The Ninth Circuit’s Confusing Ruling Over Snapchat’s Speed Filter–Lemmon v. Snap

The Facts

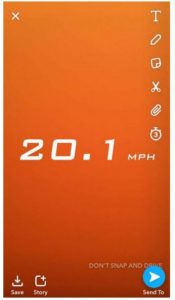

Two of the boys’ parents sued Snapchat for defectively designing its speed filter. The district court dismissed the case on Section 230 grounds, saying: “Plaintiffs are seeking to hold Defendant responsible for failing to regulate what the users post through the Speed Filter; if the users were not motivated to capture their high speeds for content, they would not speed.”

In other words, the court treated the speed filter as a content scripting tool that facilitates content publication. There isn’t any other credible use case. Theoretically, users could make snaps using the speed filter for their personal enjoyment without ever sharing them, but who would do that? Because the speed filter produces content that third parties will publish, the district court concluded that Section 230 applied to lawsuits over its (mis)use.

The Ninth Circuit’s Ruling

The Ninth Circuit disagrees. The court applies the familiar 3-part test for a Section 230 defense.

ICS Provider. “the Snapchat application permits its users to share photos and videos through Snap’s servers and the internet. Snapchat thus necessarily ‘enables computer access by multiple users to a computer server.'”

Publisher or Speaker. The court says the lawsuit doesn’t seek to hold Snapchat liable as a publisher or speaker:

Their negligent design lawsuit treats Snap as a products manufacturer, accusing it of negligently designing a product (Snapchat) with a defect (the interplay between Snapchat’s reward system and the Speed Filter). Thus, the duty that Snap allegedly violated ‘springs from’ its distinct capacity as a product designer. This is further evidenced by the fact that Snap could have satisfied its ‘alleged obligation’—to take reasonable measures to design a product more useful than it was foreseeably dangerous—without altering the content that Snapchat’s users generate. Snap’s alleged duty in this case thus ‘has nothing to do with’ its editing, monitoring, or removing of the content that its users generate through Snapchat.

The court adds that the “duty to design a reasonably safe product is fully independent of Snap’s role in monitoring or publishing third-party content,” but in a footnote, the court clarifies that “the Parents do not fault Snap for publishing that photo message,” and Section 230 would apply to any claims that other users’ snaps induced irresponsible driving.

The court is navigating a fine line. The court says the harm took place irrespective of whether any content published at all, but the court disregards the speed filter’s sole purpose as a content authoring tool. Furthermore, because Section 230 would apply to claims about outputted content, this opinion wouldn’t change cases like Herrick v. Grindr, where third-party content (the fake postings) caused the harm. The court emphasizes this point: “Those who use the internet thus continue to face the prospect of liability, even for their ‘neutral tools,’ so long as plaintiffs’ claims do not blame them for the content that third parties generate with those tools” (emphasis added).

The plaintiffs made a key admission by not suing over any of the photos/videos made using the speed filter. That became the hook for the appeals court to reverse the district court. However, it also substantially reduces the applicability of this ruling in future cases, because most plaintiffs will want to impose liability for published content.

Third-Party Content. Because the parents disclaimed any liability based on the snaps posted by their children, “the Parents’ negligent design claim [is] standing independently of the content that Snapchat’s users create with the Speed Filter….the Parents’ claim does not depend on what messages, if any, a Snapchat user employing the Speed Filter actually sends.”

By saying Snapchat failed on two of the three elements of a Section 230 defense, the court gave plaintiffs two different ways to challenge Section 230.

Implications

Ninth Circuit Schizophrenia About Section 230. The Ninth Circuit’s Section 230 jurisprudence vacillates from case to case. Some rulings impose key limits to Section 230; other rulings are among the most 230-favorable opinions in the country–such as its important Dyroff v. Ultimate Software ruling that Internet services aren’t liable for recommending or amplifying illegal content, which remains good law and substantially limits this ruling. Some of its schizophrenia comes from the Ninth Circuit’s large size. Panel composition varies widely and can create a whipsaw effect. As a result, it’s hard for any single Ninth Circuit Section 230 opinion to represent a watershed change. Who knows what the Ninth Circuit will do in its next 230 decision?

Restating the Holding. The opinion says that Section 230 doesn’t preempt a design defect claim only if the claim doesn’t depend on third-party content. If the plaintiff’s goal is to reach third-party content, Section 230 still applies. That makes sense. For example, a data security breach claim isn’t preempted by Section 230, even if it’s a third-party malefactor stealing third-party content. Indeed, a Georgia Appeals Court previously reached the same conclusion regarding Snapchat’s speed filter.

Still, the court’s wording will spur troublesome future lawsuits. In these hypotheticals, does Section 230 apply? Should it?

- Assume YouTube created an Urbexing video category and a property owner sued YouTube for encouraging its users to trespass to make their videos.

- Assume a business sued eBay for employee theft because eBay knows that some employees resell their employers’ stolen equipment on eBay. The theft occurs even if the employee never lists the product on eBay.

- Assume a TikTok user injures himself and a third-party bystander while making a video doing a dangerous stunt and alleges that TikTok encourages dangerous stunts because those videos garner more views, but never posts the video. (TikTok knows users post dangerous stunt videos because it slaps a warning label on them).

Strawmen Arguments. The opinion repeats the same strawmen argument at least three times:

- “our case law has never suggested that internet companies enjoy absolute immunity from all claims related to their content-neutral tools.”

- “[t]he [CDA] was not meant to create a lawless no-man’s-land on the Internet” (from Roommates.com).

- ““Congress has not provided an all purpose get-out-of-jail-free card for businesses that publish user content on the internet” (from Internet Brands).

All three quotes rely on the same fallacy that Section 230 preempts ALL claims, but Section 230 statutorily excludes four categories of claims (federal criminal prosecutions, IP, ECPA, and FOSTA). Section 230 has never created “absolute” immunity or a “lawless/”get-out-of-jail-free” zone, and that’s clear to anyone who reads the statute. These statements are so obviously mockable that they should never appear in a court opinion again. Do better, judges.

The opinion’s beginning is also a lowlight: “In 1996, when the internet was young and few of us understood how it would transform American society, Congress passed the CDA.” Well, Section 230’s drafters understood the Internet’s transformative potential.

The Plaintiff Probably Won’t Win on Remand. In Maynard v. Snap, the Georgia Appeals Court held that Snapchat wasn’t liable for the speed filter-related car crash because it didn’t have a “special relationship” with the innocent bystanders. In this case, Snapchat had a contract, but not special, relationship with the deceased boys. So the Georgia result suggests this case will probably also fail on its merits.

If so, this opinion sets up plaintiffs to spend more time and money on litigation to no avail. This highlights one of Section 230’s most important procedural benefits. If a case will lose, everyone benefits when it loses earlier.

If the plaintiffs lose on remand, this will be at least the third time the Ninth Circuit messed up Section 230 without benefiting plaintiffs. First, the Roommates.com ruling created new common law exceptions to Section 230, but the Ninth Circuit held (four years later) that the defendant never violated the law. Second, in Internet Brands, the court held that failure-to-warn claims aren’t covered by Section 230, but the defendants never had a duty to warn (same outcome in Beckman v. Match.com). I sense a redux.

Obviously, plaintiffs love the opportunity to get around Section 230. But between the court’s narrow holding and the high likelihood that plaintiffs’ design defect claims will fail even if they get around Section 230, this ruling looks more like typical Ninth Circuit jurisprudential melodrama than a major precedent.

Case citation: Lemmon v. Snap, Inc., 2021 WL 1743576 (9th Cir. May 4, 2021)