The Sixth Circuit Wades Into Online TOS Formation (and Leaves Me More Confused Than Ever)–Dahdah v. LowerMyBills

TL;DR: The court provides this overview:

LowerMyBills.com refers internet users who are interested in refinancing their home mortgages to affiliated lending partners, including Rocket Mortgage. The website tells users that they will agree to its hyperlinked “Terms of Use”—including a mandatory arbitration provision—if they click on a particular button. Michael Dahdah visited this website three times, inputted his information, and clicked the critical buttons. LowerMyBills referred him to Rocket. When Dahdah later received calls from Rocket that he did not want, he sued the company in federal court. Rocket responded by invoking LowerMyBills’ arbitration provision. But the district court held that Dahdah’s “click” did not create an enforceable agreement. We disagree. Under the significant body of circuit precedent interpreting California law, LowerMyBills gave Dahdah sufficiently conspicuous notice that he would accept the proposed terms by clicking the button. So his decision to take this action qualified as a valid “acceptance” of LowerMyBills’ “offer” to contract. The district court thus should have granted Rocket’s motion to compel arbitration.

* * *

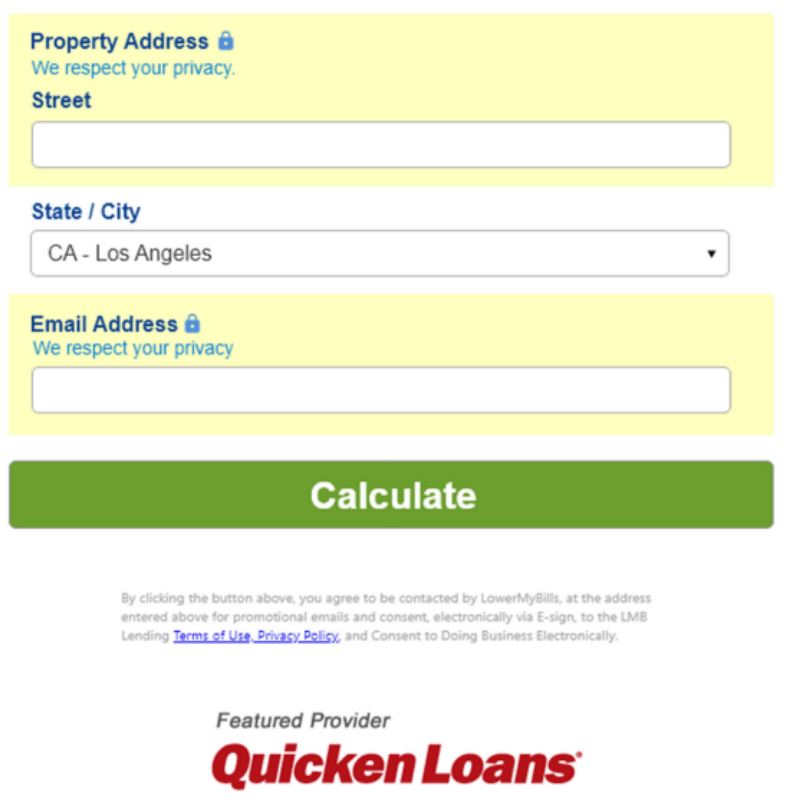

Let’s dig into the details, starting with the relevant screens. The plaintiff went to LowerMyBills’ site and requested information about mortgages. The court focuses on the following two screens (the fourth and fifth pages in a 5-page sequence). A screenshot of the bottom of the fourth screen:

A screenshot of the bottom of the fifth screen:

[By redacting the screenshots to only show the page bottoms, the court removed the TOS formation process from the full context. This supports the court’s pro-formation bias by making the pages look simpler than they actually were.]

As you can see, these screenshots look like pretty standard “sign-in-wraps.” The court characterizes them as “a hybrid offer (not a clickwrap or browsewrap offer).” The court prefers the hybrid language because the same methodology applies to sign-in-wraps and other formation processes that aren’t clickwrap/scrollwraps or browsewraps. The court rejects the plaintiff’s argument that this was a browsewrap:

Browsewrap offers seek to create contracts when users simply browse a webpage (hence, their name). LowerMyBills did not propose that type of offer. It required users to take a specific step to accept its offer: click the relevant buttons.

The Sixth Circuit applies California law to these screenshots (both parties agreed on that choice), which is a little dicey because the Sixth Circuit isn’t a repeat player with California TOS formation law. As an example, the Sixth Circuit completely ignores the Godun decision even though I think Chabolla and Godun can’t be understood without reference to the other.

[Personnel notes:

- The opinion was written by a TAFS judge (TAFS = Trump-Appointed Federalist Society). TAFS judges’ opinions routinely are distinctive compared to non-TAFS opinions (not necessarily in a good way). I thought this opinion was disorganized (my blog post merges related topics that were confusingly addressed in disjointed locations throughout the opinion) and overrelied on cherrypicked precedent (a hallmark of TAFS opinions).

- For a court applying California law outside of California, it was conspicuous that none of the lawyers listed on the opinion caption are based in California…]

The Court’s Description of TOS Formation Law

The Wrap Taxonomy

- “any reasonable person would conclude that so-called scrollwrap or clickwrap offers objectively convey the website operator’s “manifestation of [a] willingness to enter into a bargain” with website users”

- “So-called browsewrap proposals fall on “the other end” of potential offers….courts often hold that these offers cannot create valid agreements because they leave users “unaware” that the operator has even proposed an offer”

- “many proposals fall in between these extremes. These “hybrid” offers (what some courts have called “sign-in wrap” offers) present the trickiest cases.”

Sign-In Wrap (“Hybrid”) Requirements

In determining if an offer is reasonably conspicuous, this court asks Four Questions (no, not those questions):

Q1: “Did the website display the offer on an “uncluttered” page, or on a page filled with items that will “draw the user’s attention away from” the proposal?” “Simple streamlined designs” are more likely enforceable than “a page with lots of distractions.”

Q2: “Did the website operator place the proposed offer close to—or away from—the button that a user must click to signal the user’s acceptance of the proposal?” The closer the offer is to the action button, the more conspicuous it is.

Q3: “Did the website operator use a font size or color that would draw attention to the proposal?” The court says that it’s more likely conspicuous when sites use “a larger font or at least colored hyperlinks.” This is not a faithful characterization of Chabolla/Godun, which had exacting requirements for both fonts AND hyperlink presentations. It’s telling that the court favorably cites Selden v. Airbnb, a DC Circuit case (i.e., not a California case) that predates Chabolla/Godun, to support its summary rather than any Ninth Circuit case.

Q4: “Did the website operator and users engage in the kind of interaction that one would expect to include contractual terms?” Users expect terms with continuing relationships and not for one-off interactions.

These Four Questions are similar–but not identical–to the Ninth Circuit standards. Here’s how I summarize those standards in my Internet Law course:

Who Decides

The court says that if the facts about what happened aren’t in dispute, the court can rule on the formation process as a matter of law rather than send the formation question to the jury.

Application to This Case

Reasonably Conspicuous Notice

The court says the conspicuousness of the notice is a “close question.” Here’s why the court concludes that the notice was reasonably conspicuous:

the proposal on the fourth page followed a “simple design” that did not contain much clutter (other than a logo for Quicken Loans as the “Featured Provider”). Selden, 4 F.4th at 156. [Reminder: Selden is a DC Circuit opinion that predates Chabolla/Godun] In this respect, then, this page resembles the simple sign-up pages for Uber or Airbnb. And it differs from Fluent’s webpages in Berman, which contained other eye-catching images and information. Admittedly, the fifth page had far more terms than the fourth page. It also identified Dahdah’s consent to the specific “Terms of Use” in the second of four paragraphs of details. But we view this page as serving a belt-and-suspenders role for the fourth page’s proposal. And we resolve this case based on the notice that consumers would have received across the pages in combination….

LowerMyBills placed the proposal “directly” “below the action button” on each of the pages. And it used a “dynamic scrolling function” in which these pages automatically scrolled down as users inputted information in the boxes. So users would always see the offer on the same screen as the action buttons.

The plaintiff pointed out that the 5-screen formation process was confusing because the prior screens had a similar “calculate” button without terms. The court says that multi-screen processes are OK, noting that Uber’s process had two screens. But I also note (which the court didn’t) that Chabolla said: “three faulty notices do not equal a proper one.” I think the court would say that the fourth and fifth screens are each independently sufficient, but I wanted to see more thoughtful discussion about how the multiple screens reinforce or conflict with each other.

The court notes that LowerMyBills used a “very small font,” which calls it “a legitimate concern.” As I teach my students, the offer language should never be in the smallest font on the page. In Chabolla, a TOS formation failed in part because the offer language’s font was “notably timid in both size and color” (a critique that could apply here). In response, the court cherrypicks the precedent and says that the font size might be comparable to the font sizes used by Uber or LiveNation (both are pre-Chabolla cases, and Uber is a 2nd Circuit case). Also, the hyperlink was in “bright blue” on a white background, so “LowerMyBills did not hide the critical hyperlink using the same font color as the other text.” (The Ninth Circuit would treat a different font color for the links as mandatory, not a plus factor).

The court also struggles with whether the interactions with LowerMyBills was a one-off or ongoing relationship given that they were largely acting as a referral service (the court says this is also a close call). The court makes this empirical claim without a scintilla of empirical support: “reasonable users also would expect that the free referral service comes with some contractual strings attached….given that the site matches users with potential lenders, we cannot say the objective user would fail to anticipate some sort of continuing relationship.” [Insert goose meme: relationship with WHO?] 🤔

The court says that it’s OK the offer language was below the action button rather than above because “Other courts have enforced these offers when placed below rather than above the button that signaled the user’s assent.”

Manifestation of Assent

The court says concluding “that Dahdah took actions showing his assent to LowerMyBills’ offer becomes “straightforward” once we conclude that the offer was reasonably conspicuous.” The plaintiff clicked on the green “calculate” and “calculate your free results” buttons.

The plaintiff weakly attacked the call-to-action language, which lets the court skirt any serious analysis. But look back at the text: it says “by clicking the button above,” which we could assume refers to the green button right above that text. But there are surely other “buttons” on the screen above the text (remember, the court clipped the screenshot, improperly IMO), which would make the cross-reference ambiguous. If there are more “buttons” “above,” what should have happened?

Also, the Chabolla opinion rejected a TOS formation when the offer language said “by signing up” and the action button said “continue.” Would it matter to Chabolla that the offer language didn’t precisely describe the action button?

Arbitration Terms

The court acknowledges that LowerMyBills’ TOS was silent on many key provisions about the arbitration, such as selecting an arbitration service. However, the provision says that the Federal Arbitration Act applies, and the court says that’s good enough to gap-fill all missing arbitration terms.

Implications

Would this case have turned out differently if it had actually been in a California court? I believe Chabolla and Godun changed a lot about TOS formation, and this court mostly disregarded those cases to rely on pre-Chabolla cases, some of them from courts outside California. So, I believe this ruling is not consistent with California courts. But really, who knows? TOS formation remains another Calvinball area of Internet law.

To be fair, LowerMyBills’ TOS formation process might not be condemnable despite their sloppiness. Obviously it could be easily improved (2 clicks, please), but it’s pretty consistent with the old standards for TOS formation. However, I think it’s disingenuous to treat this opinion as consistent with California law without wrestling more thoughtfully with the effects of Chabolla and Godun.

Case Citation: Dahdah v. Rocket Mortgage, LLC, 2026 WL 194455 (6th Cir. Jan. 26, 2026)