Emoji Law 2018 Year-in-Review

As I’ve mentioned before, I track every U.S. court opinion in Westlaw and Lexis that references “emoji” or “emoticon.” This is not a comprehensive census for several reasons, including my inability to set up alerts when a court displays the symbol without calling it an emoji or emoticon (which, in many emoji cases, aren’t even displayed in Westlaw or Lexis) and the other known skews and limits of Westlaw’s and Lexis’ case collections. Still, FWIW, I’ve posted the updated roster of cases.

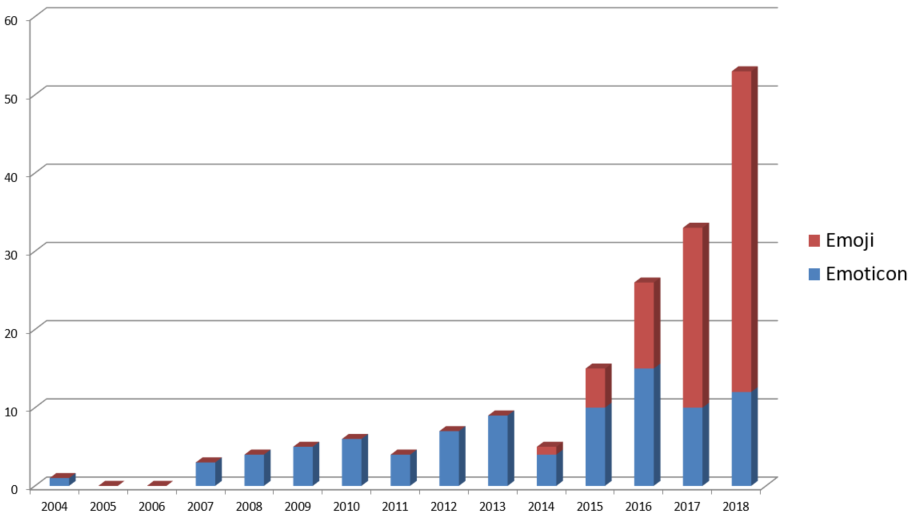

As expected, the number of emoji/emoticon case references are growing in a typical exponential J curve. By my count, there were 53 such cases in 2018, compared to 33 in 2017. I count a total of 171 cases all-time, of which over 30% were in 2018.

As the above chart shows, the relative frequency of the term “emoji” has completely eclipsed the term “emoticon.” The chart is skewed a bit by the fact some opinions use both terms, and I counted those opinions only as referencing emojis. Still, while emoticons are likely to remain part of the lexicon for the foreseeable future, clearly emojis are the future.

While the number of opinions referencing emojis is growing rapidly, 2018 did not see any major substantive rulings interpreting emojis. In 37 of the 53 cases, the term emoji or emoticon only appeared a single time, usually meaning that the emoji/emoticon was just an incidental part of the evidence. None of the other 16 cases broke any interesting new ground on emoji interpretations.

Nevertheless, I remain convinced those they are coming! In support of that, I call your attention to a terrific paper by Hillberg et al, “What I See is What You Don’t Get: The Effects of (Not) Seeing Emoji Rendering Differences across Platforms.” From the summary:

at least 25% of respondents were unaware that the emoji they posted could appear differently to their followers. Additionally, after being shown how one of their tweets rendered across platforms, 20% of respondents reported that they would have edited or not sent the tweet. These statistics reflect millions of potentially regretful tweets shared per day because people cannot see emoji rendering differences across platforms

When the authors say “millions of potentially regretful tweets shared per day,” the law professor translates that into “lawsuits aplenty.”

For more on the fascinating world of emoji law, see my roundup post, Everything You Wanted to Know About Emojis and the Law.

Finally, if you’re in the Bay Area on February 12 at noon, I’m speaking at Santa Clara Law about Emoji Law at the kickoff event for the law school’s brand new Internet Law Student Organization (check out our group photo). It’s open to the public, so we’d love to have you join us. Yes, I will be wearing my emoji tie at the talk!

Pingback: What's New With Emoji Law? An Interview - Technology & Marketing Law Blog()