No “Contract By Tweet” for Plaintiff Who Pitches Movie Idea via Social Media

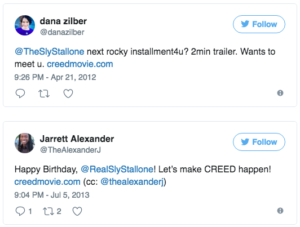

Jarrett Alexander alleged that he came up with the idea for Creed, drafted the screenplay, and put together a pitch reel that he initially posted on Vimeo and then on a separate website. He also alleged he circulated the idea and the pitch reel to various industry types, including those associated with the original Rocky movies. He also tried to raise awareness for the idea on social media by promoting the idea on Twitter. Plaintiff and his friends tweeted at The Rock (who is friends with Stallone), to Carl Weathers (who played Creed in the Rocky movies) and to Sylvester Stallone himself. The complaint did not allege that any recipients acknowledged the tweets or took action based on them. Sometime later, MGM and Stallone announced their plans to develop Creed, which plaintiff alleges bears thematic similarities to plaintiff’s own idea.

Misappropriation of idea claim: the court says this tort is recognized in certain narrow situations and requires either confidentiality or a contractual promise. An idea itself is not protectible. Confidentiality is obviously not available given public dissemination of the idea. The court thus looks to the second possibility.

Implied contract: The court says an implied contract claim requires plaintiff to show that he prepared the work and offered it to defendants under circumstances that would reasonably be understood to require compensation upon use of the work (i.e., he needed to satisfy the typical elements of contract formation). The court is skeptical that plaintiff’s tweets satisfy this standard. Plaintiff falls back on custom of the industry and says he understood based on industry custom that he would be compensated. The court says this theory fails as well:

while requiring an in person meeting for misappropriation of idea claim in the world of movie and television pitching may be unrealistic in light of communication and social media advancements, plaintiff’s theory of implied contract by tweet and by mass-mailing of the screenplay might turn mere idea submission into a free-for-all.

The court identifies other problems with the plaintiff’s theory as well (1) he doesn’t identify any terms that he appended to the submission, and (2) he cites to no exchange whatsoever with the defendants in which terms were discussed. The court also cites to a widely-cited appropriation case:

the idea man who blurts out his idea without first having made his bargain has no one but himself to blame for the loss of his bargaining power. The law will not in any event, from demands stated subsequent to the unconditioned disclosure of an abstract idea, imply a promise to pay for the idea…

Unjust enrichment claim: The court cites to similar flaws and dismisses his unjust enrichment claim.

___

We haven’t seen many idea submission cases where an idea is submitted over social media. While in a totally different context, and a unilateral contract case, this case reminded me of the YouTube rewards case, where the court said a rewards offer broadcast on YouTube was an offer that could be accepted by performance: “A Reward Offer Still An Offer, Even if It’s Made on YouTube – Augstein v. Ryan Leslie“.

The court recognizes all sorts of mischief that could be wrought by recognizing these types of claims absent some sort of acknowledgment from the defendant(s). It would have been interesting to see what the result would have been if Carl Weathers, the Rock, or Stallone responded to the tweets in some way (such as by faving or retweeting, or responding). A gesture such as that is probably innocuous and would not have moved the needle on this claim, but the absence of such a gesture made the case particularly easy.

The court flagged that while an idea misappropriation claim is not recognizable without confidentiality or some contractual hook, standing on its own, it’s also preempted by copyright. This made me wonder whether plaintiff considered this route. Not that it would have been meritorious, but since the plaintiff asserted a slew of other claims you’d think he would have thrown it in as well.

This case was a long shot at best, made intriguing only by the alleged similarities between plaintiff’s idea and the movie ultimately developed by Stallone & co.

___

Eric’s Comments:

1) I think the world would be a better place if we permanently eliminated any “idea submission” doctrines. I’m fine with other torts applying if the requisite elements are met, such as trade secrets, contract law or copyright law. However, a standalone “idea submission” doctrine is invariably unmeritorious–and pernicious.

2) This is not Stallone’s first time being sued for using someone’s movie ideas related to the Rocky character. Some IP Survey casebooks, including the Merges, Menell, and Lemley book, include the Anderson v. Stallone ruling over Rocky IV. In that case, Stallone was quoted in the press describing his vision for Rocky IV (remember, the one with Dolph Lungren, the killer Russian robot?), Anderson incorporated those ideas into a treatment he wrote on spec, Anderson pitched the treatment to studio executives and eventually Stallone but made no sale, then he sued for copyright infringement based on the similarities between the treatment and the movie. The court held that Anderson never had a copyright license to create a derivative work, the treatment was a derivative work of the Rocky characters, and Anderson didn’t have any copyrights to the unauthorized derivative work. The net effect of the court’s ruling is that Stallone could freely take whatever he wanted from Anderson’s treatment. Assuming this is good law, this still leaves open the strange pattern that the Rocky sequels have produced two completely independent lawsuits that Stallone “borrowed” from others. Maybe this is just coincidence…

___

Case citation: Alexander v. MGM, CV 17-3123-RSWL-KSx (C.D. Cal. Aug. 14, 2017). The initial complaint

Related posts:

* A Reward Offer Still An Offer, Even if It’s Made on YouTube – Augstein v. Ryan Leslie

* Appeals Court: Accepting Lawyer’s Prove-me-Wrong Challenge Does not Form a Contract

* Court Rules That Instant Message Conversation Modified the Terms of a Written Contract — CX Digital v. Smoking Everywhere

Pingback: CLIP-ings: September 15, 2017 – CLIP-ings()