Appropriation Artist Can’t Win Fair Use Defense on Motion to Dismiss–Graham v. Prince

This is a lawsuit by plaintiff Donald Graham against well-known “appropriation artist” Richard Prince and his gallery for copyright infringement. As described by the court:

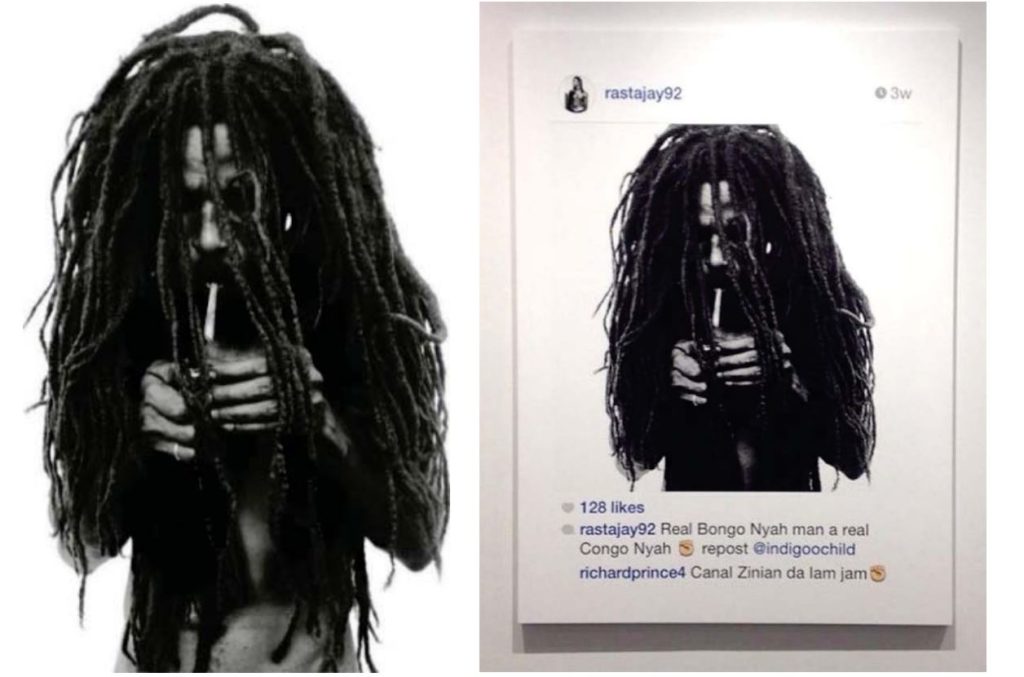

Prince’s [work] is [an . . . ] inkjet print of a screenshot taken by Prince that captures a ‘post’ made by a user named ‘rastajay92’ on . . . Instagram. . . Rastajay92’s post consists of a slightly cropped copy of [Graham’s photo] which he reproduced without Graham’s permission. In fact, rastajay92 had ‘reposted’ a copy of the photograph that had previously been posted by yet another Instagram user, ‘indigoochild.’ When rastajay92 reposted the image, he also commented: ‘Real Bongo Nyah man a real Congo Nyah [emoji of a raised fist].’ . . . Rastajay92’s comment also attributed his post to indigogoochild by stating: ‘repost @indigoochild’.

Prince added an Instagram comment of his own: ‘Canal Zinian da lam jam [emoji of a raised fist].’ He then screenshotted the post with his own comment, and printed the screenshot on canvas.

A comparison between Graham’s photo and Prince’s work is below:

Prince filed a motion to dismiss on fair use grounds. The court denies his request. The court says fair use cases are rarely adjudicated on the pleadings because fair use is a fact-intensive inquiry and requires development of the record. The court repeatedly (unfavorably) compares this case to a previous fair use case involving Prince (Cariou v. Prince), which he won largely on appeal in the Second Circuit.

The purpose and character of the use and whether it’s transformative: The court says this is the key factor. Applying an objective test, the court says the works in question are not so aesthetically different from the original that they would pass the “reasonable viewer” test as a matter of law. Prince tried to come up with a variety of messages sought to be conveyed by the work, including:

A commentary on the power of social media to broadly disseminate others’ work, an endorsement of social media’s ability to generate discussion of art, or a condemnation of the vanity of social media.

The court says the side-by-side comparison shows that the underlying work is not materially altered. There is some de minimis cropping, in the frame of an Instagram post, along with a cryptic comment . . . but otherwise, it’s . . . a screenshot.

Because the work is not very transformative, the commercial sub-factor is less significant.

Nature of the work: The second factor favored plaintiff because the works were published and creative. [Eric’s note: normally the work being published supports the fair use defense, but the court managed to turn that around.]

Amount and substantiality: The third factor focused on the extent of the work used. Given that Prince reproduced Graham’s photo in its entirety, the court says this factor can’t weigh in favor of Prince. Prince argued that he needed to copy the entire photo to effectively comment on it, but the court is not persuaded.

Effect on the market: The court says it does not have sufficient information at the pleadings stage to find that Prince’s use usurped the market for plaintiff’s work. Several of plaintiff’s allegations point to an overlap that the markets targeted by the two parties were the same and Prince’s work may serve as a substitute for Graham’s. Drawing the inferences in Graham’s favor, the court says this factor favors plaintiff.

The court declines to rule in favor of Prince. Graham also alleged a few other infringements, including reproduction of Prince’s work on a billboard and on Twitter (in a compilation format). The court says whether these uses are fair use present even tougher factual questions. The court also declines to convert the motion into one for summary judgment.

__

As the court notes, cases finding fair use at the motion to dismiss stage are rare. It would have been surprising for the court to conclude that Prince’s key contribution—adding a comment on a social media platform—would be sufficiently transformative to carry the day on fair use. Indeed, it would upend the copyright rules as they apply on social media platforms.

I’m intrigued by the decision by Prince’s lawyers to file a motion to dismiss. That seemed like a long shot here, but perhaps they were hoping the court would take the opportunity to convert the motion into one for summary judgment. (Eric offers additional comments on this issue.)

We haven’t seen a ton of cases raising infringement issues relating to users’ sharing of social media content. AFP v. Morel raised this issue slightly, and there the media defendants tried to rely on the argument that the Twitter terms of service allowed them to further distribute the content and exploit it but the court shut down that argument. Prince makes no such argument here. Eric raises a good point below about whether the result would be different if Graham had posted the photo to Instagram. I tend to think not, given that instagram’s terms of service, like twitter’s likely authorize reproduction “within the ecosystem,” but it’s an interesting question to consider.

__

Eric’s Comments

* Fair use on motions to dismiss. We’ve blogged other cases where courts did grant fair use defenses on motions to dismiss. See, e.g., Righthaven v. Realty One; Denison v. Larkin. However, the court is correct that such defense wins are rare. See, e.g., Katz v. Chevaldina, where the blogger won the fair use defense with a fee shift, but only after the motion to dismiss was denied. Therefore, Prince’s failure to win the fair use defense here isn’t very surprising. His fair use defense will get more traction on the summary judgment motion (though there are no guarantees of victory). However, to me, the adjudicatory costs of a fair use defense are one of its weaknesses. Prince may be able to afford the litigation costs, but many mom-and-pop content producers will fold long before the case can get to summary judgment or trial.

* The role of Instagram’s terms of service. As Venkat notes, the terms of service for social media services may contain broadly worded licenses that would protect the republication of screenshots. Here, the plaintiff didn’t consent to Instagram’s terms of service because a third party made the Instagram post without the photographer’s permission.

* Depicting screenshots of social media services. Prince created this legal tangle in part by adding his own nonsense comment to the Instagram post. Let’s assume he wasn’t doing this as an artistic statement but rather as an actual substantive comment to the post. Shouldn’t Prince have the legal right to share his comment in context? His comment doesn’t make sense even in context, but it would make even less sense out of the context of the other comment and the original photo. Our legal doctrines will need to accept the republication of user comments that include the surrounding comments and original source material.

* What is Appropriation Art? I must confess that I don’t “get” Richard Prince’s art. What makes it “art”? The fact that he declared it art and styles himself as an artist? I’m reminded of the examples where teenagers left eyeglasses on an art museum floor and visitors interpreted it as art; or vice versa.

* Emoji usage. I’ve added this opinion to my Emojis and the Law worksheet. As with the vast majority of cases, the court opinion doesn’t depict the emoji but instead textually characterizes it as the “raised fist.” The omission of the emoji image isn’t consequential to this case, but the court also could have easily included it in the opinion–which would have been a better practice because the emoji is part of the artwork (you can see it in the photo above).

Case citation: Graham v. Prince, 2017 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 111521 (SDNY July 18, 2017)

Related posts:

Blogger Can’t Defeat Copyright Infringement Claim on Motion to Dismiss–Katz v. Chevaldina

Copying Blogger’s Posts In Disciplinary Proceeding Is Fair Use–Denison v. Larkin

Blogger Wins Fair Use Defense…On a Motion to Dismiss!–Righthaven v. Realty One