Emoji Version Variations Help Identify Fabricated Evidence–Rossbach v. Montefiore Medical

Rossbach worked at Montefiore Medical Center. She claims her supervisor sexually harassed her and then the center retaliated against her. This screenshot is the evidentiary centerpiece of her claim:

The last line is the court’s: “This image is a fabrication.” A line no litigant ever wants to see in a court opinion discussing their evidence.

Rossbach claimed that she received these text messages on her iPhone 5. She turned over the phone in discovery with a passcode, but the passcode never worked, so the defense could never access the phone’s contents. She claimed she couldn’t provide a screenshot from the phone because the screen was cracked and the screen had ink bleed. None of that makes sense unless it was so bad that the screen was unnavigable, but that wasn’t her argument. She claimed she produced the above screenshot by taking a photo of the iPhone 5 screen with her new phone. That also makes no sense, because plainly you can see there’s no cracked screen or ink bleed.

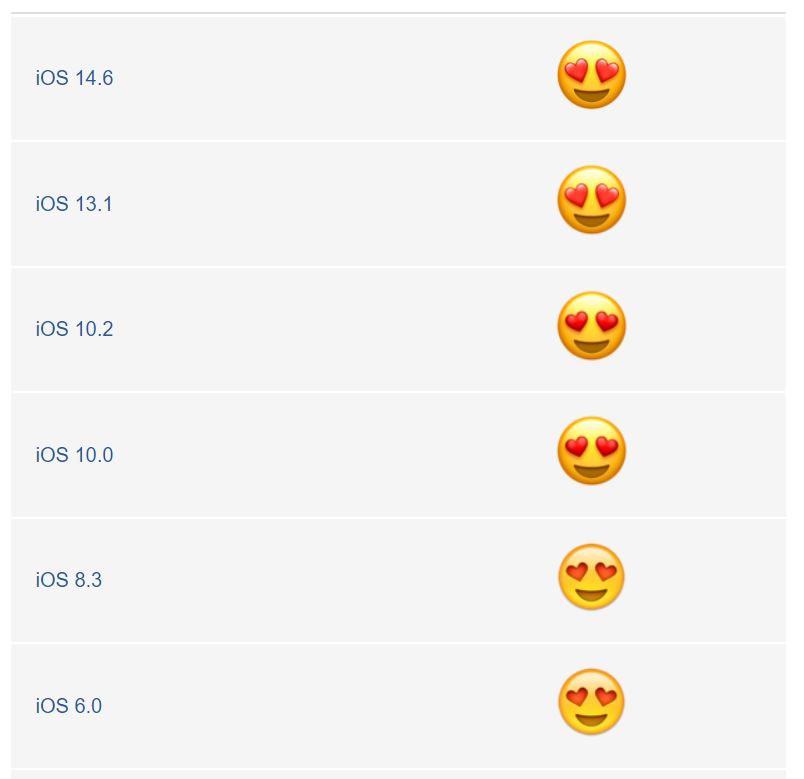

All of this is dubious, but there’s more direct evidence that the screenshot wasn’t from an iPhone 5. See the heart eyes emoji? The court says that particular version of the heart eyes emoji is on iOS13 or later, but the iPhone 5 can’t run anything higher than iOS10. The obvious inference: someone manufactured the screenshot using a more recent phone without realizing that Apple updated the emoji depictions in the intervening OS versions. I’d call that a rookie mistake but honestly, I think many lawyers would have missed the emoji version discrepancy.

[Note: Emojipedia has tracked the history of Apple’s heart eyes depiction. The changes over time are subtle, but you can see that from iOS10 to iOS13, the eyes get bigger:

There also were a few subtle changes from iOS8.3 to iOS10.0.]

This ruling provides some helpful lessons for e-discovery (beyond the obvious advice not to fabricate evidence):

Lesson #1: Emoji depictions in litigation should always come in pairs–what the sender actually saw, and what the recipient actually saw. Never assume they are the same!

Lesson #2: You need to see the emojis as the sender and recipient saw them in, not as they appear on current devices. Thus, in document production, watch out for processing the evidence using current technology because often discovery takes place years after the evidence was initially generated and things could have changed in the interim.

Lesson #3: If you can’t replicate the evidence in its native format, you can do what this defense team did: get declarations from your litigation opponent about the purported hardware/OS versions where the evidence was generated and then use variations in emoji versions like carbon dating to double-check the timeline.

Bonus: keep your cool if your litigation opponent produces smoking-gun evidence until you’ve verified its credibility. As you can imagine, the judge had some pretty harsh words for the plaintiff’s lawyer. Sanctions are forthcoming.

Case citation: Rossbach v. Montefiore Med. Ctr., 2021 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 147031 (SDNY Aug. 5, 2021)