Amending Your TOS? Better Use a Clickthrough Process, Not Email Notice–Alkutkar v. Bumble

Alkutkar used the dating app Bumble. He paid money to get extra visibility for his dating profile and claims he got poor results, so he sued Bumble for false advertising. Bumble successfully redirects the case to arbitration based on its TOS.

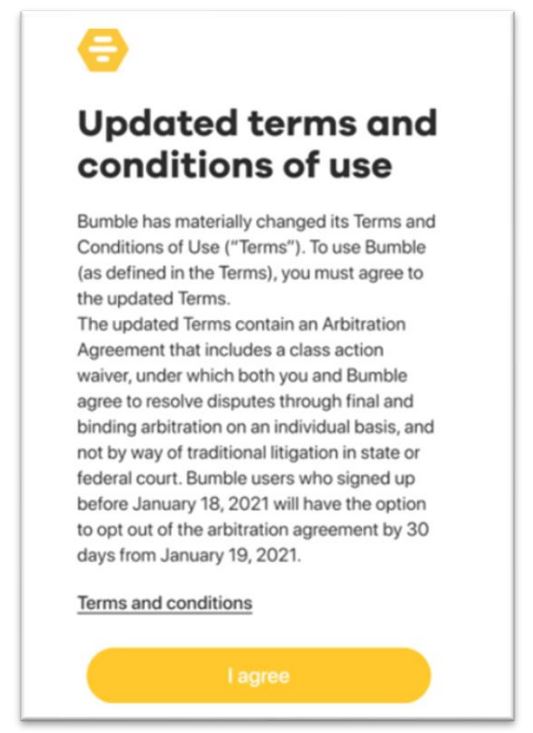

Alkutkar joined Bumble in 2016. In January 2021, Bumble sought to add an arbitration clause to its TOS. It communicated the amendments via an email notice and a “blocker card” that users encountered when they opened up the app:

[The court includes this screenshot, yet the parties apparently agree that the button actually said “I accept” rather than “I agree.” I don’t understand how that happened. Bumble should have been prepared with an authenticatable and dated screenshot of the blocker card. There should never have been any other screenshot to share.]

“Bumble’s records reflect that plaintiff accessed the app for the first time after the Blocker Card was implemented on March 4, 2021, and they infer based on this access that he clicked his assent to the updated Terms.” Users could opt-out of the new arbitration clause by emailing Bumble. Alkutkar didn’t send an email to opt-out of arbitration.

Formation

The court has little regard for the email notice, in part because it apparently didn’t have a call-to-action (if X, then Y). That’s just bad drafting and easily fixed. But properly drafting the email wouldn’t be enough. The court also says “Bumble does not maintain records of the actual emails sent to users, and it has no record that the email was received or even opened.” As to the first part, what? How could Bumble expect to convince a court to find an amendment when it doesn’t have the actual emails??? As for the second part, this appears to be an emerging new requirement (see the uncited Sifuentes v. Dropbox ruling) that services must show that users received and opened emails before they work as amendments. (The court never explains if Bumble’s underlying TOS said amendments could take place by email). Like the Sifuentes case, the court doesn’t treat the email opening requirement as an earthshaking change, but this should be making you increasingly nervous that email-based amendment processes are doomed.

The blocker card analysis goes much better. The court says it’s not a “clickwrap” because it only required one click, not two (ugh). Nevertheless, “the Blocker Card represents a type of clickwrap agreement that should be enforced if accepted by plaintiff because clicking ‘I accept’ to proceed past the Blocker Card required affirmative action demonstrating assent.”

Alkutkar challenged whether he signed the blocker card. A click will suffice per UETA/E-Sign (also not cited by the court). However, Bumble could only infer that he clicked on the blocker card, and Alkutkar claimed he never saw it. The court says that inference is good enough because “defendants offer declarations and documents that they say provide an electronic record of plaintiff’s click of the Blocker Card.” Specifically, Bumble showed:

- “plaintiff’s unique credentials, the same as those internally assigned when plaintiff first registered for a Bumble account, were used to identify plaintiff when he accessed the app on March 4, 2021.” Alkutkar claimed other people had access to his phone (really??), but “plaintiff’s admittedly lackadaisical treatment of his phone, allowing others to access his phone without oversight and leaving apps logged in, does not preclude authentication.”

- “plaintiff’s access and use of the app is a demonstrable consequence of his assent to the updated Terms.” The engineers showed that assent was required to continue using the app. Thus, “plaintiff’s activity on the app on March 4, 2021, including adding photos and swiping on profiles, would not have been possible unless he first clicked to accept the updated Terms.”

Unconscionability

Regarding procedural unconscionability, “the Ninth Circuit has found that a delegation provision is not adhesive and thus not unconscionable if there is an opportunity to opt out of the arbitration agreement.”

The court says there isn’t substantive unconscionability when “(1) Bumble will reimburse all fees and expenses of arbitration for plaintiff’s claims totaling less than $10,000 (unless arbitrator determines claims are frivolous); (2) plaintiff may choose to have arbitration conducted by telephone, based on written submissions, or in person in the country where he resides; and (3) plaintiff has the ability to obtain any monetary or non-monetary relief on an individual basis that would be available in court.”

Implications

Bumble made a series of miscues, including several problems with the email notice and the lack of a definitive screenshot of its blocker card. In light of that, Bumble snatched victory from the jaws of defeat here. What went right?

First, Bumble used a mandatory clickthrough process for the amendment. Most services don’t do this, relying instead on email notice.

Second, the text of the blocker card included both a call-to-action (could have been better, but OK) and reference to the arbitration clause.

Third, Bumble provided users a way to opt-out to the arbitration clause. This is a cheap and effective way of boosting the enforceability of the entire scheme. This also helped alleviate the stress that might have come from any accumulated assets that users had already paid for but would be lost if the user terminated the account. However, make sure the opt-out window starts for each user from the date they see the TOS, not from the date the TOS was posted.

Fourth, Bumble required users to click through the blocker card while logged in (thus being able to show the user’s login credentials were present). Plus, the engineers could support the argument that users couldn’t proceed unless they clicked through.

Fifth, the substantive terms of the arbitration were not oppressive to consumers (even if arbitration is still a losing game for consumers).

Combining this ruling with the Sifuentes ruling, I’m now reluctantly declaring that mandatory clickthroughs for amendments are the new best practice, and email notices–even if worded optimally–are not best practice. Your marketing and engineering teams are going to resent doing mandatory clickthroughs of amendments, so I imagine many of you will keep relying on email notice of amendments because they are so much simpler. But at this point, the odds that you can get a judge to enforce emailed amendment terms keep going down, and the problems of a failed amendment can be dramatic. I’m sorry to be the bearer of bad news, but better to hear it from me than hear it from a judge when it counts.

Also, my repeated reminder that you will need to show the judge how the amendment process worked, including authenticatable and dated screenshots (and video, if there’s any animation) across multiple platforms. And that evidence-preservation must be done in a way that it can convince a judge even if all of the relevant employees have turned over by the time of litigation.

Case citation: Alkutkar v. Bumble, Inc., 2022 WL 4112360 (N.D. Cal. Sept. 8, 2022)

UPDATE: In October 2025, the Ninth Circuit affirmed the arbitration order.