Pre-Publication Content Moderation Can Disqualify Services from the DMCA 512(c) Safe Harbor–McGucken v. ShutterStock

The Second Circuit’s 512 jurisprudence is an unpredictable roller coaster. I can think of at least two other times when the Second Circuit has reversed a clean lower court ruling to unleash further plaintiff-favorable doctrinal chaos (the Viacom v. YouTube and EMI v. MP3Tunes rulings). This ruling adds to that canon, signalling that the Second Circuit has chosen more 512 drama.

* * *

I previously summarized the case:

McGucken is a professional photographer who has appeared on the blog before. He claims that third party “contributors” uploaded his copyrighted photos to ShutterStock as part of ShutterStock’s licensing program. Specifically, McGucken claims that a total of 337 images were uploaded, of which 165 were downloaded and that led to 938 licenses. In total, those licenses generated $2,131 in revenues, split between the contributor and ShutterStock.

The court summarizes ShutterStock’s prescreening efforts:

Shutterstock reviews every image before it appears in the online marketplace. It claims that it does this to weed out images that contain “hallmarks of spamming,” “visible watermarks,” technical quality issues, or material like “pornography, hateful imagery, trademarks, copyrighted materials, [or] people’s names and likenesses without a model release.” Technical quality issues that, according to Shutterstock, could prevent an image from appearing on the platform include poor focus, composition, lighting, and blurriness. Shutterstock’s reviewers examine each image for an average of 10 to 20 seconds and typically each image is reviewed by only one person. Prior to review, Shutterstock automatically removes all metadata associated with the file and allows users to supply their preferred display name and metadata. Shutterstock’s reviewers examine that new user-created metadata, which includes an image title, keywords, and a description.

The district court ruled on summary judgment for ShutterStock on all 512(c) elements. The Second Circuit reverses that conclusion on two elements, likely positioning those issues for trial.

Service Provider. The “broad definition…covers any online platform designed to assist users in doing something that benefits those users.”

Repeat Infringer Policy.

all McGucken has shown is that Shutterstock failed to terminate one repeat infringer. Considering that Shutterstock hosts hundreds of millions of images and videos, uploaded by millions of contributors, the failure to terminate one repeat infringer, standing alone, cannot establish unreasonable implementation. To hold otherwise would require a standard of perfection not contemplated by the statute.

Standard Technical Measures. Metadata doesn’t meet the statutory definition of STMs (nothing does).

Actual/Red Flags Knowledge. “McGucken cites nothing in the record suggesting that any Shutterstock employee ever reviewed the metadata (or lack thereof) associated with his images that were uploaded to the platform.”

Actual/Red Flags Knowledge. “McGucken cites nothing in the record suggesting that any Shutterstock employee ever reviewed the metadata (or lack thereof) associated with his images that were uploaded to the platform.”

Expeditious Removal. “Shutterstock’s removal of the noticed images within four days of McGucken’s DMCA compliant takedown notice was sufficient.”

Storage at User’s Direction. So far, the Second Circuit’s opinion is going smoothly. Now, it takes a dramatic turn for the worse.

The Second Circuit questions if ShutterStock stores its users’ uploads at their direction because it manually prescreens uploads applying its editorial standards:

The task for courts applying § 512(c)(1) is to decide whether a given service provider plays a sufficiently active role in the process by which material appears on its platform such that, as a result, its storage and display of infringing material is no longer meaningfully at the user’s direction….

functions like transcoding, copying, and playback of user-uploaded materials have fallen within the ambit of the safe harbor…

Our caselaw also makes clear that under § 512(c), service providers can review and screen user content before they store it on their platform without becoming ineligible for safe harbor, particularly where the ability to exert control over the content that appears on the platform is necessarily limited by the sheer volume of uploaded user content. [cite to Capitol Record v. Vimeo]…

A service provider may engage in rote and mechanical content screening, like excluding unlawful material, enforcing terms of service, or limiting uploads “to selected categories of consumer preferences,” without falling outside the ambit of § 512(c)(1). On the other hand, a service provider is likely to run afoul of § 512(c)(1) if it is applying its aesthetic, editorial, or marketing judgment to determine which user uploads it accepts….

we adopt the following general rule: if a service provider engages in manual, substantive, and discretionary review of user content—if, on a case-by-case basis, it imposes its own aesthetic, editorial, or marketing judgment on the content that appears on its platform—then its storage of infringing material is no longer “at the direction of a user.” In other words, “extensive, manual, and substantive” front-end screening of user content is not “accessibility-enhancing” and is not protected by the § 512(c) safe harbor.

Boom. Yet another notorious Second Circuit line-drawing exercise that ratchets up defense costs and undermines predictability for both sides.

So what evidence will show that a service is making “aesthetic, editorial, or marketing judgments”? You know this is going to be maddeningly talismanic…and trigger expensive discovery…

the duration of review—that is, how long each piece of user content is under review before it is approved or rejected—and the proportion of user uploads that the service provider accepts are relevant factors to resolving the inquiry. Likewise, the fact that a service provider conducts human review rather than screening images with software may indicate that its content review is more substantive than cursory. But none of these factors is dispositive, and they cannot substitute for the ultimate factual inquiry into the nature of the service provider’s screening of user uploads.

Seriously? Restated: using humans to prescreen increases the service’s legal risk, but only if the humans take too long to review each image (and how long is too long???). FFS.

The court continues reciting the evidence that indicates if the service is making aesthetic, editorial, or marketing judgments:

There is evidence in the record that suggests Shutterstock’s review of user images is neither cursory nor automatic. To begin, when a user submits an image to Shutterstock, the image does not immediately appear on the website; rather, the contributor must wait, sometimes for hours, until they receive an email from Shutterstock letting them know which of their images were accepted. That fact is not dispositive, but it suggests some intervention by Shutterstock between a user upload and the appearance of material on the platform. Moreover, Shutterstock’s website states that it “has high standards and only accepts a portion of the images submitted to be included in [its] collection.”…There are “30-odd” reasons that an image might be rejected by a Shutterstock reviewer, which include focus, exposure, lighting, and noise.

The record also contains evidence that Shutterstock’s reviewers exercise some subjective discretion even when applying seemingly rote and straightforward criteria. For instance, when considering an image’s focus, Shutterstock reviewers are “trained to know the difference between something that’s just out of focus and something that’s more intentional.” And according to Shutterstock, a reviewer may still accept an image that has focus issues if it is “a really unique shot” or a “hard shot to get.”…In the end, as Shutterstock itself concedes, “photography is an art . . . you can’t just say, ‘This is yes, this is no.’” Together, these statements could lead a factfinder to conclude that Shutterstock’s reviewers exercise a considerable degree of case-by-case aesthetic or editorial judgment when determining which images to allow on the platform.

What does the court expect ShutterStock to do here? If it doesn’t screen for image quality, its database becomes cluttered with junk–exactly what successful uploaders don’t want. Maintaining the database’s integrity keeps the credible uploaders from competing with AI slop, and a higher quality database is more likely to draw potential licensees because they can rely on the quality standards so they don’t waste their time. Perhaps the court thinks that running a paywalled licensing database is fundamentally inconsistent with 512(c).

And the idea that a few hours delay for prescreening may be disqualifying? Plaintiffs know what to do with musings like that.

The court continues:

Shutterstock counters that its front-end screening is rote and mechanical—that its reviewers consider only “apparent technical issues or policy violations.” And indeed, there is evidence in the record that supports that characterization. For one, as Shutterstock emphasizes, a reviewer typically spends no more than 10 to 20 seconds examining an image. Further, there is evidence in the record that approximately 93 percent of submitted images are approved for the platform. A factfinder might conclude that such a high “success” rate supports an inference that it is the users, and not Shutterstock’s reviewers, who dictate the images that appear on the site….

Of course, approving a high rate of submitted images could indicate that Shutterstock’s image screening is limited and permissive. Alternatively, a high image acceptance rate could suggest that Shutterstock’s contributors know what types of images are likely to be approved and proactively curate their own submissions. Indeed, the record suggests that one reason Shutterstock gives its contributors guidance on the images to submit is to reduce the likelihood that an image will be rejected. Similarly, a platform that successfully coaches its contributors on the types of images it prefers to display may generally have to spend less time reviewing each individual image. Therefore, while a low acceptance rate may indicate that a platform is selective in the content it accepts, a relatively high acceptance rate does not invariably establish the opposite.

As the old adage goes, if you’re explaining, you’re losing. Any service that has to haggle with plaintiffs over whether their content moderation is sufficiently “rote and mechanical”–e.g., whether their reviewers are lingering too long over a particular upload or rejecting too many uploads–has already lost the game.

Also…what’s the difference between (1) articulating content editorial standards in your TOS (which many regulators are now demanding, though those edicts may be unconstitutional), and (2) “coaching” users about what uploads are proper?

Right and Ability to Control the Infringements.

[Reminder: courts have redefined this factor to turn on whether the service exercises “substantial influence” over users’ activities. That redefinition clarified nothing, so we’re back to epistimological inquiries.]

Citing Vimeo, the court says “a service provider does not necessarily exercise substantial influence over user activities merely because it screens every upload before it appears on its platform.” In Vimeo, the court said a video-sharing platform could permissibly impose content gatekeeping criteria that “were in the nature of (i) avoiding illegality and the risk of offending viewers and (ii) designing a website that would be appealing to users with particular interests.” In Viacom, the court said substantial influence exists “where the service provider instituted a monitoring program by which user websites received ‘detailed instructions regard[ing] issues of layout, appearance, and content.’”

Here, the court says: “the relevant inquiry here is whether the image pipeline Shutterstock has constructed—which begins with its lengthy guidelines for successful submissions and ends with manual image review—enables Shutterstock to exercise substantial control over the images that appear on its platform.”

An “image pipeline”? Are we reinvigorating 1990s metaphors about surfing the Internet? 🏄♀️

The court identifies the relevant evidence to this standard:

Shutterstock screens every image before it appears on the platform—this screening determines whether an image ever gets on the platform….there is evidence here that Shutterstock’s image review goes beyond the limited purposes of restricting the site to “selected categories of consumer preferences” and excluding unlawful images. Rather than engaging in categorical content screening—like accepting only holiday-themed images, or images that feature animals—Shutterstock appears to screen user images for their overall aesthetic quality. Curating a “collection” of high-quality images is not the same as designing a website “that would be appealing to users with particular interests.”…

Shutterstock extensively advises potential contributors on the types of images it is likely to accept. That is unlike the service provider in Vimeo II, which “encouraged users to create certain types of content,” but did not condition their ability to post material on whether they created the provider’s preferred types of content….a reasonable factfinder might conclude that the advice and instruction Shutterstock provides its contributors, coupled with its image screening process, are sufficiently coercive to constitute substantial influence….

the duration of Shutterstock’s image review and its 93 percent approval rate are relevant facts, but they are not dispositive

One way of reading this is that the Second Circuit is collapsing the distinctions between the “stored at a user’s direction” and “right and ability to supervise” factors, because apparently they both depend on the same evidence?

1202 CMI

ShutterStock automatically strips out the metadata of uploaded images and adds its own watermark to every image in its database. The court says the 1202 claims fail:

McGucken points to no evidence suggesting that Shutterstock affixed its watermark to his images—or, indeed, to any images—with knowledge that it constituted false CMI and for the purpose of concealing copyright infringement…

While Shutterstock concededly knows that it removes CMI from every image ingested into its system, Shutterstock explained—and McGucken failed to refute—that it removes metadata from all images primarily to avoid computer viruses and the dissemination of personally identifiable information, and not for any reasons related to infringement.

This ruling reinforces that 1202 has a “double scienter” requirement, which should help curb other 1202 cases–especially the cases against generative AI model-makers.

Implications

Second Circuit Walks Back the Vimeo Case. Last year’s Vimeo opinion was written as if it was a watershed Section 512(c) defense win, but it didn’t draw much attention. Why? First, I viewed it as a Pyrrhic defense victory because it added yet more details that plaintiffs could attack to disqualify 512(c) defenses. Second, I think no one really believed other Second Circuit panels would defend the 512(c) safe harbor the way Judge Leval tried to do. And here we are. A year after the Vimeo opinion, and the next Second Circuit panel to address Section 512(c) compounds Section 512(c)’s complexity and undermines 512(c) for any service that prescreens content.

(Note: the Second Circuit did the same thing a decade ago. The EMI v. MP3Tunes decision walked back a defense-favorable Vimeo ruling that had come out not that long beforehand).

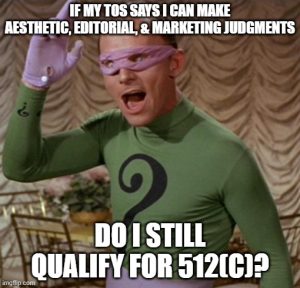

The Incoherent Standard for User-Directed Storage. The Second Circuit says: “A service provider may engage in rote and mechanical content screening, like…enforcing terms of service” and still qualify for 512(c). However, the service loses 512(c) if it “imposes its own aesthetic, editorial, or marketing judgment on the content.”

The Incoherent Standard for User-Directed Storage. The Second Circuit says: “A service provider may engage in rote and mechanical content screening, like…enforcing terms of service” and still qualify for 512(c). However, the service loses 512(c) if it “imposes its own aesthetic, editorial, or marketing judgment on the content.”

Hello…does anyone else see the intractable conflict? A service can always claim it is “enforcing its terms of service” when moderating content, so this legal standard sets up an obviously false dichotomy. The opinion then suggests there are right and wrong kinds of TOS terms, such as its discussion about impermissible “coaching” to secure the right kinds of uploads. At minimum, this ensures more expensive discovery and fights over how the Second Circuit purported to thread this needle.

Bonus conceptual dilemma: the court says 512(c) disqualification occurs if a service “imposes its own aesthetic, editorial, or marketing judgment on the content that appears on its platform,” and then it says that the evidence for this is if the service does “manual, substantive, and discretionary review of user content.” These are not the same thing! Content moderation always involves difficult judgment calls and line-drawing exercises, so it’s possible to do “manual, substantive, and discretionary review of user content” for reasons other than imposing “its own aesthetic, editorial, or marketing judgment on the content that appears on its platform.”

Then again, the inclusion of the word “editorial” makes the court’s standard a non-standard. Every content moderation judgment is an editorial decision of some sort. Thus, the phrase “rote and mechanical content screening” is incoherent.

This Opinion is an Attack on Content Moderation. Restated, this court says that some pre-posting content moderation disqualifies defendants from 512(c). But which content moderation techniques should defendants avoid if they care about 512(c)? No idea. The court puts every content moderation decision in play. Reviewers took too long. Reviewers tried to screen out junk submissions. Reviewers made judgment calls about how to apply standards (which every content moderator must do with every decision). The services’ rejection rates are too high. The service did too much “coaching” of what uploads it wanted. In other words, there is no safe harbor for content moderation that ensures the safe harbor for user-caused copyright infringement. Plaintiffs can attack everything.

The court’s “guidance” to services is to do less content moderation if they want toincrease their eligibility for 512(c). This is a terrible message to send, especially now. As a reminder, Section 230 was written because Congress wanted to encourage, not discourage, content moderation. Further, it’s tone-deaf about what’s going on in the real world right now. We desperately NEED more content moderation, not less; we need more efforts to identify or screen out AI slop; we need more efforts by services to encourage civility and discourage rage. The Second Circuit, instead, wants to trigger liability if content reviewers maybe think a few extra seconds about whether something should go live or not. The Second Circuit really needs to read the room.

I will also add that this opinion implicitly encourages services to impose stricter time limits on content reviewers’ average review times, even though such time limits will likely increase the overall stress and burnout of content reviewers. This is a decidedly human-unfriendly opinion at every level. Or maybe the Second Circuit thinks services should shift more content review to the algorithms???

Case citation: McGucken v. Shutterstock, Inc., 2026 WL 364412 (2d Cir. Feb. 10, 2026)

This ruling might inspire you to revisit my essay, How the DMCA’s Online Copyright Safe Harbor Failed.