Lime’s User Agreement Sends Another Case to Arbitration–Babcock v. Neutron

This is another personal injury lawsuit against Lime for e-scooter rentals. You do know that rent-a-e-scooters are death sticks, right? Lime invoked the arbitration clause in its User Agreement. As usual, the key question is: was the User Agreement properly formed?

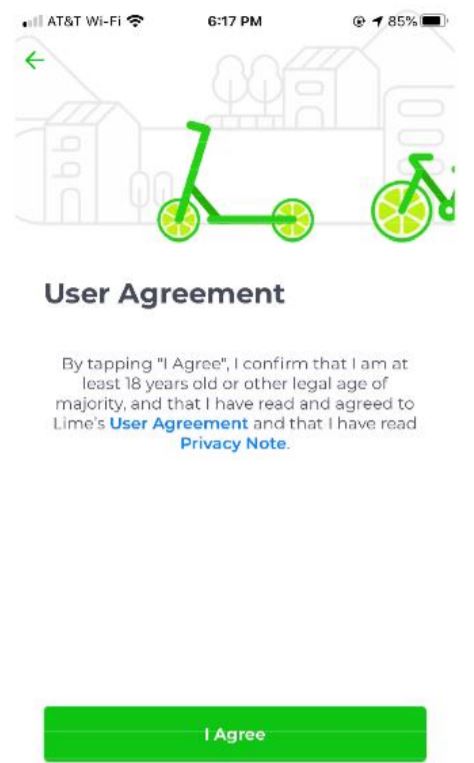

The contract formation UI at issue in this case:

The court explains: “If the user dares to inquire into the full terms of the User Agreement, the user can tap the “User Agreement” hyperlink, which takes the user to a webpage containing the full terms.” If…you…dare… The User Agreement contained standard provisions binding users to arbitration and specifying California as the governing law.

The court says that Lime’s implementation is a “sign-in-wrap” (UGH) that consumers should be familiar with:

Across the country, consumers use their smartphones every day to follow the news, to shop, to online bank, to research health conditions, to play games, and to participate on social networking platforms. Consumers also routinely use smartphone applications for ride-hailing services like Uber and Lyft; and more recently, consumers are using applications for other mobility services, such as to rent e-bicycles and e-scooters through companies like Lime. In short, contracting for services on smartphone applications is now commonplace in the American economy….

the Court finds that the blue boldface hyperlink to the User Agreement’s terms (where the user could read the full Arbitration Provision), combined with the unambiguous warning that “[b]y tapping ‘I Agree,’” the user confirms that he or she “read and agreed to Lime’s User Agreement,” is conspicuous enough to put a reasonably prudent smartphone user on inquiry notice of the Arbitration Provision….

Taken together, the large black boldface User Agreement title, the non-bold black User Agreement acknowledgement, the blue boldface User Agreement hyperlink, and the lime-green “I Agree” confirmation button create a user friendly display. The assortment of contrasting colors, and bold and non-bold fonts, combine with empty white space to visually separate each piece of information so that the user clearly understands that by tapping “I Agree,” he or she is agreeing to be bound by the User Agreement’s terms, which are readily accessible by tapping on the blue boldface hyperlink.

The court notes that numerous other courts have held that “‘sign-in wrap’ agreements like Lime’s agreement provide consumers with sufficient notice of arbitration provisions.”

So what did Lime do right here? As the court notes, the screen made appropriate use of fonts, colors, bolding, and titles. That all helped. The screen contained a proper call-to-action and placed it above the “I agree” button, and that surely helped too. Most importantly, Lime gave the user agreement its own dedicated screen, which I think is a powerful step towards contract formation. There’s no other raison d’etre for the page to exist; and courts are likely to give that credit. Thus, although there is only 1 click on this particular screen, I think the standalone screen in the page flow will get as much credit in court as a second click would.

I recently blogged another successful arbitration request for Lime (Walker v. Neutron). That case involved a different UI that honestly was legally dicier. Nevertheless, that court also deemed that screen a “sign-in-wrap” (UGH) and upheld it too. I suspect today’s case involves a more modern UI implementation by Lime; if so, they should feel comfortable that they are moving in the right direction.

Case citation: Babcock v. Neutron Holdings, Inc., 2020 WL 1849405 (S.D. Fla. April 13, 2020)

BONUS CONTENT:

In Cristales v. The Scion Group LLC, 2020 WL 1888982 (D. Ariz. April 16, 2020), a landlord sent marketing text messages to tenants. The tenants had entered into a TOS with an arbitration clause, which the landlord invoked. Among other arguments, the tenants argued that the contract was illusory because of its amendment clause. The TOS says:

you are bound by the version of this Agreement that is in effect on the date of your visit. This Agreement may change from time to time, so please review it when you visit the Site.

For reasons that aren’t clear to me, the court says this language does not permit the landlord to make unilateral changes. Instead, the court says that any amendments require tenant assent. As construed, the court says this provision is valid. Cite to Brittain v. Twitter.

The plaintiffs also criticized “use of a ‘clickwrap’ agreement which requires a consumer to click on an optional hyperlink to review the agreement.” But “[c]lickwrap agreements are increasingly common and have routinely been upheld.”

__

Another contract ruling in a text message marketing case: Ford v. Netgear, Inc., Case: 216-2019-CV-00704 (N.H. Superior Ct. March 9, 2020). A law professor will have to arbitrate his dispute due to the TOS arbitration clause. The court calls the TOS a “hybrid” between clickwrap and browsewrap (UGH), but it was still enforceable because:

Right above the “register” button on Netgear’s webpage is a text box stating: “I understand by pressing ‘register’ my information will be used as described here and in the Privacy Policy and I agree to the Terms.” The phrase “Privacy Policy” and the word “Terms” are both in bold text. An average reasonable person would know that he was agreeing to the Terms and Conditions by clicking on the “register” button and that the bold word “Terms” was a hyperlink. The Court also notes that the plaintiff, “a law professor who teaches and writes about internet law, privacy law, cybersecurity, and other issues involving technology and the law,” is in an even better position than an average person to understand the implications of clicking the “register” button on Netgear’s webpage.