury, Facebook also shut down the original page. At BET’s request, Twitter also shut down the account Mattocks used to promote the series.

To add insult to injury, Facebook also shut down the original page. At BET’s request, Twitter also shut down the account Mattocks used to promote the series.

Mattocks sued for tortious interference, breach of the letter agreement, and conversion. The court tosses her claims on summary judgment.

Tortious interference: Mattocks claimed that BET improperly interfered with her contractual relationship with Twitter and Facebook. For interference with a contract to be unjustified under Florida law, the defendant must be a stranger to the business relationship. If the allegedly interfering party has an interest in the relationship, typically there’s no liability. BET has an interest in the Mattocks-FB and Mattocks-Twitter relationships, so it’s not a stranger. There’s an exception for interference that’s purely malicious or where improper methods are used. The court says there’s no evidence that BET’s intentions were purely malicious. Similarly, there’s no evidence of wrongful means. [We’ve blogged about wrongful takedowns of pages numerous times, and it appears BTE was relatively above-board on this score, but it’s interesting that Mattocks did not try to raise this argument.]

Breach of contract: The letter agreement unfortunately for Mattocks was sparse. Like, “back of the napkin” sparse. It contains two essential promises. The court says that Mattocks breached her promise by demoting BET’s access and thus excused BET’s performance under the letter agreement.

Mattocks additionally alleged that BET breached the covenant of good faith. Florida law (unlike California’s) isn’t terribly plaintiff-friendly on this issue. It requires a duty of good faith claim to be anchored to an express term of the contract. Unfortunately for Mattocks, there was no express term to anchor a good faith claim.

Conversion: Her final claim is for conversion because BET “converted a business interest she had in the FB page—namely the ‘likes’ that the page had accumulated while she worked on it.” The court says Mattocks has no property interest in “likes”. As the court explains:

‘liking’ a Facebook Page simply means that the user is expressing his or her enjoyment or approval of the content. At any time, moreover, the user is free to revoke the ‘like’ by clicking on an ‘unlike’ button. So if anyone can be deemed to own the ‘likes’ on a page, it is the individual users responsible for them. . . . Given the tenuous relationship between the ‘likes’ on a Facebook Page and the creator of the page, the ‘likes’ cannot be converted in the same manner as goodwill or other intangible business interests.

[If you listen closely, you can hear the sound of a million social media consultants weeping.]

Even assuming Mattocks has an ownership interest in the likes, the court says that all BET did was ask Facebook to migrate the page, and Facebook’s grant of BET’s request undermines any claim that BET used wrongful means.

__

Ugh. This case raises a smorgasbord of interesting internet law issues and does not resolve them in a very satisfactory way. Above all, it just reaffirms how difficult it is to translate social media assets into legal causes of action. I’m reminded of the Phone Dog case which feels very similar to this one. It’s interesting also that Bland v. Roberts, the Facebook like case from the Fourth Circuit, doesn’t help Mattocks. The court says when discussing Bland that a user “remains in control of his or her ‘like’ at all times and is free to ‘unlike’ the page or content by clicking an ‘unlike button provided by Facebook.” (See also Quigley Corp. v. Karkus: “Indeed, “friendships” on Facebook may be as fleeting as the flick of a delete button”.)

Ultimately, when viewing the letter agreement Mattocks signed, it’s tough not to feel that she was taken advantage of by the more sophisticated party (BET). For what appears to be zero dollars (and the slimmest possible legal consideration), BET essentially becomes a co-venturer of the obviously valuable page that Mattocks created. This is a terrible deal for Mattocks, and one that I can’t imagine she would have ever considered accepting if she had the benefit of hindsight.

But the case illustrates how difficult it is for the aggrieved contractor whose social media clout has been allegedly hijacked by a brand or an employer. Would employee social media legislation have helped Mattocks, especially after she became a part-time employee? Should it be of much use to someone in this situation? I’m inclined to say the answer is no on both of these counts, but as we’ve noted in numerous posts, employee social media legislation is not exactly the model of clarity.

One issue lurking in the background is the status of fan pages and their transitions into “official pages.” BET would (or should) have had a tough time forcing Facebook to take down a fan page or migrate its followers. However, after the letter agreement, BET seemed to encourage Mattocks to turn the page into an official page. This subsequently made it easier for BET to request Facebook to transition the fans over (a process I had little familiarity with). Given how BET’s encouragement made it easier for BET to take over the page’s value, some sort of implied misrepresentation claim may be lurking in the background here. Certainly, if the lawsuit had been brought in California, or another more plaintiff-friendly state, the chances for success would seem much higher.

Another thing to consider is what BET would have done if Mattocks initially offered to sell the page to BET. They would have probably unleashed their lawyers and threatened, perhaps speciously, an ACPA claim.

I’m full of sympathy for Mattocks. Maybe she can translate this episode into another gig in the social media space. In the meantime, her story serves as a warning as to the ephemeral and legally fluid nature of social media assets; and the fact that when it comes to third party platforms, we are all ultimately at their mercy. (Or, as Eric mentioned the other day, “All cloud services turn on their users eventually.”)

Additional coverage (& h/t): BET Wins Legal War Over Fan’s Facebook Page (Eriq Gardner)

Case citation: Mattocks v. Black Entertainment Television, 2014 WL 4101594 (S.D. Fl. Aug. 20. 2014)

Related posts:

Employee’s Claims Against Employer for Unauthorized Use of Social Media Accounts Move Forward–Maremont v. SF Design Group

Employee’s Twitter and Facebook Impersonation Claims Against Employer Move Forward — Maremont v. Fredman Design Group

Ex-Employee Converted Social Media/Website Passwords by Keeping Them From Her Employer–Ardis Health v. Nankivell

Washington State’s Proposed Employer Social Media Law: The Legislature Should Take a Cautious Approach — SB 5211

Ex-Employer’s Hijacking of a LinkedIn Account Is a Publicity Rights Violation–Eagle v. Morgan

Facebook Posts and Twitter Invites Don’t Violate Non-Solicitation Clause — Pre-Paid Legal v. Cahill

Battle Over LinkedIn Account Between Employer and Employee Largely Gutted–Eagle v. Morgan

Fight Over Access to Log-in Credentials for Blog Does not Trigger Copyright Preemption – Insynq v. Mann

Court Denies Kravitz’s Motion to Dismiss PhoneDog’s Amended Claims — PhoneDog v. Kravitz

Courts Says Employer’s Lawsuit Against Ex-Employee Over Retention and Use of Twitter Account can Proceed–PhoneDog v. Kravitz

An Update on PhoneDog v. Kravitz, the Employee Twitter Account Case

Pingback: Lazy Random Feed Time… | C y b e r L a w L a t e l y()