Court Rejects Parler’s Demand That Amazon Host Its Services

Parler, a self-described “conservative microblogging alternative and [competitor] to Twitter,” sued Amazon Web Services for suspending its service. Parler claimed (1) antitrust violations, (2) breach of contract, and (3) tortious interference. Parler sought a temporary restraining order (which the court converted into a preliminary injunction request). The court denied Parler’s request.

Parler, a self-described “conservative microblogging alternative and [competitor] to Twitter,” sued Amazon Web Services for suspending its service. Parler claimed (1) antitrust violations, (2) breach of contract, and (3) tortious interference. Parler sought a temporary restraining order (which the court converted into a preliminary injunction request). The court denied Parler’s request.

Parler allegedly had 15 million accounts, with a million downloads of its app per day. Parler takes a laid back (“reactive”) approach to moderation. Amazon told Parler several times that its users’ content violated AWS’s “acceptable use policy” (AUP). Parler did not deny that its users posted content that violated AWS’s policies, but Parler said it was working to resolve the issue.

Then came the Capitol insurrection on January 6, 2021. On January 8, 2021, Twitter banned President Trump. Apparently there was speculation that “the [former] President would move to Parler” and, as a result, “there was a mass exodus of users from Twitter to Parler.” This led to a backlog of approximately 26,000 posts that Parler acknowledged “potentially encouraged violence.” Amazon told Parler on January 9, 2021 that it would suspend Parler’s services, which it did. Amazon’s action caused Parler’s services to go offline. The next day, Parler filed for a TRO.

Antitrust. Parler claimed that AWS terminated it to benefit Twitter. The court says Parler’s claims were too speculative. Parler and Twitter are not similarly situated because Amazon does not yet provide hosting services to Twitter.

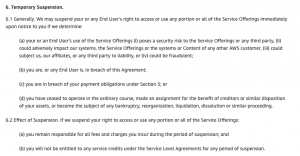

Contract Breach. Parler argued that AWS breached its hosting services contract, because the AWS terms required 30 days’ notice before termination. However, the AWS terms also authorized AWS to terminate the agreement “immediately” where AWS has the right to suspend the services; and Amazon had the right to suspend Parler immediately because of Parler’s contract breach.

Tortious Interference. Parler’s tortious interference claim was not sufficiently pled.

Irreparable Harm. The bar for irreparable harm is high, and Parler did not meet it. Parler also conceded that much of its harm could be compensated by money damages.

Balance of Hardships and the Public Interest. AWS persuasively argued that hosting Parler’s content could lead to violence. Similarly, the public interest does not favor Parler:

The Court explicitly rejects any suggestion that the balance of equities or the public interest favors obligating AWS to host the kind of abusive, violent content at issue in this case, particularly in light of the recent riots at the U.S. Capitol. That event was a tragic reminder that inflammatory rhetoric can—more swiftly and easily than many of us would have hoped—turn a lawful protest into a violent insurrection. The Court rejects any suggestion that the public interest favors requiring AWS to host the incendiary speech that the record shows some of Parler’s users have engaged in. At this stage, on the showing made thus far, neither the public interest nor the balance of equities favors granting an injunction in this case.

The court says it is not dismissing Parler’s claim “at this time”. However, in the Court’s view, Parler has not come close to satisfying the necessary showing to be entitled to a TRO.

__

Parler’s lawsuit seems like a long-shot.

Amazon faces many antitrust concerns, but favoring Twitter does not seem like a credible one. Twitter will not be a big enough part of AWS’s business to influence AWS’s conduct.

Asserting a contract claim against a hosting service is a hail mary case at best. Every hosting service agreement reserves the right to suspend or terminate service for violation of an acceptable use policy—usually a laundry list of content rules that provide multiple justifications to terminate the hosting agreement. The hosting company typically can determine whether content violates its acceptable use policy.

Notwithstanding the relatively easy legal conclusion with respect to Parler’s claims, there are some interesting aspects of the lawsuit:

- Amazon asserted a Section 230 defense. The court does not mention it at all in the ruling.

- Since this involves a private company’s decision to not provide a platform, Amazon isn’t governed by the First Amendment. If anything, a court compelling Amazon to host content could create a First Amendment issue.

- Resolution of the contractual question felt unfair. If there’s a 30 day notice provision, it seems like both parties would have to stick to it absent extenuating circumstances. The fact that AWS could point to a breach to support immediate termination despite a notice provision didn’t make a ton of sense (from a contractual standpoint). On the other hand, AWS actually “suspended” Parler and there’s no dispute it could immediately take this step. Agreements of this nature are notoriously one-sided, and this one is no exception. Since Parler is a business, the court is understandably not sympathetic to its arguments about the hosting agreement being unfairly slanted. The fact that Parler sought a TRO made its arguments even tougher. A breach of contract that warrants a TRO is a rare animal.

- Parler has found another home apparently. Its claim that AWS’s suspension would result in its “extinction” turned out to be hot air. On the other hand, being de-platformed from the major companies would make it a lot tougher to get content or product out there. Parler wasn’t the best poster child for this argument, but it’s certainly an issue.

- Finally, along the same lines, AWS’s conduct is not likely to hold up to scrutiny in terms of whether it’s treating Parler the same as other companies. As any lawyer who touches internet law issues knows, it can be extremely difficult to get content removed from a platform, despite clear and obvious violations of the platform’s acceptable use policy. Platforms exercise their discretion in deciding which content to remove. Inconsistent treatment is not something that should result in a legal claim, but let’s not kid ourselves that AWS’s decision wasn’t spurred by current events and PR considerations.

- It’s interesting to contrast AWS’s actions here with Google’s in the Garcia case (where Google successfully resisted a court order requiring it to take down inflammatory content despite pleas to do so). Platforms will wave the “this content is inflammatory and should be taken down” flag freely, but this is their decision alone. They will resist mightily any external decision that forces them to remove content for similar reasons.

* * *

Eric’s comments: Like so many other #MAGA lawsuits, Parler’s lawsuit was poorly litigated and obviously doomed to fail. Its Sherman Act claim failed because “Parler has submitted no evidence that AWS and Twitter acted together intentionally—or even at all—in restraint of trade.” As Venkat points out, the breach of contract claim was always mockable because AWS’s contract has multiple escape hatches. The tortious interference claim was pure garbage (and it’s always a hard claim to win). As the court says curtly, “Parler has fallen far short” of making the case for preliminary relief. Parler won’t do any better on further proceedings in this case.

I know many people, including Venkat, are concerned about a powerful web host (like AWS) kicking a customer off its network for apparently political reasons. I understand those concerns, but ultimately I don’t share them.

First, AWS must navigate a complex environment where it faces legal, business, and reputational risks for continuing to serve Parler after “knowing” that Parler’s users were using the service to incite violence. Those users may have been conspiring to commit federal crimes, and Section 230 won’t protect Amazon in the event of a federal criminal prosecution. Furthermore, Amazon faced the risks that politicians and the public would attack it for its inaction knowing of the potential harm.

Second, Parler essentially treated AWS as a sole-source vendor of a mission-critical service. Sole-sourcing is always risky for exactly the reasons exposed here–if a critical vendor goes rogue, the business is SOL. Still, sole-sourcing its hosting services was a business choice Parler made. Viewed that way, this case is less about free speech/free expression and more a reminder of why you should never sole-source critical services.

While AWS’s acceptable use policy may seem overreaching, it’s standard for Internet access providers and web hosts. In fact, AWS’s IAPs probably have similar AUP terms with AWS, and it’s possible AWS had to flow down the requirements of its upstream IAPs. Indeed, AWS’s request of Parler was actually quite reasonable–you can stay if you clean up the garbage, which Parler couldn’t do because it had no organized content moderation function. That’s another bad business decision by Parler.

Indeed, Parler’s “laissez faire” content moderation approach has always been (1) stupid, (2) untenable, and (3) a lie. If a service doesn’t adequately moderate its content, it will be overrun by so much garbage that it inevitably will fail in the marketplace. Parler is the latest case study of how you can’t build a sustainable business around a cyber-cesspool. It’s also a cautionary tale for regulators tempted to cite Parler’s emergence as a reason to target Section 230; the fall of Parler came quickly, emphatically, and most importantly, inevitably. This pattern will repeat with any Parler successors who also build cyber-cesspools, for the same reasons, and that will happen without any Section 230 reform. The market mechanisms work better here than perhaps regulators appreciate.

Finally, this situation reminded me of an incident from almost 20 years ago. AT&T had a “pink contract” with a spammer to overlook their spamming despite AT&T’s AUP (because AT&T wanted the spammer’s money, natch). However, AT&T took the spammer offline when the pink contract was publicized. Though AT&T screwed the spammer, it’s hard to feel too much sympathy for the spammer, no? As the incident highlights, the selective application of draconian AUPs is as old as the Internet, and that’s another reason businesses should never sole-source to any vendor who imposes vendor-favorable AUPs.

Case citation: Parler, LLC v. Amazon Web Services, Inc., 2021 WL 210721 (W.D. Wash. Jan. 21, 2021). Parler’s complaint. Amazon’s response.

Pingback: News of the Week; January 27, 2021 – Communications Law at Allard Hall()