Analyzing the Lululemon v. Costco Dupe Suit (Guest Blog Post)

Guest blog post by Profs. Sarah Fackrell & Alexandra J. Roberts

Dupe culture is everywhere. Consumers seek out dupes online, in stores, and on social media, hoping to score less expensive versions of the luxury items they lust after; stores and influencers increasingly position products as dupes, a form of comparative advertising they hope will catch the attention of those consumers. But “dupe” is a term that can mean a lot of different things, from legitimate alternatives to straight-up counterfeits. Determining when a dupe seller crosses the line and a dupe infringes intellectual property rights can be tricky.

The legal issues dupes raise aren’t necessarily novel. Certain types of dupes are just an update on the concept of “house brands” or “private label brands,” which are usually deemed unlikely to cause confusion. When a chain retail store places a nationally-known brand—say, Herbal Essences shampoo—next to a generic or store brand version featuring lookalike packaging and a similar but non-identical name like “Organic Essentials,” consumers tend to understand what they are (and are not) getting. [Eric’s note: for a discussion about these physical-space adjacencies, see this paper.]

But the rise in dupes has brought a corresponding rise in dupe lawsuits, or at least lawsuits that offer up defendants’ or consumers’ use of the term “dupe” as evidence of confusing similarity or intent to deceive. The most recent of those is Lululemon’s suit against Costco. Filed June 27 in the Central District of California, the complaint alleges Costco infringes Lululemon’s trademark, trade dress, and design patent rights in its Scuba hoodies and sweatshirts, DEFINE jackets, and ABC pants.

According to Lululemon, with dupes, the confusion is the point: “one of the purposes of selling ‘dupes’ is to confuse consumers at the point-of-sale and/or observers post-sale into believing that the ‘dupes’ are Plaintiffs’ authentic products when they are not.” Despite the reference to post-sale confusion, though, Lululemon’s trademark and trade dress claims focus on confusion at the point of sale. And despite the assertion of “prestige and renown” of the sub-brands and products in play (renowned pants, really?), the company did not include a dilution claim, nor would it likely succeed with one. Lululemon dupes are widely sought-after—the company cites the popular #LululemonDupes hashtag proliferating on TikTok and other social media platforms—and these particular dupes have already garnered a lot of attention, including write-ups in the New York Times and Washington Post that focused on their similarity to the Lululemon pieces. But none of that guarantees a finding of infringement.

Lululemon also points out that private-label products account for over a third of Costco’s sales, but Costco doesn’t inform shoppers which of the products they sell are private-label-licensed and which are not, increasing the likelihood of confusion. In other words, if shoppers (correctly) believe that Kirkland diapers are made by the manufacturers of Huggies and Kirkland batteries come from Duracell, they might also assume that a “Kirkland 5 Pocket Performance Pant” that looks similar to Lululemon’s ABC pant is, in fact, the same pant manufactured by Lululemon under agreement with Costco and sold under a different name and at a different price point. That argument could potentially be compelling, but it’s undermined by the fact that only one of the six products at issue is sold under the Kirkland brand, and several are sold bearing trademarks from well-known clothing brands such as Danskin and Jockey.

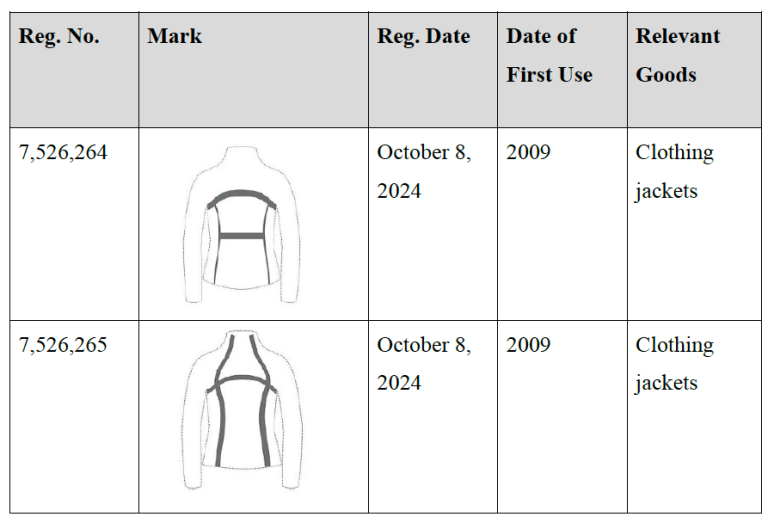

The first product Lululemon discusses in its complaint is the DEFINE jacket, for which the company owns two federal trade dress registrations and, it alleges, common law trade dress rights.

Lulemon articulates the trade dress to comprise “a jacket having:

- approximately mirror image curvilinear ornamental lines on the front of the jacket;

- one set of the mirroring curvilinear ornamental lines on the front extend from the chest to the waist;

- another set of the mirroring curvilinear lines extending from the chest toward the neck region;

- a curved ornamental line that extends across the mid-back region of the jacket; and

- an approximately mirror image curvilinear ornamental line from below the ornamental line across the mid-back of the region towards the bottom seam of the jacket.”

Lululemon goes on to argue that the trade dress has become distinctive and source-indicating, citing examples of third-party media coverage and television appearances and including photos of celebrities wearing the product.

An accused infringer might be contemplating whether the asserted trade dress is functional. That’s probably why Lululemon is already on the defensive, including in its complaint photos of non-infringing jackets from third parties and asserting “The design features embodied by the DEFINE Trade Dress are not essential to the function of the product, do not make the product cheaper or easier to manufacture, and do not affect the quality of the product. The design elements of the DEFINE Trade Dress are not a competitive necessity for apparel products.” It includes a similar rebuttal and images of non-infringing products for each of the allegedly infringed clothing items.

But utilitarian functionality and aesthetic functionality might both be in play, and “not a competitive necessity” doesn’t adequately address the test for the latter. In most jurisdictions, courts ask whether granting one party exclusive rights to a feature puts competitors at a non-reputation-related disadvantage. That test is broad enough to encompass design elements that consumers want because they give the product a desirable look, even if they’re not “necessary.” In the case of the DEFINE jacket, the curvilinear lines might make the jacket more flattering by creating the impression of curves underneath, or they might just look cool. A jacket that lacks curvilinear lines or features them with different placement might be less appealing not because it lacks features that serve as source indicators, but because it lacks features consumers want—putting competitors who can’t use those features at a disadvantage that isn’t about brand.

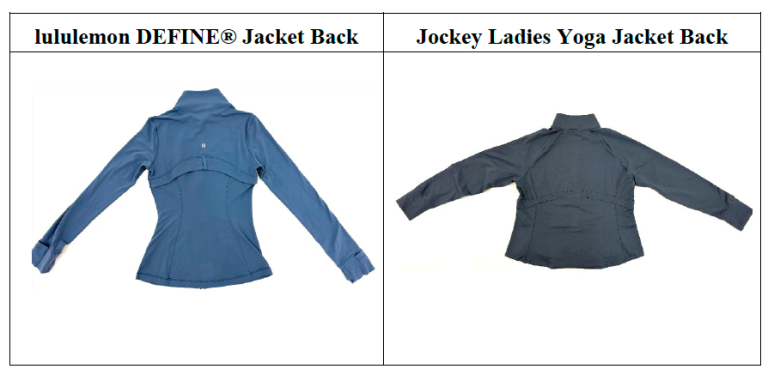

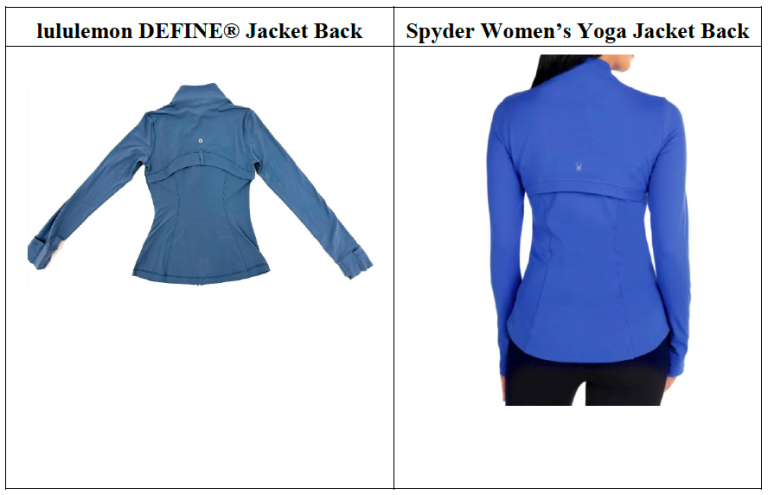

The two products Lululemon accuses of infringing its rights in the DEFINE jacket are the Jockey Ladies Yoga Jacket and the Spyder Women’s Yoga Jacket, shown below side by side with the Lululemon jacket.

The horizontal curved line on the front of the DEFINE jacket is absent from the Jockey jacket and appears much lower on the Spyder jackets; the vertical curved lines are present on both, but slightly different. The horizontal curved line on the back of the DEFINE jacket is much straighter on the Spyder jacket and appears on a different spot on the Jockey one. Would either jacket create a likelihood of consumer confusion, considering not just the jackets’ similarities but also their different price points, retail channels, and distinguishing brand names?

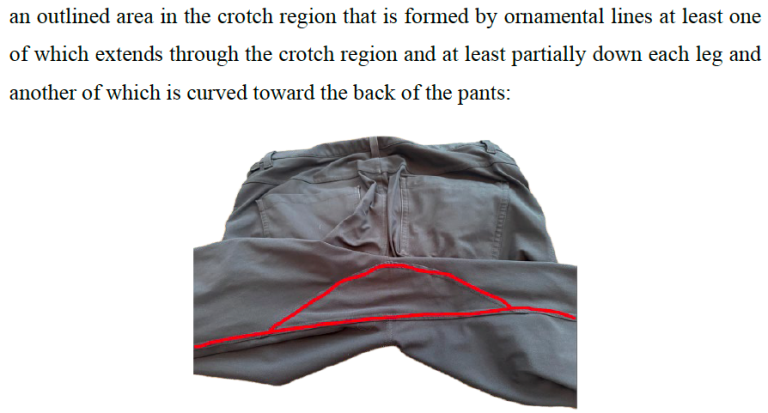

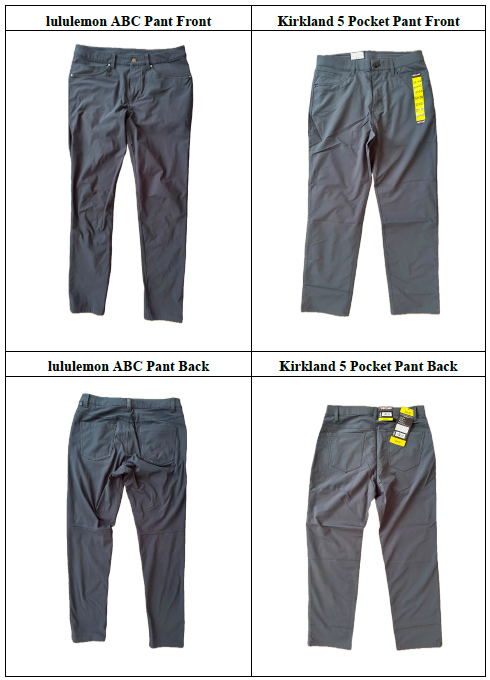

Lululemon also asserts rights in its ABC pant. Unlike the sweatshirt and jacket, there are no registered trademark, trade dress, or design patent rights for this one—just common law rights, or as Lululemon grandly puts it, “extensive common law rights in the distinctive overall appearance and holistic design of its ABC pants.” The claimed trade dress comprises a semi-matte fabric with four-direction stretch, an “outlined area in the crotch region,” an “ornamental line extending across the rear of the pants,” and curved lines around the front pockets with metallic circles. As one of us told the Associated Press, this assertion of rights seemed like a stretch (pun intended). Is Lululemon really asserting that a curved triangle seam on the crotch of a pair of pants is non-functional, indicates source to consumers, and has acquired sufficient distinctiveness to merit exclusive rights? Can the company argue with a straight face that this matter is visible in a trademark space—a place consumers expect to see source-indicating matter?

Here, as with its other asserted products, Lululemon points to advertising for the pants, television appearances, celebrities seen wearing them (including President Obama!), and third-party media coverage. But the case law makes clear that establishing acquired distinctiveness for trade dress features is more complicated. Typically it requires “look-for advertising” that draws attention to the features claimed, rather than just sales, general advertising, and consumer familiarity with the overall product. The Lululemon pant and the Kirkland pant may look similar—they may be similar—but we are skeptical that a court or jury would find protectable elements in the first place or that Kirkland’s use of similar features could be found to create a likelihood of confusion.

The final set of products in which Lululemon asserts rights—including trade dress, trademark, and design patent rights—are the Scuba hoodies and sweatshirts. Its asserted common law trade dress covers the shape and design of the kangaroo pocket and curved lines on the front of the garment, highlighted in the complaint in red:

With this trade dress too, we can foresee arguments about functionality, distinctiveness, and failure to function as a mark. Because it is unregistered, Lululemon will bear the burden of establishing protectability.

The company also owns a federal registration for SCUBA for use in connection with hooded sweatshirts, jackets, coats, and tops. One of the sweatshirts that Costco sells is designated “Hi-Tec Men’s Scuba Full Zip,” which Lululemon argues infringes its SCUBA trademark. A quick Google search, though, yields many results for “scuba” sweatshirts or garments with “scuba” pockets from a number of different brands, implying that perhaps the term is generic for certain clothing items or styles or descriptive enough that Costco’s use might qualify as a fair use.

Lululemon also alleges common law trademark rights in TIDEWATER TEAL for a variety of products, including apparel and a belt bag, and claims that Costco has advertised and sold some of its Danskin Half-Zip Pullovers using the phrase “tidewater teal.” Assuming the Danskin pullover is teal in color, there’s a fair use argument to be made here as well. But “tidewater teal” is a lot more specific than “teal” and seems too specific to be a coincidence. A court or jury might also find that even if those uses of “scuba” and “tidewater teal” in isolation aren’t enough to support infringement claims, in the context of the similar items with which they’re used, they provide evidence of bad faith and an effort to optimize search engine results and trade on confusion. Lululemon can tell a story that consumers seeking out the Lululemon Tidewater Teal SCUBA product are likely to be led straight to the Danskin pullover in tidewater teal available at Costco, increasing the likelihood of confusion (remember the story the Ninth Circuit told in MTM v. Amazon (before subsequently reversing itself) about the consumer searching for “MTM Special Ops watches” for her brother and buying the wrong one?).

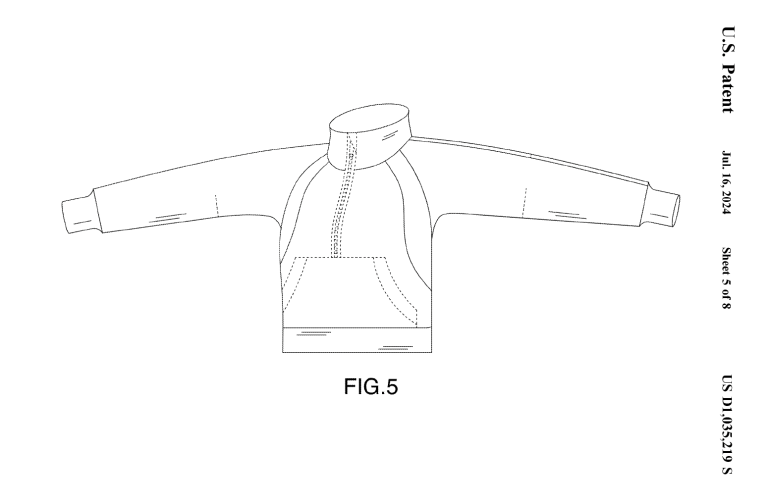

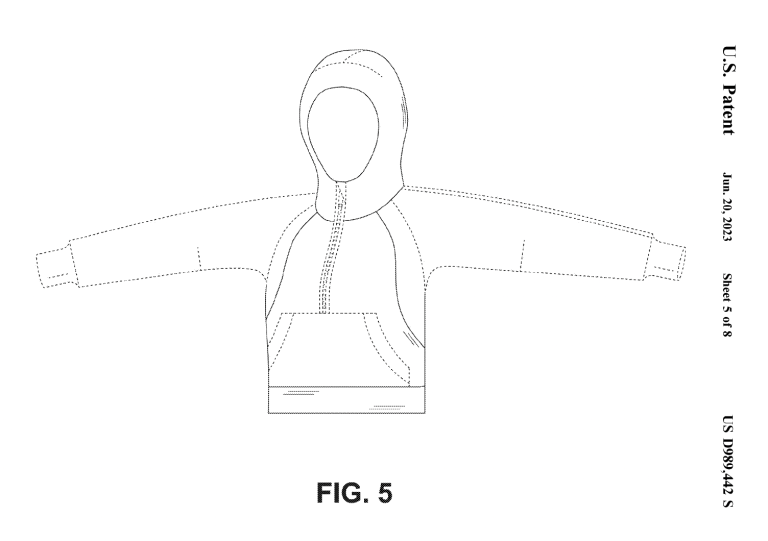

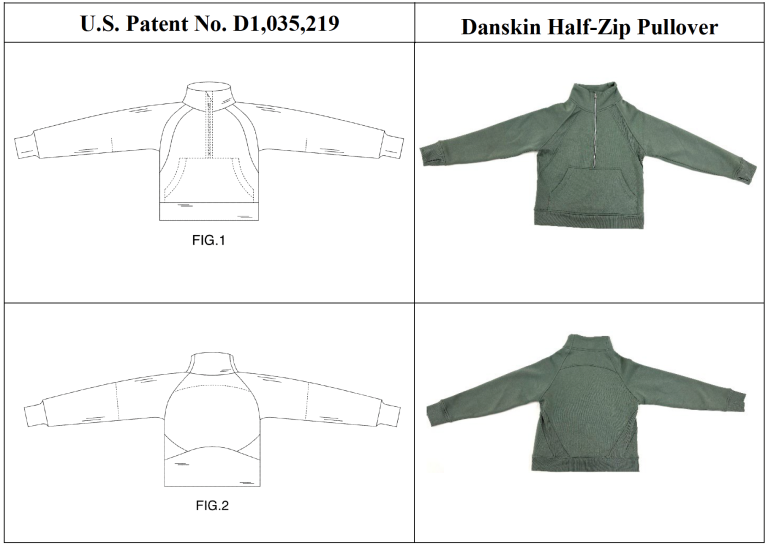

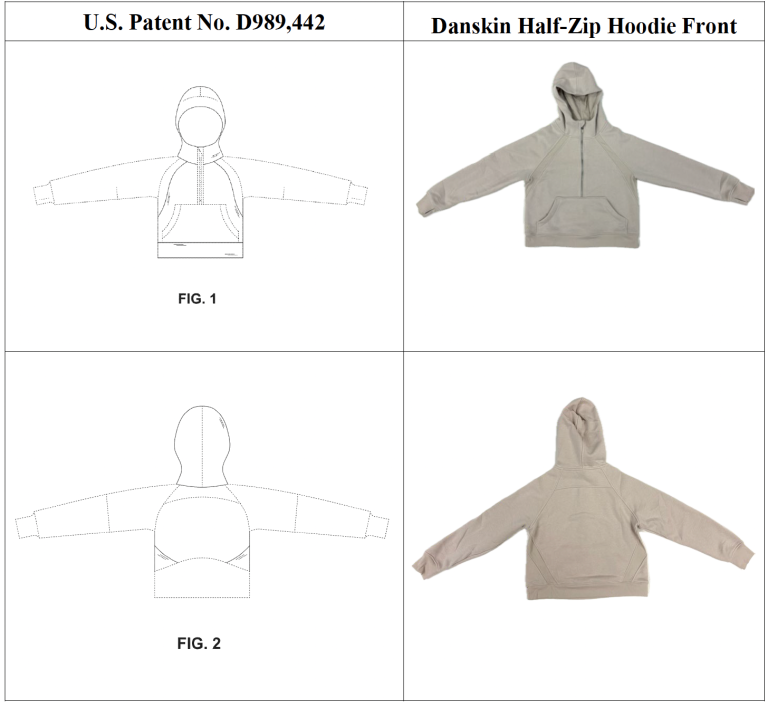

In addition to its trademark and trade dress claims about the Scuba sweatshirt, Lululemon also asserts infringement of two design patents.

Design patents are different from trademarks. The test for design patent infringement is, basically: Does the accused product look the same, in all relevant respects, to the claimed design? Let’s break that down a bit.

We start by looking at the claim. The design patents here both claim designs for garments. But they cover different garments and vary in scope.

A design patent covers what is shown in solid lines in the drawings. Anything shown in dotted lines is not part of the claimed design.

Here is a representative image from the D’219 patent. As you can see, it covers a jacket or sweater-like design without a hood. The zipper and the front pocket are disclaimed:

In the context of this case, those disclaimer lines mean that, for the purposes of infringement, the factfinder has to look at the appearance of everything but the zipper and the front pocket. If all the parts of an accused product look the same as the parts shown here in solid lines look the same, the patent will be infringed.

In the D’442 patent, there is a claimed hood but the arms are disclaimed, as well as the zipper and front pocket:

So this patent is infringed if an accused garment has the same hood shape, curved lines across the chest, bottom band, and anything else shown in solid lines.

Importantly, the test for design patent infringement—unlike trade dress infringement—does not consider whether consumers would be confused as to the source, sponsorship or approval of the garments. All that matters is visual similarity. (For those who would like a larger explanation of this point, see Part I(B)(1) of this article.) And although design patent cases use the phrase “substantially similar” to refer to the infringement standard, the test is very different than the “substantial similarity” required in copyright law. (Id. at n.64.)

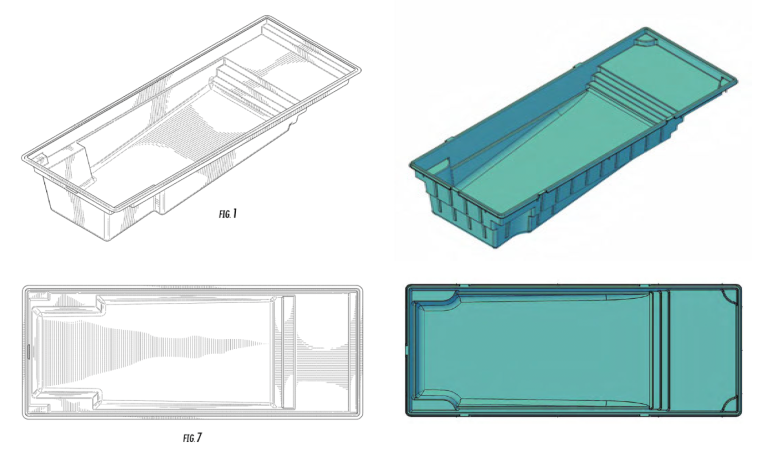

And the degree of visual similarity required is high. For example, the Federal Circuit recently affirmed a district court’s decision that the pool design shown below on the right did not infringe the design shown below on the left:

This is consistent with the court’s prior decisions.

So, first we compare the claimed design to the accused product. If the designs are “sufficiently distinct that it will be clear without more that the patentee has not met its burden of proving the two designs would appear ‘substantially the same’ to the ordinary observer,” then the case is over; there is no infringement. Egyptian Goddess, Inc. v. Swisa, Inc., 543 F.3d 665, 678 (Fed. Cir. 2008) (en banc).

If the designs are not “plainly dissimilar,” then—and only then—the factfinder can consider the prior art in the analysis. Id. Importantly, the prior art cannot be used to expand the presumptive scope of the design patent. See Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc. v. Covidien, Inc., 796 F.3d 1312, 1337 (Fed. Cir. 2015) (rejecting a patentee’s attempt to do that). It can only be used to narrow the presumptive scope of the claim where the claimed and accused designs are already visually close. (For some visual examples, see Chapter 12 here.)

Now, let’s look at Lululemon’s infringement claims. The complaint contains these images showing the D’219 patent and an accused product. Recall that the shape of the front pocket and the shape of the zipper don’t matter here—we look only at what is shown in solid lines.

A court applying the Egyptian Goddess test might well decide this accused product is plainly dissimilar and end the analysis there. While the design concepts here are similar, the actual design differs in a number of not immaterial respects. For example, the main visual design element on the front—the pieced portions extending from the neck to the underarm areas—are notably different shapes. In the Lululemon design, they’re curved. In the accused design, they’re not. The curves on the back have the same issue. And the wedge-shapes on the back are also noticeably different. That’s enough to defeat a finding of infringement.

The hoodie claim suffers from the same issues:

This patent also raises another issue: The shape of the hood. It’s difficult to accurately depict the shapes of certain soft articles with line drawings. But based just on these drawings, the hoods may also differ in visually meaningful ways.

These accused products are certainly similar, at a conceptual level, to the Lululemon designs. But that’s not enough to infringe the patents.

One might ask whether validity is an issue here. After all, patentable designs are supposed to be novel, nonobvious, and ornamental. The statutory requirements might sound difficult to meet but, in practice, they are not. (See here and here.) The Federal Circuit’s 2024 en banc decision in LKQ v. GM gives Costco new arguments that they could make if they wanted to challenge one or both designs as nonobvious. But it’s not yet whether these new arguments—and the new LKQ standard—will actually result in more successful obviousness challenges.

At this point, readers who have stuck with us this far (thank you!) may be asking: But didn’t Costco copy Lululemon? Quite possibly! But even if Costco copied, that doesn’t mean that it infringed any of the IP rights asserted here. At the same time, this lawsuit seems to have inspired a lot of interest—in the Costco products. Other brand owners thinking about taking similar enforcement actions might want to spend some time meditating on that.