Consumers Who Don’t Read “Clickwraps” Are Still Bound By Them–Toth v. Everly Well

Raise your hand 🙋♂️ if this could describe you too:

Joyce Toth clicked on a checkbox indicating that she read and accepted certain terms and conditions, which were contained in a linked “User Agreement.” Her representation was only half true. Toth, like countless consumers before her, did not read the terms and conditions that she ostensibly accepted.

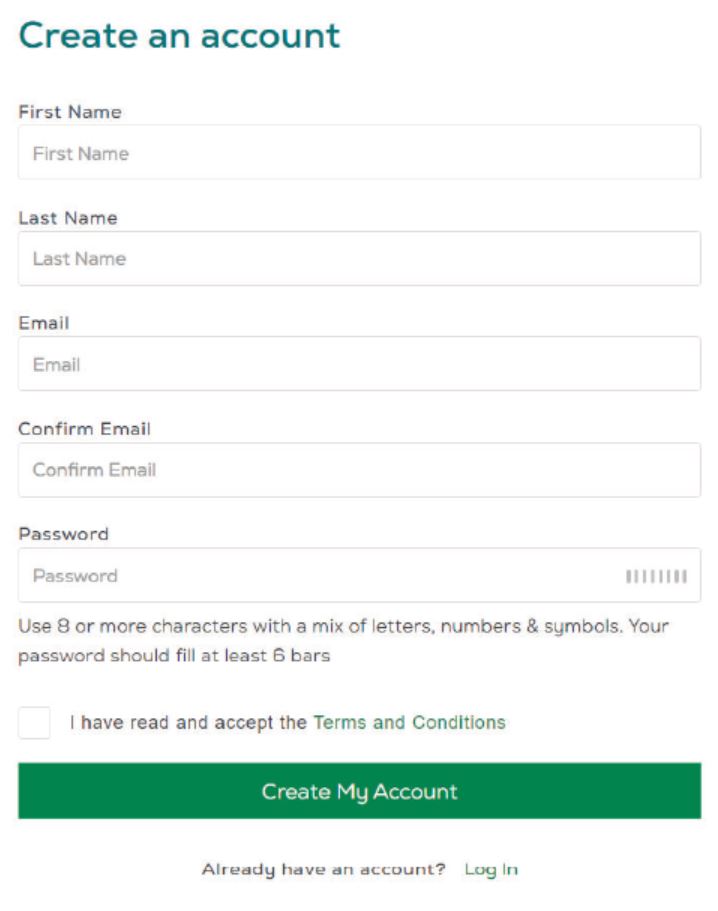

The vendor in this case sells food sensitivity kits. Consumers buy a physical kit, but then need to create an online account to get the results. The court doesn’t include a screenshot of the online TOS formation process. Instead, it describes it textually:

The account-creation page on its website asks users to input some basic information and then click a checkbox indicating that they “have read and accept the Terms and Conditions[.]” The phrase “Terms and Conditions” is highlighted in green font and embedded with a link. The checkbox and accompanying text are located directly above the “Create Account” button, and a user cannot register a kit without first clicking the checkbox.

This screenshot is from a declaration by the defendants:

(Note that the checkbox lacks an if-then call-to-action and isn’t tied to the “create my account” button–minor and tendentious details that could nevertheless have given judges some pause. The mandatory nature of the checkbox partially fixes that discrepancy).

The TOS contained an arbitration clause that the defendants seek to invoke.

The named plaintiff purchased a physical kit and then navigated through the online account creation process, including clicking on the checkbox. The putative class action claims that the tests produce bogus results.

The court characterizes the formation process as a “clickwrap,” which the court says usually create binding contracts. That’s the case here.

First, the consumer had proper notice of the terms due to the checkbox. The consumer said she didn’t read the terms, but she was on inquiry notice. The consumer pointed to the Kauders precedent from the Massachusetts Supreme Court. This court responds that Kauders “did not conclude that an online-service contract could never notify a customer of an arbitration provision. It merely clarified that the unique nature of online-service contracts requires courts to ‘carefully consider the interface and whether it reasonably focused the user on the terms and conditions.'” Here, “Everlywell’s terms and conditions are far more conspicuous than those in the putative contract at issue in Kauders.” Thus, “A reasonable user would understand that the terms and conditions on Everlywell’s site applied to use of the test kit.”

Second, the checkbox “secured meaningful assent.” The consumer said that she formed the contract with Everlywell when she bought the physical kit. However, the court says “the box containing the test Toth purchased stated on its exterior that ‘[p]urchase, registration, and use are subject to agreeing to the Everlywell User Agreement, which can be read at everlywell.com/terms[.]'” Apparently that’s enough to put her on notice of the additional terms that either were incorporated into the original contract or remained subject to separate formation. “Thus, Toth has failed to show that Everlywell owed a pre-existing obligation to her and thereby failed to show that Everlywell coerced her assent by threatening non-performance.” The court summarizes:

Had Toth sued Everlywell before creating an account, her case would present an intriguing assent question: Did Toth effectively accept the User Agreement by buying and using the test without attempting to return it? Instead, her case presents a much more straightforward question, easily answered by Toth’s admission that she clicked the checkbox.

The court rejects the buyer’s other arguments:

- She claimed the unilateral modification provision made the contract illusory. The court says that argument was rejected in the 2021 Handy precedent.

- The court rejects the unconscionability challenge. “Toth identifies many allegedly one-sided provisions in the dispute-resolution section of the User Agreement, but none make the delegation provision itself unfair or somehow restrict Toth’s ability to challenge the validity of the arbitration agreement before an arbitrator.”

Implications

The 23andme Precedent. The facts in this case bear some similarity to 23andme, which also sells physical kits that require a post-purchase online account with a TOS. 23andme successfully defended this practice despite not giving buyers notice of the online account TOS at time of the kit purchase. (See also the Internet-of-things Wyze Data and FitBit cases). Here, the vendor disclosed the post-purchase TOS on the box (like the old-school disclosures on shrinkwrapped boxes), which made it easier for the court to impute that knowledge to buyers at point of purchase.

Two Clicks Cures Many Problems. Notice how the court keeps going back to the fact that the consumer clicked the checkbox as the definitive answer to every objection she raised. Many TOS formation cases involve tendentious pixel policing of the formation page’s UI. Here, the court didn’t think a screenshot was necessary, and it allocated only a few words to the interface beyond the checkbox. In other words, the checkbox functionally resolved many of the standard objections to TOS formation. I teach my students that 1-click clickthroughs still typically work, but 2-click “clickwraps” are gold standard/best practice for contract formation. This case nicely illustrates the power of the second click.

No One Reads TOSes, and No One Cares. This opinion reinforces what I’ve called the “crisis of online contracts.” As the court acknowledges, reasonable consumers won’t read TOSes, yet consumers are bound to them despite making reasonable choices. This creates a legal fiction that’s out of sync with reasonable consumers’ behavior–hence, a crisis.

For more on online contract formations, see my 2022 Internet Law book chapter.

Case Citation: Toth v. Everly Well, Inc., No. 23-1727 (1st Cir. Sept. 25, 2024)