More Chaos in the Law of Online Contract Formation

Another 3k+ word post about the jurisprudential chaos in online contract formation law. You’ll notice that this post gets increasingly surly as the cumulative effect of the judicial inanity weighed on me. Two top-line takeaways you might get from this post:

- A two-click formation process avoids the risk of judges moving the goalposts about formation, and

- If you are amending your TOS, have an airtight plan for building a credible evidentiary record.

In re: StubHub Refund Litigation, No. 22-15879 (9th Cir. August 9, 2023)

This case involves StubHub’s obligations to provide refunds due to COVID cancellations. The district court said that the buyers who made their purchases on the website had to go to arbitration, but the buyers who made their purchases on their mobile devices could stay in court. The Ninth Circuit says that the users who initially registered on the website had to go to arbitration, but the users who registered only via the mobile app could stay in court.

The court explains:

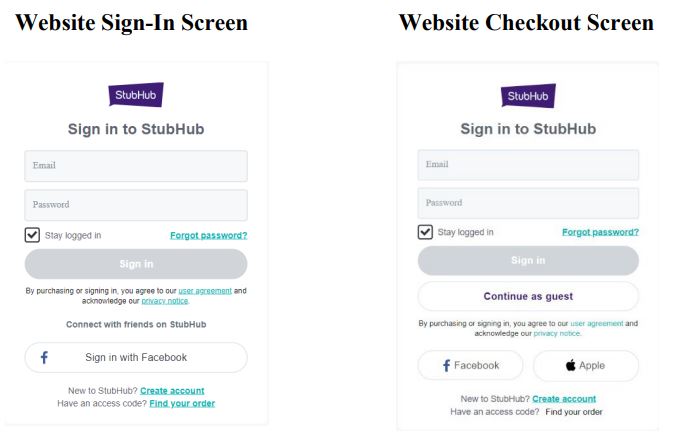

StubHub’s website sign-in screen that these Plaintiffs viewed provided sufficient notice of their agreement to arbitrate any disputes. The sign-in screen contains hyperlinks in offset, bolded, underlined, and bright blue typeface, in close proximity to the sign-in button. In fact, the website sign-in screen is nearly identical to the website checkout screen that the district court found was sufficient to compel the other forty-eight Plaintiffs to arbitration

The court shows the screenshots:

Looks like a standard “sign-in-wrap” formation process. I can see why the 9th Circuit couldn’t distinguish between the legal consequences of these two screens.

The court says it’s immaterial that there is a potentially long time delay between user registration and the purchases. “[O]nce an individual registers for an online service or account and assents to its broad terms, she is bound by those terms if she accesses the website at a later date, unless the terms or conditions have changed.”

While the website formation process succeeds, the following mobile formation screen fails:

What went wrong? Citing Sellers v. Just Answers, the court says that call-to-action conspicuousness is determined by:

(1) the size of the text; (2) the color of the text compared to the background; (3) the location of the text and its proximity to where the user clicks to consent; (4) the obviousness of an associated hyperlink; and (5) other elements on the screen which clutter or obscure the textual notice

To me, the mobile formation screen looks pretty similar to the website sign-in process. Both are suboptimal because the call-to-action is the smallest font on the screen, below the “action” button, and doesn’t require a second click. But acknowledging those limitations, I don’t know that the mobile formation process is materially worse than the website formation process.

The court sees it differently. The mobile formation process fails because:

The color of the relevant text is gray and does not stand out against the white background; it is not obvious to the user that the text is hyperlinked; and the bright pink sign-up button obscures the muted colors of the relevant text providing notice. While the hyperlinked text is bolded, it is not underlined, which generally indicates that the text is hyperlinked. This is distinct from the text of the website checkout and sign-in pages, in which the term “User Agreement” is underlined and in bright blue font to emphasize that it is hyperlinked.

Count this as another opinion where underlining is required to signal a hyperlink. And I guess pink is overly distracting to this judge?

This is probably a frustrating ruling for most parties. For StubHub, it will have to fight the same battle in two venues (court and arbitration) with the risk of inconsistent judgments, plus the court’s holding indicates that the court cases will proceed without any of StubHub’s TOS protections. Those factors counsel towards StubHub settling the court cases and doubling down on the arbitrations.

Sadlock v. Walt Disney Corp., Case No. 22-cv-09155-EMC (N.D. Cal. July 31, 2023)

This is a lawsuit over Blue Kai’s alleged keystroke logging on ESPN.com. Disney tries to send the case to arbitration. This opinion is wild. The court rejects its online formation process–a panic-inducing result–but finds Disney remarkably saved itself by amending the terms in post-transaction emails. Definitely don’t try to replicate Disney’s narrow escape if you can avoid it!

Here’s the screen that failed:

Looks pretty standard to me. The fonts are small, but the call-to-action has the right specificity and is above the action button. Why does the court say “the screen at issue did not provide reasonably conspicuous notice based on the totality of the circumstances”?

- The subscriber agreement isn’t mentioned until the screen bottom.

- The call-to-action is in a small font, which is smaller than other fonts on the page.

- The font is whitish/gray, not white, and doesn’t stand out against the black background.

- the blue font for the link to the subscriber agreement “appears muted” and doesn’t stand out against the black background

- “The hyperlink to the “Subscriber Agreement” is buried in six lines of text and is located five lines away from the “Agree and Subscribe” button.” [Note this is a classic problem with layered notices–the additional disclosures create visual separation]

- The page has other elements that are in larger fonts and are more eye-catching, including the focus on payment for the service.

- The court also questions the “agree & subscribe” button, saying that the subscriber knew he was buying the subscription but not that he was agreeing to the terms. [Notice how a separate checkbox for the agreement completely eliminates this risk].

I don’t know, the court’s points all seem like a stretch to me. Sure, Disney could have and should have improved this UI, but the test is whether a reasonably prudent consumer would have notice of the applicable terms. Given users’ experience navigating TOSes, I think this page easily passes the test.

The court distinguishes Lee v. Ticketmaster, a 9th Circuit memo opinion from 2020 that I did not blog. The court explains:

In Lee, the court found the Terms of Use sufficiently conspicuous even though they were referred to as part of a broader payment screen. But notably, the Terms of Use in Lee were referred to in two different screens – i.e., not just the payment screen but also the sign-in screen. The sign-in screen in Lee was far simpler and less cluttered compared to the screen at issue in this case. Moreover, even the payment screen in Lee, taken in isolation, was simpler and more direct; for example, there was a single sentence immediately above the “Place Order” button: “By clicking “Place Order, you agree to our Terms of Use.” In contrast, here, the reference to the Subscriber Agreement was part of a three-sentence, six-line paragraph, and the term “Subscriber Agreement” was five lines above the “AGREE & SUBMIT” button. Finally, Lee is different from the instant case in that each time the plaintiff signed in or made a payment, he was given notice about the Terms of Use. Here, there was just a one-time payment to sign up for the Disney+ streaming service

Again, it sounds to me like the court is reaching. But ultimately, the onus is on Disney to create a contract formation process so conspicuous that a court can’t reach decisions like this. If you cut it close on TOS formation, you can’t really complain if the court moves the goalposts on you.

After this surprise result, the court unleashes a second surprise and says Disney formed the arbitration provision in post-agreement emails. O RLY? Here’s how the court reaches that result:

each email had the subject line “We’re updating our Subscriber Agreement,” and the body of the email began with, in effect, a large header repeating that message: “WE’RE UPDATING OUR SUBSCRIBER AGREEMENT.” The first full paragraph reiterated that updates to the Subscriber Agreement were being made, and the second paragraph explained that, “[f]or prior and existing subscribers, like you, these terms will be effective beginning on November 3, 2022.” The next paragraph “encourage[d]” Mr. Sadlock to “review the updated Subscriber Agreement in full and save a copy for your files. Once effective, it will govern your use and enjoyment of your Disney+ or ESPN+ subscription.” Although the term “Subscriber Agreement” was only underlined and not enhanced by a different color font, it was clear that this was a hyperlink given the context of the sentence, encouraging Mr. Sadlock to review the agreement. That the underlined term was in fact a hyperlink was underscored by the fact that the only other terms that were underlined were “the prior version of our Subscriber Agreement will apply until [November 3, 2022]” and “Please visit our Help Center for more information about you subscription.” Finally, the email took the time to call out specific changes of note to the Subscriber Agreement – only four total – and one of those was an express update to the arbitration agreement….

Mr. Sadlock unambiguously manifested assent to the terms of the Subscriber Agreement….emails followed by continued use is sufficient to establish assent. Notably, the email explained to Mr. Sadlock that “these terms will be effective beginning on November 3, 2022.”

After stacking the inferences against Disney in the web formation process, the court stacks the inferences in favor of Disney with respect to these emails. Some of the dubious calls:

- The emails reference a “subscriber agreement,” but the court just held that the subscriber never knew that he was entering into a subscriber agreement. So when the emails say “we’re updating the agreement,” wouldn’t the reasonably prudent consumer be confused by that because they don’t think they have an agreement at all to be amended…? The court expressly addresses this, saying “There was undisputedly an agreement of some kind between Mr. Sadlock and Disney based on his purchase of the subscription service, even if there was no agreement to the terms contained in the Subscription Agreement (including the arbitration provision),” but this isn’t very satisfying, is it? How can Disney amend unknown terms?

- The layered notice here is viewed as a plus, not a minus.

- Another fetishization of underlining to signal hyperlinks, as opposed to the skepticism of offsetting font colors.

- The court accepts the subscriber doing absolutely nothing as “unambiguously manifesting assent.” This is especially shocking because the emails didn’t even have an express “call-to-action,” such as saying expressly that not cancelling = assent. In contrast, recall that the court said that affirmatively clicking on the “Agree and Subscribe” button didn’t unambiguously manifest assent to the terms, but here, doing nothing unambiguously manifests assent to the terms? WILD.

The court recognizes the potential havoc this ruling could cause and tries to mitigate the damage:

The Court is not opining that, in any instance in which a defendant sends an email giving notice of updated terms and a plaintiff continues to use the defendant’s service, the inquiry notice test has been satisfied. Indeed, the Court can see potential problems with a defendant relying on notice via email (problems aside from whether the email gave reasonably conspicuous notice of the terms of use). For example, was the email in fact received, or was the email shunted into a spam folder? Is there evidence that the plaintiff actually saw the email? On a macro level, what is the data on the likelihood that emails of this kind are actually received and opened by recipients under similar circumstances? The Court also notes that, should a defendant choose to give notice of updated terms via email, there are better ways to establish assent by the plaintiff instead of relying on continued use of the service. For instance, presumably, the email could ask the plaintiff to check a box contained in the body of the email, or to click a link contained in the email, confirming receipt of the notice and agreeing to the updated terms of use. There may be forensic tools to prove a particular email was received and opened by the recipient. By relying solely on the sending of an email and continued service without requiring the recipient to take some demonstrable affirmative step or proof of receipt and review, the proponent of the putative notice risks a finding of no constructive notice and assent. Emails present a different scenario that the situation where upon initial acceptance, the subscriber takes an affirmative step (e.g. clicking an “agree and subscribe” button) acknowledging receipt of notice. In this case, however, Mr. Sadlock has not contended he did not receive or see the emails in question and has made no argument presenting concerns such as those identified above.

If you have to add a disclaimer like this to your opinions, you probably should rethink the opinion.

If the plaintiff appeals this ruling, I could see the 9th Circuit affirming but on directly opposite grounds as this ruling, i.e., the web formation process was fine, the email amendment was not.

Sellers v. Bleacher Report, Inc., No. 23-cv-00368-SI. (N.D. Cal. July 28, 2023)

This is one of the seemingly infinite number of Facebook Pixel cases. Bleacher Report invokes the class action waiver in its TOS, which it purportedly added by amendment. The plaintiff agreed to the TOS in 2007, and the TOS said that Bleacher Report could amend the TOS by providing notice.

Bleacher Report claimed it provided user notice of the amendment via an email. The court disagrees: “The subject line of the email indicates content unrelated to the update notice….More significantly, the email shows no recipient in the “To:” field, so there is no evidence it was sent to anyone, much less that plaintiff received it.”

What does the court want to see in the “to” field…? Bleacher Report couldn’t have put millions of user emails into the “to” field–that would have been a privacy failure and would have led to a truly legendary “reply all” fiesta. Then again, Bleacher Report should have presented the court with sufficient and credible evidence about the email recipients to satisfy the court’s curiosity. As usual, a reminder: if you aren’t retaining evidence of who and how TOS amendments are being communicated in a way that can resolve the court’s evidentiary concerns, you are doing it wrong.

Bleacher Report also argued that it provided users with notice of amendments in 2016, 2020, 2022, and 2023 via interstitial popups onsite. Interstitial popup notifications are generally better than industry-standard amendment notifications and pretty close to gold standard practices for TOS amendment, so it seemed like Bleacher Report should be in good shape. Instead, anarchy ensues.

Bleacher Report submitted Wayback Machine URLs to the court to show how its popups worked. Say what? Bleacher Report should have kept its own evidence. If it wanted to be airtight, take a video showing the windows popping up and how there was no way for users to bypass the popup without clicking through. Instead, Bleacher Report is relying on the Wayback Machine for its evidence??? Among other problems, page elements aren’t always properly indexed on the Wayback Machine, so it’s not guaranteed to reflect the actual user experience. The court says that the 2020 Wayback Machine page doesn’t show the popup, so that creates an evidentiary uncertainty that delays resolution of the legal point. Ugh.

The 2016 Wayback Machine page did display the popup, but the court says “the pop-up was unobtrusive and the Court was able to access the website without clicking through.” Double UGH. A video would have been infinitely better evidence than the Wayback Machine page. Because the popup wasn’t a mandatory clickthrough, the court treats it like a browsewrap (“the notice was buried at the bottom of the page and did not prevent the user from accessing the site. Plaintiff was not required to affirmatively acknowledge the agreement in any way”). I’d need to see the implementation to understand why the court denigrates it so much, but this is also another unforced error by Bleacher Report. If you’re doing an interstitial popup to amend the TOS, display it loud and proud.

Kass v. PayPal, Inc., No. 22-2575 (7th Cir. July 27, 2023)

Kass created a PayPal account in 2004. The TOS contained a non-mandatory arbitration clause and said that PayPal could amend the TOS by posting notice on its site. It also said “the Agreement “and any other agreements, notices or other communications regarding your account and/or your use of [PayPal] … may be provided to you electronically,” either “posted on the pages within the PayPal website and/or delivered to your e-mail address.”” In 2012, PayPal added a mandatory arbitration clause that users could opt-out-of. PayPal employees declared that PayPal posted the amended TOS to its website and sent email notice of the amendment to its users.

The court notes, however, that “PayPal does not have a more specific record of sending that email notice to Kass or whether it was received, bounced back, or disappeared into cyberspace.” Uh oh. “By sworn declaration, Kass testified that she had never seen the amended User Agreement posted to PayPal’s website, that she did not receive an email notifying her of the amendment, and that she had never seen, known of, or agreed to the 2012 User Agreement with its mandatory arbitration clause.”

The court frames this as a mailbox rule problem. The court goes through the standard crusty common law principles: “Where a communication is shown to have been properly sent, Illinois law presumes that it was received,” but that’s a rebuttal presumption. The court says that PayPal properly showed its standard practice, but Kass’ denial casts enough doubt on the question to force a trial where a “trier of fact must therefore weigh PayPal’s evidence of custom and practice against Kass’s denial of receipt and determine whether Kass should be charged with having received notice of the arbitration amendment.”

The court sidesteps the obvious concern that plaintiffs can always represent that they didn’t receive the notice and thereby force a trial on the formation question. This legal standard ensures lots of meritless litigation. PayPal pushed back that Kass’ denial was potentially bogus, and the court clapped back “There is nothing conclusory about such a factual denial.” I disagree. [See what I did there?]

What blows my mind is that the court treats this as a first-principles question of common law. HELLO UETA and E-SIGN. For example, Section 15 of UETA (which Illinois adopted) specifies that an electronic record is received “when (1) it enters an information processing system that the recipient has designated or uses for the purpose of receiving electronic records or information of the type sent and from which the recipient is able to retrieve the electronic record; and (2) it is in a form capable of being processed by that system.” E-SIGN is a little less definitive, but it says that “The legal effectiveness, validity, or enforceability of any contract executed by a consumer shall not be denied solely because of the failure to obtain electronic consent or confirmation of consent by that consumer in accordance with paragraph (1)(C)(ii),” which says the consumer “consents electronically, or confirms his or her consent electronically, in a manner that reasonably demonstrates that the consumer can access information in the electronic form that will be used to provide the information that is the subject of the consent.” I’m not sure if these rules change the analysis or outcome, but they are relevant to any discussion of the “mailbox rule” to email. Yet the terms “UETA” and “E-SIGN” didn’t come up at all in the court’s opinion. Baffling.

In any case, the court summarizes its conclusion: “Whether she was subject to mandatory arbitration under the 2012 User Agreement depends on whether Kass received an email from PayPal notifying her of that amendment. This is a question of fact that must be resolved by a trier of fact, not summarily by the court considering only the paper record.”

How can you get around this court’s approach for TOS amendments ? Well, ditch email notifications and instead do things like popup notifications…but do the popups better than the Bleacher Report did, and keep better evidence.

[Note: the author of the Kass opinion, Judge Hamilton, also authored the terrible Salesforce opinion I will blog soon. Based on these two opinions, I surmise that Judge Hamilton goes out of his way to help plaintiffs, even if it requires twisting or ignoring legal precedents.]

* * *

BONUS: Some items from my unreasonably delayed 2023 quick links queue:

* Schneider v. YouTube, 3:20-cv-04423-JD (N.D. Cal. Jan. 5, 2023): “The TOS are not procedurally unconscionable in any meaningful way. To be sure, the TOS are adhesive and Schneider had no opportunity to negotiate their terms, but that is a minor degree of procedural unconscionability…. Schneider has not demonstrated that she had no “reasonably available” alternatives to creating a YouTube account, and consequently has not shown that the TOS are oppressive to the point of being procedurally unconscionable.”

* Doe v. Facebook, Inc., 2023 WL 3483891 (S.D. Tex. May 16, 2023). In a FOSTA case, court upholds Instagram’s TOS.

UPDATE: A rare discussion of E-SIGN, in a clickthrough case where the button said “acknowledge” instead of “agree”:

Zaccari’s “acknowledgment” is a signature for contractual purposes….Here, when Zaccari clicked the “Acknowledge” button, he engaged an “electric … process” that was “attached to or logically associated with” the Agreement and that falls within the expansive statutory definition of a signature. As the District Court concluded, Zaccari’s admission that he intended to click the “Acknowledge” button is necessarily also an admission that he intended to sign the Agreement; his engagement in that “electric process” is an “objective[ ] manifest[ation]” of his intent to be bound. Moreover, as a matter of common sense, Zaccari’s “acknowledgment” is meaningful evidence of his intent to be bound in this particular circumstance because clicking a button in this manner is a common method of contractual acceptance in the world of clickwrap software contracts—the kind of contract Zaccari could reasonably be expected to be familiar with given his substantial background in computer programming.

Apprio, Inc. v. Zaccari, 2024 WL 3076769 (D.C. Cir. June 21, 2024)