Using a Meme in Your Advertising? Clear the Publicity Rights–FJerry v. Oasis Energy

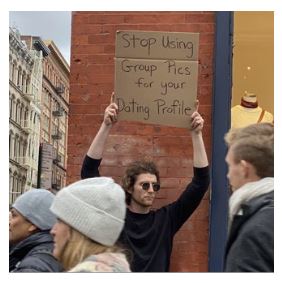

This case involves a photo from the “Dude With Sign” meme series, featuring Seth Phillips in the titular role:

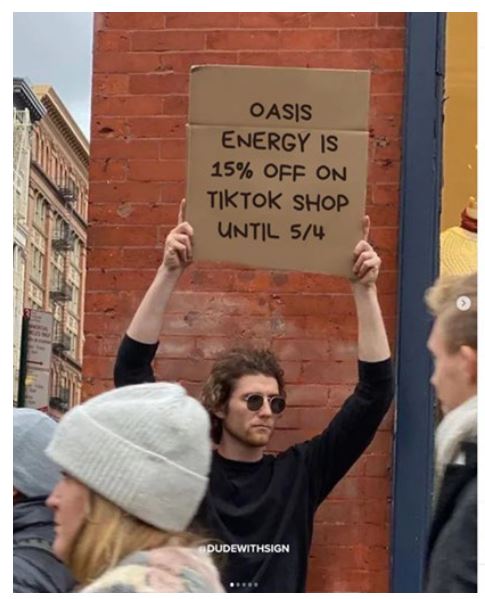

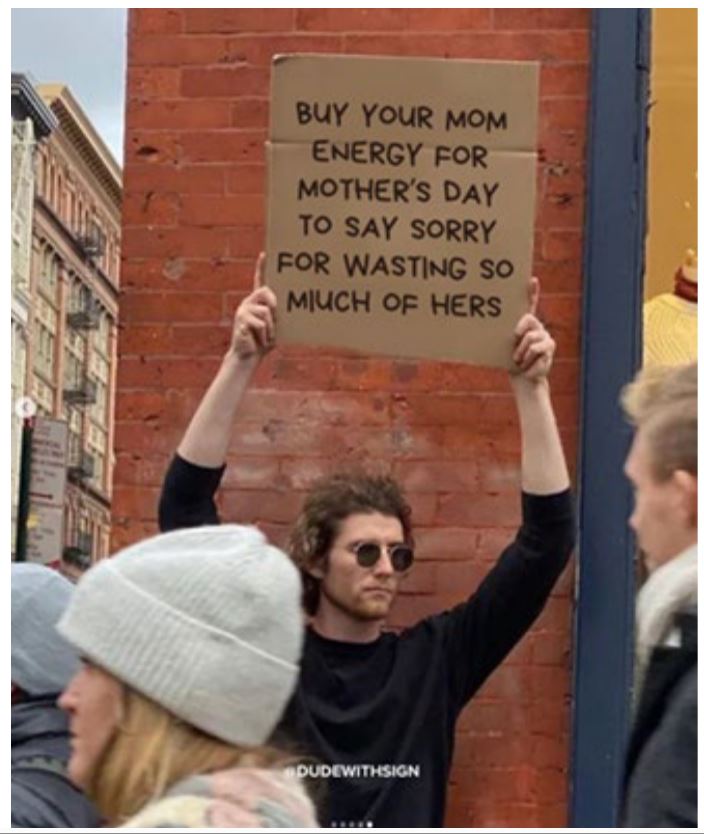

An advertiser, Oasis Energy, modified the meme to promote its offerings in two social media posts:

FJerry owns both the copyright to the meme and Phillips’ publicity rights.

Copyright

Oasis tried some weak arguments to dismiss the copyright claim:

Oasis modified the image. The court responds:

The modifications are not so vastly different that the allegedly infringing images bear no passing resemblance to the original. The individual in the allegedly infringing photos is the same as the one in the copyrighted photo. Further, the “format” of the allegedly infringing photos — of Phillips holding a sign bearing some text — is the same. The main differences are the specific words written on the allegedly infringing photos and the process through which the words were written, i.e., through an image-editing software, rather than handwritten on cardboard. But that distinction alone does not mean that no reasonable jury could conclude that Oasis infringed upon FJerry’s copyright.

Oasis made a de minimis use. This is an odd argument, and the court recharacterizes it as a fair use defense, and “Courts generally cannot consider fair use when resolving a motion to dismiss.” To be clear, Liebowitz produced a string of defense fair use wins on motions to dismiss when he brought terrible lawsuits–but I don’t think the fair use argument is as obvious here.

Also, the court rejects the idea that “the use was “fleeting” simply because the defendant removed the post upon notice,” especially when the ad was online for a month.

Oasis claimed “no monetary or commercial value was gained from use of the allegedly infringing work.” I’m not sure what this means, but this seems dubious. If the advertiser makes two social media advertising posts and make no sales from the ads, then they have major problems with their business. Plus, the plaintiff is unhappy about any lost licensing revenues.

Meme usage is protected by the First Amendment. Citing Rogers v. Grimaldi,

Oasis contends that the images here are referential and expressive because they were a visual allusion to a widely known meme. Oasis further presses that the meme has become shorthand for “ironic or humorous observations,” its use by Oasis was consistent with that purpose, and there was no false claim of sponsorship, no deceptive message, and no attempt to exploit the identity or goodwill of the individual in the meme for commercial gain.

The cite to Rogers v. Grimaldi confuses the court (and me), because that case only applies to trademarks, not copyrights. Plus, the content items at issue are ads, not the kind of expressive content at issue in the Rogers case.

Publicity Rights

the Complaint pleads the proper elements of a claim for right of publicity. Oasis contends that the Complaint fails to allege that Oasis used Phillips’ likeness for commercial or nonfleeting purposes, necessary elements of a right of publicity claim. But that is plainly incorrect.

Your evergreen reminder that even if you’ve secured all of the requisite copyright licenses for your ads, you still need the publicity rights consent. Meme status doesn’t change this at all. I flagged the same issue in connection with the Griner v. King meme copyright decision.

One obvious countermove: Oasis could have pretty recreated an inspired-by photo using models who signed proper publicity rights consents. Instead, it chose the incredibly lazy and legally unwise path.

False Endorsement

I’m not sure what trademark protection applies to the meme, but Oasis instead focused on the consumer confusion prong for the motion to dismiss. The court is unpersuaded:

Though the advertisements did not include Mr. Phillips’ name, a consumer could still be confused about Mr. Phillips’ relationship to Oasis’s product, given that Mr. Phillips’ image and likeness is in the allegedly infringing photos, in his “classic” pose — holding up a sign with text on it.

The photo’s meme status doesn’t change the analysis (at least, not yet):

Though Oasis maintains that the ManWithSign format functions as a visual shorthand for social commentary, rather than endorsement, that inquiry is inappropriate at this stage in the proceedings. Deciding whether the meme has become a “widely used satirical device,” rather than a vehicle for endorsements, would take the Court down a highly fact-dependent inquiry that would be best resolved at a later stage of litigation.

The Rogers v. Grimaldi invocation is more logical here than in the copyright discussion, but the court quickly rejects it because the items in questions are ads, not expressive works.

In a last-ditch effort, Oasis tries to throw the meme generator under the bus, to no avail:

Oasis also presses that the existence of an online meme generator, ImgFlip, that permits users to create memes using the ManWithSign format defeats FJerry’s claims. Not so. ImgFlip has an extensive list of terms of service on their website that limit how users may use content from the website. Among other things, those terms indicate that users “may not use content from our Services unless you obtain permission from its owners,” that ImgFlip does not give users “ownership of any intellectual property rights in our Services or the content you access,” and that users agree to “indemnify and hold ImgFlip harmless from and against any and all claims . . . that arises out of or relates to your infringement of any third party’s rights.” Further, the fact that ImgFlip allows users to edit copyrighted images on their website means only that a copyright holder could bring suit against both ImgFlip and the user. ImgFlip’s services, in other words, do not bear upon this action.

I imagine ImgFlip is muttering “thanks for nothing” to Oasis for sideswiping them. 🙄 I’ve lost track of the times I’ve tested on the legal liability of meme generators; my 2007 Internet Law exam (1, 2) is the first that came to mind.

Case Citation: FJerry LLC v. Oasis Energy Drink LLC, 1:25-cv-06088-JSR (S.D.N.Y. Oct. 30, 2025)