If “Trespass to Chattels” Isn’t Limited to “Chattels,” Anarchy Ensues–Best Carpet Values v. Google

Trigger warning: this is a terrible opinion. Let’s hope the judge corrects his errors or that the appeals court does it for him.

* * *

This opinion addresses a venerable issue in Internet Law: can a website control how visitors see its web pages? I first remember this issue flaring up in the late 1990s when Third Voice, a browser plug-in, let users write commentary “over” third-party websites. That sparked angst among website operators who couldn’t control what users were saying about them in the Third Voice frame. Third Voice was followed by adware vendors such as AllAdvantage, which framed third-party websites, displayed ads in the frame, and shared some ad revenue with users (its tagline: “Get Paid to Surf the Web”). Gator, WhenU, and other adware vendors followed. By its nature, adware changes the screen display of the sites users are visiting. A series of lawsuits from two decades ago covered some important ground regarding the ability of website owners to block adware. Wells Fargo v. WhenU concluded that copyright was a dead-end. 1-800 Contacts v. WhenU concluded that trademarks was a dead-end. Nevertheless, because adware often provided poor consumer experiences, adware largely fizzled out by 2010. As a result, the legal issues rarely are litigated any more.

* * *

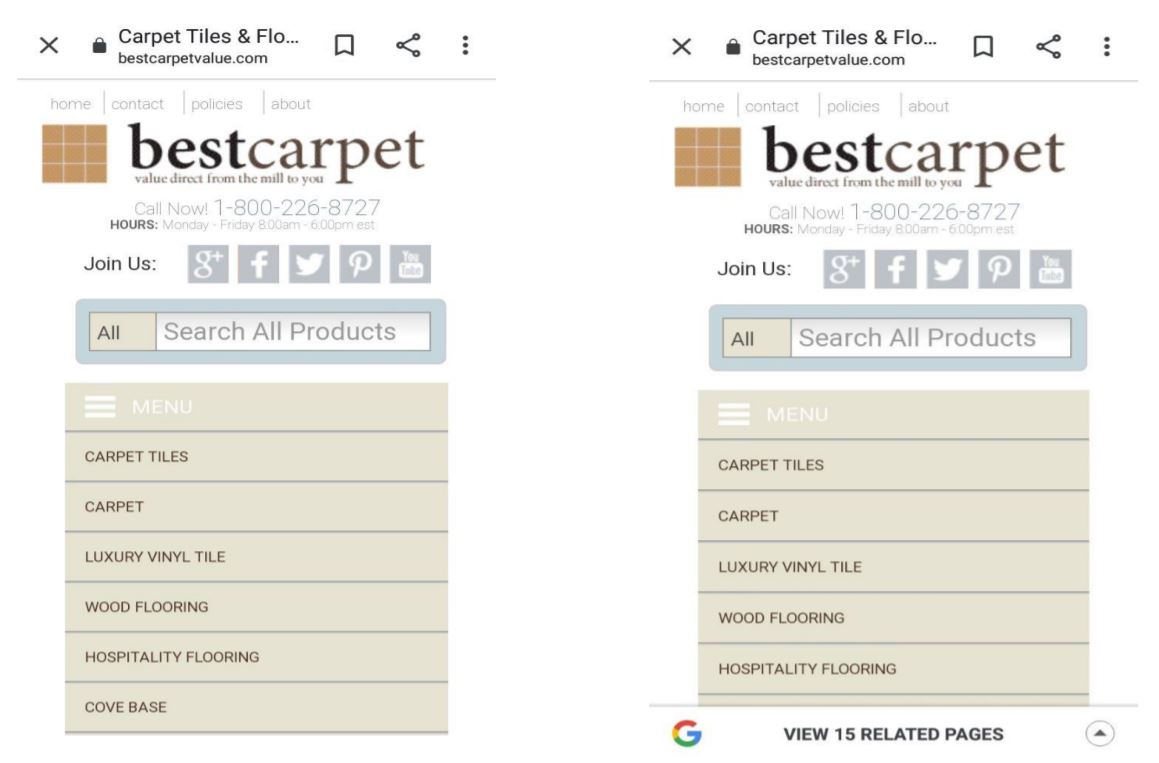

The court approaches this case like it’s an adware case, but the court never once uses the term. The issue is that Google incorporated a new feature into its Android software. You can see how it modified a website’s display in these before/after screenshots (the component at issue is the “view 15 related pages” bar on the bottom right):

The plaintiffs alleged that the prior screenshot contains ads, which turns this case into an adware case. But the screenshot doesn’t label the listings as “ads,” so either Google uncharacteristically cut that corner or these listings are organic search results, and this isn’t an adware case at all. I’m going to characterize Google’s feature as an “adware bar” because the court accepts the plaintiffs’ allegations as true on a motion to dismiss, but I wonder if that characterization will withstand further scrutiny.

Underlying this litigation is an epistemological question: what does a “canonical” version of a web page look like? Every browser software makes its own choices about how to render a page; every browser software “frames” every web page with its software features; and every browser software lets users configure the display in ways that affect website owners’ expectations. As just one example of the latter point, browser software programs let users magnify or shrink the display size, so what appears above/below the fold critically depends on user configuration, not just the website operator’s choices.

For this reason, if courts want to assess the veracity of the plaintiffs’ claim that the “cove base” link gets covered up, judges must assume how a canonical version of a web page appears. For example, in the “before” image above, the court doesn’t explain the source of the screenshot, what technological conditions it reflects, and how often those conditions will hold in the field. Thus, a court’s hypothesis may have no grounding in reality. It also strips users of their own agency to decide what browsing tools best serve their needs and how best to configure those tools.

* * *

In this lawsuit, the plaintiffs aren’t suing Google for violating their copyrights or trademarks. With respect to copyright, the court says: “Plaintiffs do not rely on copyright protection for their websites in pleading their claim…Plaintiffs are not asserting infringement of any right to the reproduction, performance, distribution, or display of their websites. Plaintiffs want and expect Google to copy and display their websites in Chrome browser and Search App, and acknowledge that Google has license to do so.”

Wait, what? We need to know more about this license. If a website “permits” browser software to display them (assuming such permission is even required in the first place, and assuming that permission isn’t automatically granted by connecting the website to the web), then a website can’t control the browser software configurations. It seems like this license could be dispositive to the case, but the court doesn’t explore it more.

Trespass to Chattels

The plaintiffs instead claim that the adware bar constitutes a trespass to chattels. However, Google’s adware bar never interacts with the plaintiffs’ physical servers at all. As the court says, “None of Plaintiffs’ websites, files, or data were physically altered in any way. Nor were Plaintiffs’ servers disrupted.” Instead, the adware bar’s display customization takes place solely on the user’s device, supplementing how the code renders on the device. So the “chattel” at issue here isn’t the website operator’s servers; it’s the HTML code that the website operators send to each user’s device (and gave Google permission to display).

If the “chattel” at issue is only the intangible HTML code, then no “chattels” are being trespassed. It’s not possible to “trespass” an intangible asset; any legal protection for the asset comes from contract law (but the plaintiffs gave a license) or IP law, such as copyright law, which the plaintiffs aren’t invoking. Thus, given that “intangible chattel” is a legal oxymoron, a lawsuit over “trespassing HTML code” should fail hard. It didn’t.

Citing a 2003 Ninth Circuit case, Kremen v. Cohen, the court says “a website can be the subject of a trespass to chattels claim.” This abstract statement requires more clarification. The Kremen case involved the alleged theft of the sex.com domain name by improperly modifying the electronic records evidencing ownership of the domain name. The Ninth Circuit held that the intangible asset (the domain name) could be “converted,” even though normally conversion only applies to chattel (i.e., physical property), not intangibles. We need legal doctrines to redress the improper hijacking of the monetary value of owning a domain name, just like we would redress the improper acquisition of monetary value stored in an online bank or cryptocurrency account. Thus, other cases have applied conversion law to alleged theft of domain name registrations (e.g., CRS v. Laxton).

But the Kremen case didn’t say that all of a website’s intangible assets are like tangible assets. If it had, it would have eliminated the distinctions between IP law and the law of chattels.

So when this court says “Plaintiffs have property rights to their websites for the same reasons a registrant has property rights to a domain name,” I have no idea what it means. A website can sometimes control access to its servers (see the Van Buren case). A website can own the copyrights to the HTML code and the files that users download. Website owners can prevent the unauthorized reassignment of their ownership interests, such as someone trying to modify their copyright registration records. But the broad statement “property rights to their websites” is mostly wrong.

To find the HTML code’s physicality necessary to treat it like a chattel, the court makes this garbled statement:

like a domain name, a website is a form of intangible property that has a connection to an electronic document. “A website is a digital document built with software and housed on a computer called a ‘web server,’ which is owned or controlled in part by the website’s owner. website occupies physical space on the web server, which can host many other documents as well.” Compl. ¶ 34. Plaintiffs’ website is also connected to the DNS through its domain name, bestcarpetvalue.com, just as Kremen’s domain name was connected to the DNS.

This is very, very confused. My copyrighted works may be printed on physical pages, but that doesn’t mean a third-party’s encroachment into my intangible copyrights becomes trespass to chattels. That’s the purview of copyright–or not restricted at all. And the linkage to the domain name record is nonsensical because the domain name wasn’t “taken,” and indeed the website operator gave a license to display it. The court even acknowledges that its line of logic has been rejected before:

After Kremen, the California Court of Appeal, Sixth Appellate District, noted that conversion traditionally required a taking of tangible property and that “this restriction has been greatly eroded,” but not “destroyed.” Silvaco Data Sys. v. Intel Corp., 184 Cal. App. 4th 210, 239 n.21 (2010). The Silvaco court also cautioned that “the expansion of conversion law to reach intangible property should not be permitted to ‘displace other, more suitable law.’” As discussed above, however, Plaintiffs’ websites have a connection to a tangible object.

Having accepted the core fallacy of the plaintiffs’ claims, the court makes unhelpful statements like “trespass to chattels ought to apply to a website, and several courts have so found.” The first half of the sentence isn’t in contention; everyone agrees that trespass to chattels can protect a website’s servers (not at issue in this case). Some of the cited precedent do not involve applying trespass to chattels only to intangible code. Some courts have in fact done this (not all of which the court cited), but those cases are overwhelmed by precedent rejecting the point. The court disregards Google’s citations those cases, breezily saying “Other cases cited by Google do not discuss the distinction between tangible and intangible property and offer little guidance.” (That critique might apply to this opinion, too).

Having satisfied itself that “a website is a form of intangible property subject to the tort of trespass to chattels,” the court next turns to harm. The court ignores the plainly stated and impossible-to-miss holding of Intel v. Hamidi, which says that common law trespass to chattels is actionable only when electronic signals cause or threaten to cause measurable loss to computer system resources. The plaintiffs can’t possibly prove any harm to any computer system resources.

Instead, the court cites a different part of the Hamidi opinion saying that Intel didn’t show any “physical or functional harm or disruption” to its computer systems. The court proceeds: “although Plaintiffs are not alleging physical harm to their websites, they do allege functional harm or disruption.” HOLD ON. The plaintiffs may claim “functional harm or disruption,” but the complete test is functional harm or disruption…TO THEIR COMPUTER SYSTEMS. By omitting those words, the court dramatically and improperly expands the test. Seriously, it’s impossible to read the Intel v. Hamidi opinion and miss the majority’s point that not all intangible harms count; only harms to COMPUTER SYSTEM RESOURCES count.

The court says the plaintiffs sufficiently alleged “functional disruption” by claiming that Google’s ads “obscured and blocked their websites, which if true, would interfere with and impair their websites’ published output. Although Google’s ad may not have disabled or deactivated the ‘Cove Base’ product link, it nevertheless allegedly impaired the functionality of the website: an Android phone user cannot engage a link that cannot be seen.” But “published output” isn’t a computer system resource, and an “obscured link” assumes what the hypothetical canonical website looks like.

Implied-in-Law Contract/Unjust Enrichment

Given that the plaintiffs granted a license to Google to display its site, I don’t know what this claim could possibly cover. Google responds that whatever it means, it’s preempted by copyright law. Google’s position seems reasonable given that this claim wades squarely into copyright’s realm. The adware cases from 2 decades ago rejected copyright claims in virtually identical facts; and there are the old copyright cases involving things like adding ads to pre-manufactured videos. Not surprisingly, this judge finds a way around that too.

The court summarizes that “Google allegedly covered up or obscured a portion of Plaintiffs’ websites from Android phone users for financial benefit, which makes their claim ‘qualitatively different’ from a copyright claim.” No, that’s exactly what the derivative work right covers, and it’s the exact issue litigated in the old WhenU cases. To get around this, the plaintiffs argued:

Google could not in the brick-and-mortar marketplace lawfully plant its logo on Plaintiffs’ storefront windows without Plaintiffs’ consent, even if Google owned their buildings. Nor could Google place ads in Plaintiffs’ marketing brochures or superimpose ads on top of Plaintiffs’ print advertisements without Plaintiffs’ permission and without paying Plaintiffs’ price. Likewise, Google cannot in the online marketplace unilaterally superimpose ads on Plaintiffs’ website without Plaintiffs’ consent and without compensation just because Google makes the software through which Android users view that website on their mobile screens…

a storefront business owner is injured when its window is obscured, regardless of whether that window is clear or covered with advertisements. By analogy, a website owner is injured when its website is obscured by unwanted ads, regardless of the content displayed in the website.

Are we really doing this again? I agree Google can’t unilaterally stick its logos onto a physical retailer’s windows…because THAT WOULD BE REAL PROPERTY TRESPASS. I’m not sure what law prevents Google from placing ads over marketing brochures or print ads OTHER THAN COPYRIGHT LAW (or possibly trademark law–but at this point, what does any of this have to do with IMPLIED-IN-LAW CONTRACTS?). And there are many other forms of competitive marketing adjacencies that are fully permissible in the offline/physical space world, as I documented over a decade ago in my Brand Spillovers paper.

Plus, let’s not lose sight of the users’ agency–they are the ones responding to the marketing signals. They aren’t passive automatons in this equation. My Deregulating Relevancy article from 15 years ago explains that principle more.

First Amendment

There is some discussion about the First Amendment, but it’s so terrible that I can’t bring myself to blog it. To summarize: the court seems to be saying that the plaintiffs can suppress truthful non-misleading advertising without relying on any intellectual property rights (and without any countervailing public policy doctrines, like fair use). That can’t possibly be right.

Implications

As you can see, the court creates a distorted pastiche of the precedent to reach an obviously wrong and wholly counterintuitive outcome.

In particular, the court’s mangled summaries, like “Plaintiffs have property rights to their websites” and “a website is a form of intangible property subject to the tort of trespass to chattels,” cannot survive critical scrutiny. What is the point of calling it “trespass to CHATTELS” if no actual chattels are harmed? In that circumstance, the trespass to “chattels” doctrine becomes a boundary-less “commercial trespass to intangibles” concept that both lacks any precedent and conflicts with the entire system of IP.

A boundary-less commercial trespass doctrine creates plenty of problematic edge cases:

- By design, ad blockers block portions of how websites display. (The websites can’t claim copyrights in third-party ads, but this court wasn’t considering copyright anyways). How would the court’s “commercial trespass” doctrine apply to ad blockers? Indeed, unlike Google’s browser software, many websites expressly contractually ban ad blockers.

- What about updates of browser software? By definition, those updates change the previous website renderings to a new website rendering. If any website prefers the old rendering to the new, can it sue the browser software for commercial trespass?

- Browser software programs allow users to resize their windows. Commercial trespass?

- Phone manufacturers create different screen sizes. If this cuts off “cove base” from being above the fold, liability?

This case brought to mind the Edible Arrangements v. Google lawsuit in Georgia (also not cited by the court). In that case, the trademark owner claimed that Google committed theft/conversion by selling its trademark for keyword advertising purposes. Unlike this court, the Georgia appellate court rejected the theft/conversion analysis. Weirdly, though, the Georgia Supreme Court granted a petition to hear the case, so who knows anything any more?

Case citation: Best Carpet Values Inc. v. Google LLC, 5:20-cv-04700 (N.D. Cal. Sept. 24, 2021)