Virtual Casino’s “Sign-in-Wrap” Formation Fails–Kuhk v. Playstudio

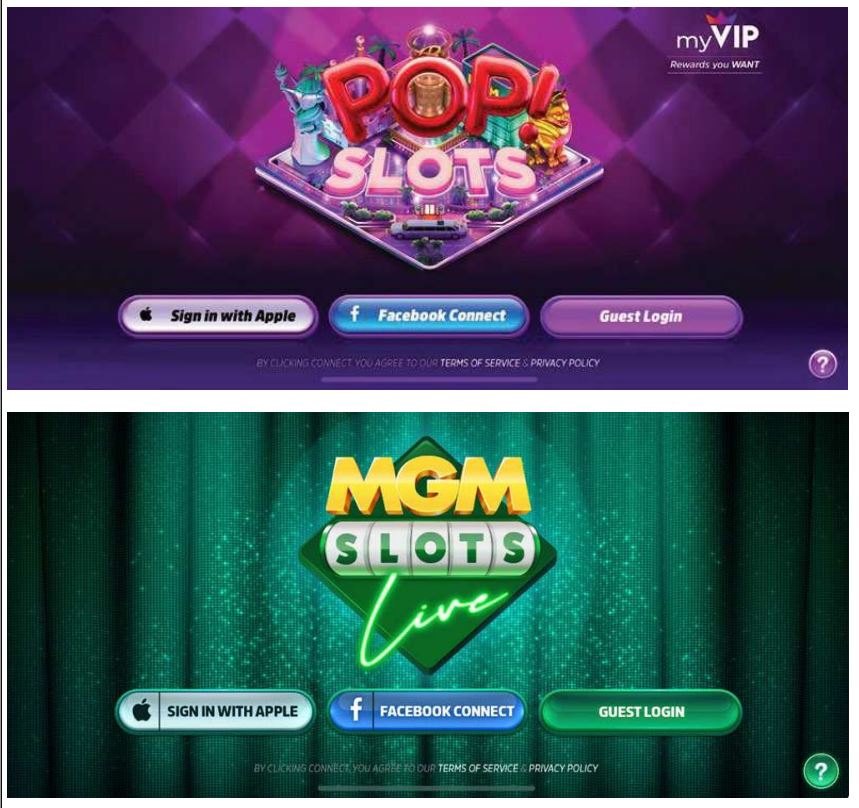

This case involves the following screens:

You may need to enlarge the images to see the purported call-to-action. In the top image, it’s purple lettering on a purple background. Serisouly, who does that? The green one is only slightly easier to see.

The court (correctly) calls this implementation a “sign-in-wrap” (ugh), but still goes through the standard analysis to identify consumers’ manifestation of assent. The court hunts for evidence that consumers had actual knowledge of the terms, but comes up dry. The court says the defendants’ arguments “seem to distill the issue to one of mere proximity of a notice to a sign up or other action button. But it is not that simple to establish notice.”

Without showing consumers had actual notice of the terms, the TOS can still form if consumers had inquiry notice of it. That didn’t happen here:

the font size of the notice is significantly smaller than the font used in the surrounding website elements, and the color of the notice is so similar to the background color of the game homepage that it is barely visible to the naked eye. Further, as in Berman, the middle of the screen includes brightly colored graphics (that in this case also include movement and flashing lights), which distract the user from the comparatively small notice.

Additionally, the hyperlink is not underlined, and the font color of the hyperlink is not so contrasting as to clearly suggest that it is a hyperlink: while it is in a lighter font than the rest of the notice, it is relatively inconspicuous compared to the bright, flashing lights of the logo above it. And while the hyperlink is capitalized, which the court notes in Berman is a customary design element indicative of a hyperlink, so is the rest of the text in the notice, concealing the hyperlink from the user.

I know this is a lawyer’s perspective, but I think the only bright flashing items on a TOS formation page should be the TOS call-to-action… 🤣

The court acknowledges that the call-to-action is right below the action buttons. However, “proximity alone is not enough to give rise to constructive notice. Considering the webpages as a whole, the Court cannot find that Defendant’s website sufficiently provided reasonably conspicuous notice to Plaintiff and other users.”

The court also has a problem with the call-to-action verb mismatch with the action button text:

the notice states: “BY CLICKING CONNECT YOU AGREE TO OUR TERMS OF SERVICE & PRIVACY POLICY.” First, this language is listed in font that is significantly smaller than the words on the buttons above it and are in a color so light and transparent that the existence of the words is barely visible and could be easily missed. Second, there is no “connect” button for a user to utilize—the three buttons that a user might use to connect to Defendant’s game are (1) “Sign In with Apple”; (2) “Facebook Connect”; and (3) “Guest Login.” Arguably, a user connecting with the “Facebook Connect” button might be manifesting assent, but a user connecting with either the “Sign In with Apple” or “Guest Login” buttons is in no way “clicking connect,” as the notice states.

To be clear, properly implemented sign-in-wraps generally fare pretty well in court, so this ruling isn’t a cautionary tale about sign-in-wrap enforceability generally. Instead, it’s a reminder that the TOS formation needs to be properly implemented, and this implementation was a far cry from best practices. Fortunately, the problems with these screens are quite easy to correct, which makes it baffling why they weren’t actually corrected.

Case Citation: Kuhk v. Playstudios Inc., 2024 WL 4529263 (W.D. Wash. Oct. 18, 2024)

Pingback: Links for Week of November 1, 2024 – Cyberlaw Central()

Pingback: Another "Sign-in-Wrap" TOS Formation Process Fails-Morrison v. Yippee - Technology & Marketing Law Blog()