Fair Use Blocks Privacy-Motivated Copyright Lawsuit–MCM v. Perry

The case involves a Twitter user, Perry (a/k/a “I, Hypocrite”), who tweet-critiqued a crypto company Celsius Networks. The first tweet in the sequence referenced a business setback for Celsius. The second tweet in the sequence contained a collage of two images with the caption “Same company btw” (i.e., Celsius).

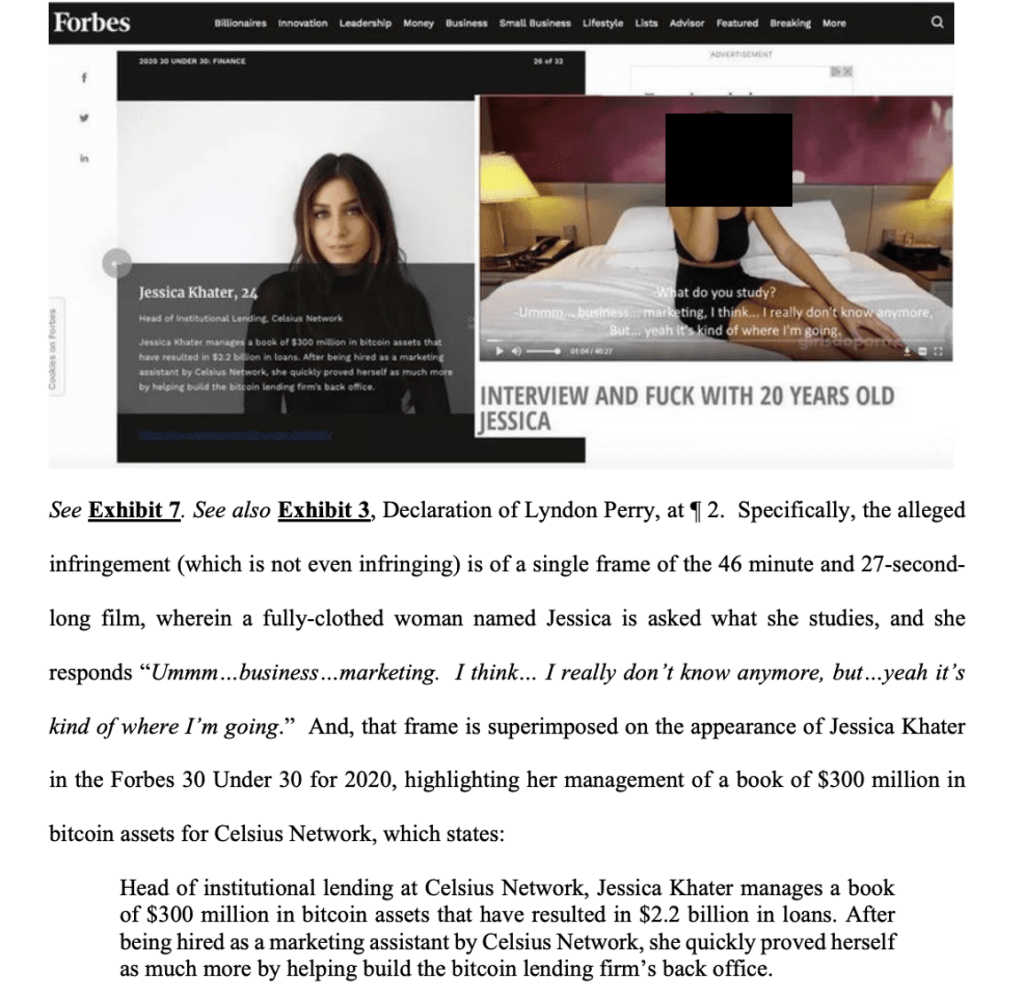

The first collaged image shows Jessica Khater’s, a Celsius executive, listing in Forbes 30 Under 30. The second collaged image is a screenshot from an unnamed video that depicted “Jessica” with the transcription that she studied marketing and business. The juxtaposition implied that Jessica and the Forbes 30 Under 30 executive were the same person.

The court is as baffled by this tweet thread as you are (“This Court makes no finding as to what Defendant subjectively intended to communicate through the Tweet, as the Defendant’s intentions are not alleged within the complaint or obvious from the Tweet itself”). Connecting the dots, perhaps the inference is that the Forbes 30 Under 30 executive studied business and marketing, worked for Celsius, and thus might be responsible for Celsius’ downfall. Or perhaps the inference is that the Forbes 30 Under 30 executive chose to make porn earlier in their life (which, as discussed in a moment, would not be true) and that choice relates to their competence or reputation. If either inferential chain seems illogical or shaky, recall this is a social media tweetstorm about crypto, a notoriously chaotic corner of the information ecosystem. The court never expressly resolves if the video Jessica and the Forbes 30 Under 30 executive are the same person.

The screenshot is included in the court filings, and the similarities of the two faces is directly relevant to the tweet sequence’s meaning. Nevertheless, I’m covering up “Jessica’s” face because she is a sex trafficking victim:

The screenshot was extracted from an unnamed sexually explicit video produced by Girls Do Porn (GDP). As you can see, the screenshot isn’t sexually explicit (Jessica is depicted on a bed fully clothed). In prior proceedings, another court held that GDP was “a criminal sex trafficking enterprise” and awarded restitution by transferring the IP rights in the videos to the victims–presumably to give the victims additional legal tools to suppress further disseminations of the video. (I didn’t work through the 17 USC 201(e) implications of the prior restitution order).

“Jessica” received the copyright to the video from which the screenshot was extracted and assigned the rights to an enforcement agent. Jessica’s enforcement agent sent a 512 takedown notice to Twitter targeting the screenshot. Twitter removed the tweet.

Despite the removal, Jessica’s enforcement agent also sued Perry for copyright infringement for posting the screenshot in the first place. The court dismisses the claim due to fair use–on a motion to dismiss.

Nature of the Use

the Tweet utilized the still frame for a transformative purpose. The Video is a pornographic film with the express purpose of displaying explicit sexual content. Conversely, the Tweet does not contain any nudity or sexually explicit imagery and is framed as a commentary on Celsius….

The Defendant’s reproduction of the still frame in the composite image is in service of this commentary….By arranging the images of two women, both identified as being named Jessica, side by side, the composite image vaguely implies that a Celsius executive appeared in a pornographic film. The still frame’s accompanying text stating that Jane Doe was studying business and marketing further supports this implication.

In short, a reasonable observer would understand the Tweet as a commentary on Celsius with a markedly different purpose from the original pornographic video. Further, as a commentary on a “subject of public interest” (i.e., Celsius’ decision to pause its customer’s transfers and withdrawals), the Tweet’s transformative use of the still frame justifies its copying.

Nature of the Work. The court says this factor is neutral and not important.

Amount Taken

the Tweet reproduced a single frame of a forty-six-minute video….The Tweet does not capture the central expression of the Video and is not a substitute for the original. The heart, or core, of the Video is its sexually explicit imagery. The Tweet is not pornographically explicit and shows a fully clothed woman describing her career interests.

Market Effect

Defendant’s use of a single still frame from the Video was a transformative secondary use intended as a form of commentary on Celsius. Further, the Defendant’s use of a single frame from the video did not include any sexually explicit imagery. In short, a person in the market for a sexually explicit, pornographic film would not turn to the Tweet. Because Defendant’s use of the still frame would not, and could not, usurp the market for the Video…

Plaintiff admits that the Tweet would not harm the market for the Video.

Implications

Do Screenshots Extracted from Videos Infringe? In general, I think that single images extracted from videos should routinely qualify as fair use. This case involved more complicated facts, because the video’s screenshot compared the depicted individual to the Forbes 30 Under 30 segment in service of a larger critique of Celsius. Many extracted screenshots from videos won’t similarly engage in social commentary or need to present the screenshot as visual evidence to support the commentary.

Even so, if the extracted screenshot merely illustrate the video or the person depicted, or provides the foundation for a meme, the republication of a screenshot is a trivial fraction of the source work and poses no threat to the market for the originating video. In other words, the last two fair use factors should always weigh in the defendant’s favor. This case may not be definitive precedent to establish that other screenshot publications should routinely qualify as fair use, but it shows a roadmap to that conclusion.

Copyright and Overremovals. Twitter honored to Jessica’s enforcement agent’s 512 takedown notice by removing the tweet. However, this court opinion confirms that the tweet was never infringing. As a result, Twitter’s response appears to be yet another unwarranted 512-induced overremoval (I have another post about DMCA overremovals coming soon).

When Takedowns Don’t Satisfy the Copyright Owner. We don’t often see copyright owners sue uploaders after a successful 512 takedown. 512 doesn’t eliminate those lawsuits; instead, 512(h) facilitates such lawsuits by helping copyright owners unmask the uploader. Nevertheless, the incremental value of a copyright infringement lawsuit after a successful takedown is typically small. The need for an injunction has essentially evaporated; lawsuits take a long time chronologically and cost more money; the damages at issue might be trivial (especially if the takedown was effectuated quickly); and the copyright owner runs the risk of a Streisand Effect (an especially acute risk here given the privacy motivation of this lawsuit). I’m not sure what the plaintiff hoped to accomplish with this post-takedown lawsuit.

Copyright as a Silencing Mechanism. This lawsuit seemed to be motivated more by privacy concerns than copyright. The plaintiff admitted as much: “Plaintiff wishes to depress the demand for the Video and use the Federal Copyright Law to control further dissemination of the Video, or any portion thereof” (cleaned up).

While copyright law can act as a doctrinal tool for suppressing content, it’s ill-suited as a privacy tool for reasons that Prof. Silbey and I discussed in our Copyright’s Memory Hole paper. As we wrote there, “treating copyright law as a general-purpose privacy and reputation tort harms us all.”

I’ll note that the complaint only alleged copyright infringement–no defamation, false light, or privacy claims. I wonder if any of those alternative claims would have been more appropriate to address the underlying privacy concerns?

* * *

I feel sympathy for Jessica’s sex trafficking victimization. However, especially after Twitter’s takedown of the screenshot, this copyright lawsuit was also problematic. I still believe that any time a court grants fair use on a motion to dismiss, a 505 fee shift to the defense should usually follow because the legal claims weren’t close.

Case Citation: MCM Group 22 v. Perry, 2026 WL 279525 (S.D.N.Y. Feb. 3, 2026). The complaint. Defense counsel’s writeup of the case.