Amazon Isn’t Liable for Selling Suicide “Kits”—McCarthy v. Amazon

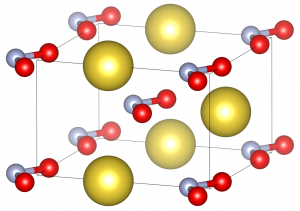

This case involves the tragic suicide of two teenagers, both of whom died by consuming sodium nitrite they purchased from a third-party Amazon merchant (Loudwolf). Sodium nitrite has several socially beneficial commercial uses, including being used (in small quantities) as a food preservative and an antidote to cyanide poisoning. However, in undiluted form, it’s toxic.

The plaintiffs allege that sodium nitrite has “become a highly recommended suicide method on the pro-suicide website Sanctioned Suicide,” and that site also provides recommended consumption practices for maximum likelihood of death. Allegedly, Amazon was repeatedly notified of buyers’ misuse of sodium nitrite but didn’t redress the issue, and it allegedly screened out third-party reviews warning against the product’s use for suicide.

The plaintiffs sued for negligence and related claims. The court dismisses the lawsuit against Amazon.

Product Liability—Negligent Conduct

The plaintiffs’ core claim is that Amazon sold sodium nitrite without adequate warnings. The court rejects this assertion primarily because additional warnings would not have changed the decedents’ behavior:

the Sodium Nitrite was not defective, and that Amazon thus did not owe a duty to warn…the Sodium Nitrite’s warnings were sufficient because the label identified the product’s general dangers and uses, and the dangers of ingesting Sodium Nitrite were both known and obvious. The allegations in the amended complaint establish that Kristine and Ethan deliberately sought out Sodium Nitrite for its fatal properties, intentionally mixed large doses of it with water, and swallowed it to commit suicide….the risk associated with intentionally ingesting a large dose of an industrial grade chemical is also obvious…In this case, the danger was particularly obvious because the Sodium Nitrite “was not marketed as safe for human consumption or ingestion,” and appears to have been categorized as “Business, Industrial, and Scientific Supplies”…

given Kristine and Ethan’s knowledge regarding the dangers of ingesting Sodium Nitrite as well as the general warnings provided on the bottle and the obvious dangers associated with ingesting industrial-grade chemicals, the court concludes that the Sodium Nitrite’s warnings were not defective. Amazon therefore had no duty to provide additional warnings regarding the dangers of ingesting Sodium Nitrite…

even if Amazon owed a duty to provide additional warnings as to the dangers of ingesting sodium nitrite, its failure to do so was not the proximate cause of Kristine and Ethan’s deaths…Kristine and Ethan sought the Sodium Nitrite out for the purpose of committing suicide and intentionally subjected themselves to the Sodium Nitrite’s obvious and known dangerous and those described in the warnings on the label. Plaintiffs do not plausibly allege that better warnings from Amazon would have discouraged Ethan and Kristine from ingesting sodium nitrite.

In a footnote, the court adds that the decedents’ age doesn’t affect the analysis:

The fact that Amazon allegedly continued to sell the Sodium Nitrite to “children” after it “knew [the Sodium Nitrite] was used for suicide” does not change this conclusion. “[L]iability is not imposed simply because a product causes harm,” even with “products used by children.”

Product Liability—Intentional Concealment

Amazon only invoked 230 for its alleged removal of reviews warning against suicide, not the other claims. This claim is preempted by Section 230:

Amazon only invoked 230 for its alleged removal of reviews warning against suicide, not the other claims. This claim is preempted by Section 230:

- ICS provider. Undisputed.

- Publisher/speaker claims. Removal of reviews is a publication function. Cites to Rangel v. Dorsey and Riggs v. MySpace.

- Third-Party Content. The reviews were provided by third parties.

Negligence/NIED

The court says the common law negligence claims are preempted by the applicable products liability statute. “Plaintiffs seek to hold Amazon liable for its role in facilitating the sale of Sodium Nitrite to Kristine and Ethan through Amazon.com,” and this constitutes “marketing” which puts it squarely in the statutory scope.

Implications

Washington-specific ruling. Some of this ruling turns on the specific ways that Washington structures its statutory and common law negligence claims. Though the substantive outcome should be the same in other jurisdictions, other courts could in theory distinguish this ruling on those grounds.

Plaintiffs’ claims are problematic. It’s difficult to discuss this case clinically because of the tragedy around the suicides. My heart goes out to the decedents’ family and friends. However, purely from a legal standpoint, this case was deeply problematic. Sodium nitrite has both legitimate and illegitimate uses, and we don’t want legal liability to curb the legitimate activity.

Furthermore, Amazon and Loudwolf didn’t market sodium nitrite as a suicide method (and the results might have been the same even if they had). Instead, they sold an article of commerce to buyers who had intentions that weren’t known to or knowable by Amazon. In this respect, virtually every physical item on Amazon has the capacity to cause physical injury if the buyer wants to misuse it, and more legends and warnings wouldn’t change that. The court didn’t cite the Taamneh ruling for the common law principles, but its conclusion is consistent with the Supreme Court’s discussion that being open for business doesn’t automatically create liability for misuses.

Once again, Section 230 isn’t the problem. Plaintiffs are embracing Lemmon v. Snap ruling as a way to work around Section 230 for their product liability claims. However, as this case reiterates, the Lemmon workaround doesn’t help plaintiffs as much as they want. Where, as here, the products liability claim is fundamentally based on third-party content, the plaintiffs will always have difficulty satisfying the prima facie elements. In other words, even if Section 230 weren’t on the books, this case would likely fail anyway.

Case Citation: McCarthy v. Amazon.com, Inc., 2:23-cv-00263-JLR (W.D. Wash. June 27, 2023)

UPDATE: The court reiterated its ruling in 2023 WL 5509258 (W.D. Wash. Aug. 25, 2023).