Another Terrible Copyright Ruling on IAPs’ Liability for Users’ File-Sharing–Warner v. Charter

This is a copyright infringement lawsuit against Charter, an Internet access provider, for users’ copyright infringements by file-sharing. I comprehensively blogged the magistrate report in this case back in October. In that blog post, I described the magistrate’s report as “a major win for copyright owners in their irrepressible quest to deputize IAPs as their copyright sheriffs.” Charter objected to the magistrate report’s analysis of vicarious copyright infringement. The district court judge’s response opinion is…UGH.

This is a copyright infringement lawsuit against Charter, an Internet access provider, for users’ copyright infringements by file-sharing. I comprehensively blogged the magistrate report in this case back in October. In that blog post, I described the magistrate’s report as “a major win for copyright owners in their irrepressible quest to deputize IAPs as their copyright sheriffs.” Charter objected to the magistrate report’s analysis of vicarious copyright infringement. The district court judge’s response opinion is…UGH.

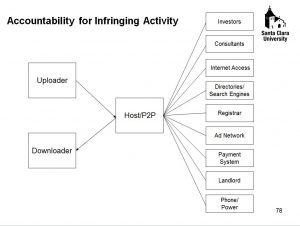

As a reminder, vicarious copyright infringement has three elements:

- direct copyright infringement by someone else. In this case, the presumed direct infringers are the IAP subscribers who use BitTorrent;

- the defendant’s right and ability to supervise the direct infringement (sometimes the verb “supervise” is replaced by “control”); and

- the defendant’s direct financial interest in the direct infringements (sometimes stated as “direct financial benefit”–same thing).

Direct Financial Interest

A quarter-century ago, in the Fonovisa case, the Ninth Circuit added a second way of measuring “direct financial interest” to include when infringing works act as a marketing “draw” to pull in customers. Unfortunately, this reframing decouples the prong from financial interests. This leads to wacky outcomes like the Napster case from the 2000s, where the Ninth Circuit found that Napster’s database of infringing works drew in customers, even though Napster had never made a dime in revenues, let alone profits. In other words, Napster had a direct financial interest in its users’ infringing activity even though it had NO financial interest in the activity at all. That kind of word-twisting is a contributing factor to why most people hate lawyers.

With that backdrop, it’s understandable why Charter contested the “direct financial interest” prong. It charges a monthly subscription fee that doesn’t vary with the amount of infringing activity. The subscriber who never infringes pays the exact same amount as the subscriber who always infringes.

Nevertheless, the magistrate said that Charter’s customers were drawn to Internet access subscriptions by their ability to use BitTorrent. That might be true in an abstract, theoretical sense, but I doubt any Charter subscriber procures Internet access solely because they plan to infringe. Instead, they subscribe because Internet access is essential to modern living, especially in a COVID-19 shutdown world where many of our key institutions (employers, schools, governments) now function virtually.

Thus, Charter sensibly argued that the opportunity to infringe was not THE draw that pulled in subscribers. The district court judge’s response is that the infringement potential doesn’t need to be THE draw to satisfying the “direct financial interest” prong; it only needs to be A draw, possibly one of many. For example, the court says:

Infringing activity may be merely an added benefit to subscribers and not a draw in itself. It may also be one among several draws to Charter’s services. It may also be the draw for subscribers to subscribe to Charter. The latter two cases would be sufficient to show that Charter incurred a direct financial benefit from the infringing activity.

This response may be supported by the precedent, but it’s tone-deaf. If the opportunity to infringe represents 0.1% of the motivation for 0.1% of Charter’s subscribers to subscribe, the court implies that’s enough to potentially hold Charter vicariously liable for 100% of the copyright infringements by 100% of its subscribers. FFS.

The district court judge says the plaintiffs sufficiently alleged facts showing that infringing activity was a draw to Charter’s subscribers:

Plaintiffs allege not only that Charter subscribers have used Charter services to infringe their content, but that subscribers are motivated to subscribe by Charter’s advertisement of features attractive to those who seek to infringe, such as fast download speeds for “just about anything.” Plaintiffs allege hundreds of thousands of specific instances in which that Charter subscribers have illegally distributed and copied their works. Plaintiffs also allege that infringing activity accounts for 11% of all internet traffic, indicating that though some subscribers may be drawn by the ability to download authorized content, a significant number of subscribers are likely drawn by the ability to download infringing content….

the volume and popularity of plaintiffs’ copyrighted works, the commonality of infringing downloading, and the frequency that plaintiffs’ works in particular are downloaded allow for the reasonable inference that at least some of Charter’s subscribers were drawn by the ability to infringe on plaintiffs’ works.

In other words, these facts just allege that Charter operates a standard IAP.

Supervisory Right

Every IAP has the technical and legal power to terminate subscribers. Is that enough to satisfy this prong? The court says sure: “Charter can ‘stop or limit’ infringement of plaintiffs works by terminating those users about whom it is notified.” Of course, there will be massive adverse consequences to non-infringing activity from such terminations, but the court’s attitude is ¯\_(ツ)_/¯. The court sees the ability to turn off Internet access for infringing subscribers as a feature, not a bug: “Charter can certainly limit its subscribers’ ability to infringe by blocking their access to the internet through Charter. I find that this is sufficient to allege that Charter has the ability to control infringement.”

Conclusion

In my prior post, I wrote: “copyright owners aren’t going to stop until they turn IAPs into their copyright cops. This has their dream for decades, and this ruling moves one step closer to it.”

In particular, the opinion highlights how we desperately need a well-functioning 512(a) safe harbor for Internet access providers. Over and over again, the court cites facts that just show Charter offered Internet access, which the court treats as enough to establish a prima facie case of vicarious copyright infringement. That can’t be right.

The damage in this case can be traced to prior rulings requiring that IAPs “terminate repeat infringers” based on notices of claimed infringement rather than judicial findings of actual user infringement. By creating that bypass, copyright owners can work around 512(a), which opens up a Pandora’s box of liability that does not bode well for the future of Internet access.

The Senate is currently undertaking a 20 year review of the DMCA. It would be wise for Congress to figure out why 512(a) failed to achieve its purported purpose–and how it might be rehabilitated.

Finally, this ruling shows how far the vicarious copyright infringement doctrine has strayed from its roots. Vicarious copyright infringement started as a branchoff of agency law. The IAP-subscriber relationship bears absolutely no resemblance to a principal-agent relationship, yet here we are. We need better limiting principles to the vicarious copyright infringement doctrine so that it does not extend, illogically, to typical vendor-customer relationships.

Case citation: Warner Records Inc. v. Charter Communications, Inc., No. 19-cv-00874-RBJ-MEH (D. Colo. April 15, 2020)