The Wrap Taxonomy Vexes the Judge in the LinkedIn Insight Tag Cases

In the LinkedIn “Insight Tag” cases, Judge Davila issued two opinions where he classified UIs into the Wrap Taxonomy–and left a trail of appeallable issues in his wake.

L.W.A. v. LinkedIn Corp., 2025 WL 2780788 (N.D. Cal. Sept. 30, 2025)

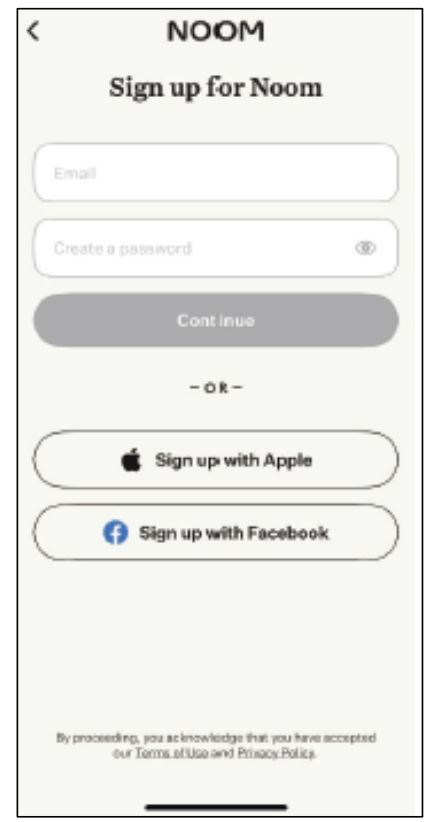

The plaintiff claims to have completed an online weight loss plan, including the disclosure of sensitive information, using the “Noom” app. Noom’s TOS includes an arbitration clause. The plaintiff sued LinkedIn but not Noom. LinkedIn invoked Noom’s arbitration agreement.

This requires the court to evaluate Noom’s TOS formation:

This is a standard sign-in-wrap, but baffingly, Judge Davila labels this a “modified” sign-in-wrap. WTF? Immediately beforehand, the court references how sign-in-wraps are “modified clickwraps,” which itself is a trash statement because a clickwrap has 2 clicks and a sign-in-wrap has one, so they can’t be equated under any circumstance. So did Judge Davila mean to call this a modified clickwrap but made a typo? Did he actually mean to call it a modified sign-in-wrap, even though that term is meaningless? The avoidable semantic ambiguity made me cry a little. I eagerly await the day the wrap taxonomy is abandoned.

Transaction Context. The opinion says someone developing a weight loss plan should expect an ongoing relationship governed by terms.

Visual Placement.

the Court finds that the visual placement of the Terms of Use hyperlink provides sufficient notice for several reasons. First, the page is free from clutter. There are simple boxes to input an email and password, or sign up through Apple or Facebook accounts, followed by significant white space surrounding the Terms of Use notice. Second, the hyperlinks are not buried in text or otherwise placed in a confusing location—the sentence containing the Terms of Use notice is the only text in the white space at the bottom of the page. Third, though the font is grey, it appears clearly in contrast against the white background. Finally, while the hyperlinks are not marked in blue, they are in bold and underlined, making them stand apart from the other text in the sentence. In the context of the clean and simple format of the page, the Court finds that a reasonably prudent internet user would see the notice and understand that the phrase “Terms of Use” was a hyperlink to the terms containing the Arbitration Clause.

This ruling is plainly out-of-sync with Chabolla and Godun. The two obvious showstoppers are (1) the visual break between the “continue” button and the call-to-action, including the buttons to sign up with Apple or Facebook. There is no reason for a user to look below the “continue” button if they are set to go with the credentials. The “-or-” interposition further signals that users should stop reviewing the page if they have already made their choice. (2) the “continue” button does not match the “proceeding” grammar in the call-to-action. This mismatch was fatal in the Godun case. I also think the Chabolla and Godun courts would have a problem with the small grey font on a tan background.

At best, Noom was following old standards for sign-in-wraps, but the Chabolla and Godun cases raised the TOS formation bar so much that this formation process looks completely antiquated now. If the Ninth Circuit meant what it said in Chabolla and Godun, this court’s take on Noom’s visual placement should be an easy reversal if the plaintiff appeals.

Assent to Terms. “when Plaintiff successfully created her account on September 20, 2024, she agreed to Noom’s Terms and Privacy Policy. Plaintiff does not dispute this.”

Equitable Estoppel. To resolve this case, “the court would need to examine whether Plaintiff consented to her data being shared to LinkedIn in her agreement with Noom….Plaintiff’s claims are intimately founded in and intertwined with her agreement with Noom, and LinkedIn may enforce the Arbitration Agreement through the doctrine of equitable estoppel.”

I’m not an expert on this topic, but the court’s logic seemed like a nonsequitur to me. Even if the resolution of the plaintiff’s claim requires a resolution of whether Noom’s TOS formed and adequately disclosed LinkedIn’s behavior, there is no reason why LinkedIn must also piggyback on Noom’s arbitration clause, especially when Noom itself wasn’t sued and won’t be in the arbitration. I could see the Ninth Circuit reversing this ruling too if it’s appealed.

* * *

L.B. v. LinkedIn Corp., 2025 WL 2782588 (N.D. Cal. Sept. 30, 2025)

This is another LinkedIn Insight Tag case. There is a lot going on with this opinion. I’ll address only the cookie banner consent issue.

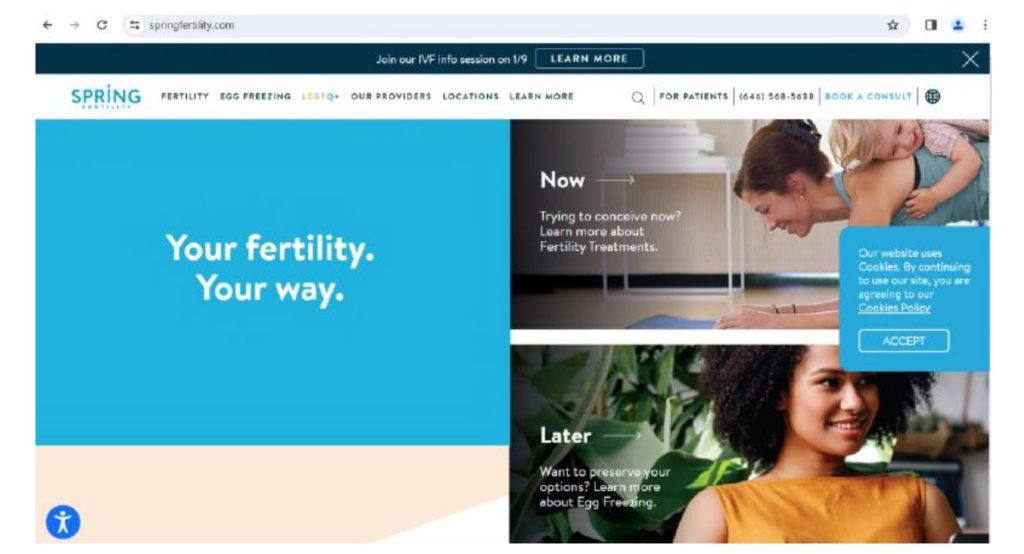

One of the plaintiffs sued LinkedIn and Spring Fertility. Spring Fertility’s website contained a pop-up cookie banner (it’s the blue box on the right):

The question is: did the plaintiff have actual or constructive knowledge of the terms of the cookie policy?

Judge Davila again struggles with the wrap taxonomy:

the notice here falls somewhere in between a browsewrap and a modified clickwrap agreement—though users are not required to click a button to assent to the terms, they are informed that they assent to the terms by continued use of the website, and users may click a button to “ACCEPT” the terms. Cookie banners such as this can still create constructive notice if the terms are reasonably conspicuous.

To be fair, Judge Davila is correct that the cookie banner is not exactly a browsewrap or a sign-in-wrap. It’s a tertium quid with no wrap taxonomy node. When we find interfaces that fall between the wrap taxonomy nodes, it’s a good sign of the taxonomy’s deficiencies. I continue to believe the entire taxonomy should be completely reevaluated. It’s confusing to judges and undermining the predictability of TOS enforceability for online services.

For me, the question is: does any consumer have any reason to click on “accept” button (even if it’s not mandatory)? If not, the placement is pretty easy to ignore and I would say that any consumer that didn’t click on the accept button by definition hasn’t taken any affirmative steps to confirm assent to the cookie policy.

Judge Davila sees it differently:

The visual placement of the Cookie Banner here could provide sufficient notice of the Cookies Policy and Privacy Notice for several reasons. First, the notice is written in clear font in the middle of the page with a contrasting blue box as a background and no surrounding clutter. The also message [sic] clearly informs users in plain language that continued use of the website constitutes acceptance, and though not required, users are notified that they can consent to the policy by clicking a large box with “ACCEPT” written in all caps. Finally, the “Cookies Policy” hyperlink is underlined and capitalizes the first letter of each word. In the context of the clean and simple format of the page, the Court finds that a reasonably prudent internet user would see the notice and understand that the continued use of the website constitutes agreement to the Cookies Policy, and that “Cookies Policy” is a hyperlink that ultimately leads to the terms of the Cookies Policy and Privacy Notice

I have issues with this. First, I disagree that there is no surrounding clutter. The box literally sits on top of two separate photos that introduce substantial visual clutter. Second, if the judge is saying that the call-to-action (“By continuing to use our site, you agree…”) is effective, then the court is accepting browsewrap language even though browsewraps are usually unenforceable. The judge’s further discussion seemingly reinforces that he’s treating browsewraps as enforceable (e.g., the opinion also says that “the Cookie Banner clearly states that users agree to the terms of the Cookie Policy by continuing to use the website. It also prompts users to take another affirmative action to demonstrate consent by clicking “ACCEPT.””). Third, the judge provides no support, other than his intuition, for how a reasonably prudent Internet user would evaluate this user interface, even though there are many empirical studies on this point.

In my view, the plaintiff should be bound by the cookie policy only if (1) the plaintiff actually clicked on the “accept” button, or (2) the applicable privacy claims could be satisfied by consumer disclosures that don’t rise to the level of TOS formation AND the court concludes that the linked information was sufficiently prominent to satisfy that sub-TOS formation standard. Because the judge instead seems to say that the browsewrap disclosure was good enough, I think this specific ruling would be vulnerable on appeal.

#AbandonTheWrapTaxonomy.

BONUS: I searched Westlaw for the term “cookie banner” and came up with 14 judicial opinion hits, including this case. I took a quick spin through the cases and it seemed like the judicial analysis of cookie banner enforceability is underdeveloped. Students, if you’re looking for a paper topic, it might be worth reviewing the interplay between cookie banners and the evolving TOS formation jurisprudence, especially post-Chabolla and Godun.