A Takedown of the Take It Down Act

By guest blogger Prof. Jess Miers (with additional comments from Eric)

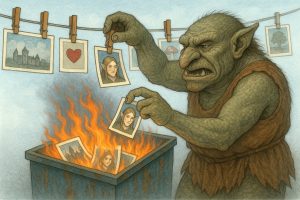

Two things can be true: Non-consensual intimate imagery (NCII) is a serious and gendered harm. And, the ‘Tools to Address Known Exploitation by Immobilizing Technological Deepfakes on Websites and Networks Act,’’ a/k/a the TAKE IT DOWN Act, is a weapon of mass censorship.

Background

In October 2023, two high school students became the victims of AI-generated NCII. Classmates had used “nudify” tools to create fake explicit images using public photos pulled from their social media profiles. The incident sparked outrage, culminating in a hearing last June where the students’ families called for federal action.

Congress responded with the TAKE IT DOWN Act, introduced by Senator Ted Cruz and quickly co-sponsored by a bipartisan group of lawmakers. On its face, the law targets non-consensual intimate imagery, including synthetic content. In practice, it creates a sweeping speech-removal regime with few safeguards.

Keep in mind, the law was passed under an administration that has shown little regard for civil liberties or dissenting speech. It gives the government broad power to remove online content of which it disapproves and opens the door to selective enforcement. Trump made his intentions clear during his March State of the Union:

And I’m going to use that bill for myself too, if you don’t mind—because nobody gets treated worse than I do online.

Some interpreted this as a reference to a viral AI-generated video of Trump kissing Elon Musk’s feet—precisely the kind of political satire that could be subject to removal under the Act’s broad definitions.

The bill moved unusually fast compared to previous attempts at online speech regulation. It passed both chambers without a single amendment, despite raising serious First Amendment and due process concerns. Following the TikTok ban, it marks another example of Congress enacting sweeping online speech restrictions with minimal debate and virtually no public process.

Senator Booker briefly held up the bill in mid-2024, citing concerns about vague language and overbroad criminal penalties. After public backlash, including pressure from victims’ families, Senator Booker negotiated a few modest changes. The revised bill passed the Senate by unanimous consent in February 2025. The House advanced it in April, ignoring objections from civil liberties groups and skipping any real markup.

President Trump signed the TAKE IT DOWN Act into law in May. The signing ceremony made it seem even more like a thinly veiled threat toward online services that facilitate expression, rather than a legitimate effort to curb NCII. At the ceremony, First Lady Melania Trump remarked:

Artificial Intelligence and social media are the digital candy of the next generation—sweet, addictive, and engineered to have an impact on the cognitive development of our children. But unlike sugar, these new technologies can be weaponized, shape beliefs, and sadly, affect emotions and even be deadly.

And just recently, FTC Chair Andrew Ferguson—handpicked by Trump and openly aligned with his online censorship agenda—tweeted his enthusiasm about enforcing the TAKE IT DOWN Act in coordination with the Department of Homeland Security. Yes, the same agency that has been implicated in surveilling protestors and disappearing U.S. citizens off the streets during civil unrest.

Statutory Analysis

Despite overwhelming (and shortsighted) support from the tech industry, the TAKE IT DOWN Act spells trouble for any online service that hosts third-party content.

The law contains two main provisions: one criminalizing the creation, publication, and distribution of authentic, manipulated, and synthetic NCII, and another establishing a notice-and-takedown system for online services hosting NCII that extends to a potentially broader range of online content.

Section 2: Criminal Prohibition on Intentional Disclosure of Nonconsensual Intimate Visual Depictions

Section 2 of the Act creates new federal criminal penalties for the publication of non-consensual “intimate visual depictions,” including both real (“authentic”) and technologically manipulated or AI-generated imagery (“digital forgeries”). These provisions are implemented via amendments to Section 223 of the Communications Act and took effect immediately upon enactment.

Depictions of Adults

The statute applies differently depending on whether the depiction involves an adult or a minor. With respect to depicting adults, it is a federal crime to knowingly publish an intimate visual depiction via an interactive computer service (as defined under Section 230) if the following are met: (1) the image was created or obtained under circumstances where the subject had a reasonable expectation of privacy; (2) the content was not voluntarily exposed in a public or commercial setting; (3) the image is not of public concern; and (4) the publication either was intended to cause harm or actually caused harm (defined to include psychological, financial, or reputational injury).

The statute defines “intimate visual depictions” via 15 U.S.C. § 6851. The definition includes images showing uncovered genitals, pubic areas, anuses, or post-pubescent female nipples, as well as depictions involving the display or transfer of sexual fluids. Images taken in public may still qualify as “intimate” if the individual did not voluntarily expose themselves or did not consent to the sexual conduct depicted.

In theory, the statute exempts pornography that was consensually produced and distributed online. In practice, the scope of that exception is far from clear. One key requirement for triggering criminal liability in cases involving adults is that “what is depicted was not voluntarily exposed by the identifiable individual in a public or commercial setting.” The intent seems to be to exclude lawful adult content from the law’s reach.

But the language is ambiguous. The statute refers to what is depicted—potentially meaning the body parts or sexual activity shown—rather than to the image itself. Under this reading, anyone who has ever publicly or commercially shared intimate content generally could be categorically excluded from protection under the law, even if a particular image was created or distributed without their consent. That interpretation would effectively deny coverage to adult content creators and sex workers, the very individuals who are often most vulnerable to nonconsensual republishing and exploitation of their content.

Depictions of Children

With respect to depictions of minors, the TAKE IT DOWN Act criminalizes the distribution of any image showing uncovered genitals, pubic area, anus, or female-presenting nipple—or any depiction of sexual activity—if shared with the intent to abuse, humiliate, harass, degrade, or sexually gratify.

Although the Act overlaps with existing federal child sexual abuse material (CSAM) statutes, it discards the constitutional boundaries that have kept those laws from being struck down as unconstitutional. Under 18 U.S.C. § 2256(8), criminal liability attaches only to depictions of “sexually explicit conduct,” a term courts have narrowly defined to include things like intercourse, masturbation, or lascivious exhibition of genitals. Mere nudity doesn’t typically qualify, at least not without contextual cues. Even then, prosecutors must work to show that the image crosses a clear, judicially established threshold.

TAKE IT DOWN skips the traditional safeguards that typically constrain speech-related criminal laws. It authorizes felony charges for publishing depictions of minors that include certain body parts if done with the intent to abuse, humiliate, harass, degrade, arouse, or sexually gratify. But these intent standards are left entirely undefined. A family bathtub photo shared with a mocking or off-color caption could be framed as intended to humiliate or, in the worst-case reading, arouse. A public beach photo of a teen, reposted with sarcastic commentary, might be interpreted as degrading. Of course, these edge cases should be shielded by traditional First Amendment defenses.

We’ve seen this before. Courts have repeatedly struck down or narrowed CSAM laws that overreach, particularly when they criminalize nudity or suggestive content that falls short of actual sexual conduct, such as family photos, journalism, documentary film, and educational content.

TAKE IT DOWN also revives the vagueness issues that have plagued earlier efforts to curb child exploitation online. Terms like “harass,” “humiliate,” or “gratify” are inherently subjective and undefined, which invites arbitrary enforcement. In effect, the law punishes speakers based on perceived motive rather than the objective content itself.

Yes, the goal of protecting minors is laudable. But noble intentions don’t save poorly drafted laws. Courts don’t look the other way when speech restrictions are vague or overbroad just because the policy behind them sounds good. If a statute invites constitutional failure, it doesn’t end up protecting anyone. In short, the TAKE IT DOWN Act replicates the very defects that have led courts to limit or strike down earlier child-protection laws.

Digital Forgeries

The statute also criminalizes the publication of “digital forgeries” without the depicted person’s consent, which differs from the “reasonable expectation of privacy” element for authentic imagery. A digital forgery is defined as any intimate depiction created or altered using AI, software, or other technological means such that it is, in the eyes of a reasonable person, indistinguishable from an authentic image. This standard potentially sweeps in a wide range of synthetic and altered content, regardless of whether a viewer actually believed the image was real or whether the underlying components were independently lawful.

Compared to existing CSAM laws, the TAKE IT DOWN Act also uses a more flexible visual standard when it comes to “digital forgeries.” Under CSAM law, synthetic or computer-generated depictions are only criminalized if they are “indistinguishable from that of a real minor engaging in sexually explicit conduct.” That standard makes it difficult to prosecute deepfakes or AI nudes unless they are photorealistic and sexually explicit. But under TAKE IT DOWN, a digital forgery is covered if it “when viewed as a whole by a reasonable person, is indistinguishable from an authentic visual depiction of the individual.” The focus isn’t on whether the depiction looks like a real child in general, but whether it looks like a real, identifiable person. This makes the law far more likely to apply to a broader range of AI-generated depictions involving minors, even if the underlying content wouldn’t meet the CSAM threshold. As discussed in the implications section, this too invites First Amendment scrutiny.

There are several exceptions. The statute does not apply to disclosures made as part of law enforcement or intelligence activity, nor to individuals acting reasonably and in good faith when sharing content for legitimate legal, medical, educational, or professional purposes. The law also exempts people sharing intimate content of themselves (as long as it contains nudity or is sexual in nature) and content already covered by federal CSAM laws.

Penalties include fines and up to two years’ imprisonment for adult-related violations, and up to three years for violations involving minors. Threats to publish such material can also trigger criminal liability.

Finally, the Act leaves unanswered whether online services could face criminal liability for failing to remove known instances of authentic or AI-generated NCII. Because Section 230 never applies to federal criminal prosecutions, intermediaries cannot rely on it as a defense against prosecution. If a service knowingly hosts unlawful material, including not just NCII itself, but threats to publish it, such as those made in private messages, the government may claim the service is “publishing” illegal content in violation of the statute.

The Supreme Court’s decision in Taamneh provides some insulation. It held that general awareness of harmful conduct on a service does not amount to the kind of specific knowledge required to establish aiding-and-abetting liability. But the TAKE IT DOWN Act complicates that picture. Once a service receives a takedown request for a particular image, it arguably acquires actual knowledge of illegal content. If the service fails to act within the Act’s 48-hour deadline, it’s not clear whether that inaction could form the basis for a criminal charge under the statute’s separate enforcement provisions.

As Eric discusses below, there’s also no clear answer to what happens when someone re-uploads content that had previously been removed (or even new violating content). Does prior notice of a particular individual’s bad acts create the kind of ongoing knowledge that turns continued hosting into criminal publication? That scenario falls into a legal gap narrower than Taamneh might account for, but the statute doesn’t clarify how courts should treat repeat violations.

Section 3: Notice and Removal of Nonconsensual Intimate Visual Depictions

Alongside its criminal provisions, the Act imposes new civil compliance obligations on online services that host user-generated content. Covered services must implement a notice-and-takedown process to remove intimate visual depictions (real or fake) within one year of the law’s enactment. The process must allow “identifiable individuals” or their authorized agents to request removal of non-consensual intimate images. Once a valid request is received, the service has 48 hours to remove the requested content. Failure to comply subjects the service to enforcement by the Federal Trade Commission under its unfair or deceptive practices authority.

The law applies to any public-facing website, app, or online service that primarily hosts user-generated content—or, more vaguely, services that “publish, curate, host, or make available” non-consensual intimate imagery as part of their business. This presumably includes social media services, online pornography services, file-sharing tools, image boards, and arguably even private messaging apps. It likely includes search engines as well, and the “make available” standard could apply to user-supplied links to other sites. Notably, the law excludes Internet access providers, email services, and services where user-submitted content is “incidental” to the service’s primary function. This carveout appears designed to protect online retailers, streaming services like Netflix, and news media sites with comment sections. However, the ambiguity around what qualifies as “incidental” will likely push services operating in the gray zone toward over-removal or disabling functionality altogether.

Generative AI tools likely fall within the scope of the law. If a system generates and displays intimate imagery, whether real or synthetic, at a user’s direction, it could trigger takedown obligations. However, the statute is silent on how these duties apply to services that don’t “host” content in the traditional sense. In theory, providers could remove specific outputs if stored, or even retrain the model to exclude certain images from its dataset. But this becomes far more complicated when the model has already “memorized” the data and internalized it into its parameters. As with many recent attempts to regulate AI, the hard operational questions—like how to unwind learned content—are left unanswered, effectively outsourced to developers to figure out later.

Though perhaps inspired by the structure of existing notice-and-takedown regimes, such as the DMCA’s copyright takedown framework, the implementation here veers sharply from existing content moderation norms. A “valid” TAKE IT DOWN request requires four components: a signature, a description of the content, a good faith statement of non-consent, and contact information. But that’s where the rigor ends.

There is no requirement to certify a takedown request under penalty of perjury, nor any legal consequence for impersonating someone or falsely claiming to act on their behalf. The online services, not the requester, bear the burden of verifying the identity of both the requester and the depicted individual, all within a 48-hour window. In practice, most services will have no realistic option other than to take the request at face value and remove the content, regardless of whether it’s actually intimate or non-consensual. This lack of verification opens the door to abuse, not just by individuals but by third-party services. There is already a cottage industry emerging around paid takedown services, where companies are hired to scrub the Internet of unwanted images by submitting removal requests on behalf of clients, whether authorized or not. This law will only bolster that industry.

The law also only requires a “reasonably sufficient” identification of the content. There’s no obligation to include URLs, filenames, or specific asset identifiers. It’s unclear whether vague descriptions like “nudes of me from college” are sufficient to trigger a takedown obligation. Under the DMCA, this level of ambiguity would likely invalidate a request. Here, it might not only be acceptable, it could be legally actionable to ignore.

The statute’s treatment of consent is equally problematic. A requester must assert that the content was published without consent but need not provide any evidence to support the claim, other than a statement of good faith belief. There is no adversarial process, no opportunity for the original uploader to dispute the request, and no mechanism to resolve conflicts where the depicted person may have, in fact, consented. In cases where an authorized agent submits a removal request on someone’s behalf (say, a family member or advocacy group), it’s unclear what happens if the depicted individual disagrees. The law contemplates no process for sorting this out. Services are expected to remove first and ask questions never.

Complicating matters further, the law imposes an obligation to remove not only the reported content but also any “identical copies.” While framed as a measure to prevent whack-a-mole reposting, this provision effectively creates a soft monitoring mandate. Even when the original takedown request is vague or incomplete—which the statute permits—services are still required to scan their systems for duplicates. This must be done despite often having little to no verification of the requester’s identity, authority, or the factual basis for the alleged lack of consent. Worse, online services must defer to the requester’s characterization of the content, even if the material in question may not actually qualify as an “intimate visual depiction” under the statutory definition.

Lastly, the law grants immunity to online services that remove content in good faith, even if the material doesn’t meet the definition of an intimate visual depiction. This creates a strong incentive to over-remove rather than assess borderline cases, especially when the legal risk for keeping content up outweighs any penalty for taking it down.

(Notably, neither the criminal nor civil provisions of the law expressly carve-out satirical, parody, or protest imagery that happens to involve nudity or sexual references.)

* * *

Some implications of the law:

Over-Criminalization of Legal Speech

The law creates a sweeping new category of criminalized speech without the narrow tailoring typically required for content-based criminal statutes. Language surrounding “harm,” “public concern,” and “reasonable expectation of privacy” invite prosecutorial overreach and post-hoc judgments about whether a given depiction implicates privacy interests and consent, even when the speaker may have believed the content was lawful, newsworthy, or satirical.

The statute allows prosecution not only where the speaker knew the depiction was private, but also where they merely should have known. This is a sharp departure from established First Amendment doctrine, which requires at least actual knowledge or reckless disregard for truth in civil defamation cases, let alone criminal ones.

The law’s treatment of consent raises unresolved questions. It separates consent to create a depiction from consent to publish it, but says nothing about what happens when consent to publish is later withdrawn. A person might initially agree to share a depiction with a journalist, filmmaker, or content partner, only to later revoke that permission. The statute offers no clarity on how that revocation must be communicated and whether it must identify specific content versus a general objection.

To be clear, the statute requires that the speaker “knowingly” publish intimate imagery without consent. So absent notice of revocation, criminal liability likely wouldn’t attach. But what counts as sufficient notice? Can a subject revoke consent to a particular use or depiction? Can they revoke consent across the board? If a journalist reuses a previously approved depiction in a new story, or a filmmaker continues distributing a documentary after one subject expresses discomfort, are those “new” publications requiring fresh consent? The law provides no mechanism for resolving these questions.

Further, for adult depictions, the statute permits prosecution where the publication either causes harm or was intended to cause harm. This opens the door to criminal liability based not on the content itself, but on its downstream effects, regardless of whether the speaker acted in good faith. The statute includes no explicit exception for newsworthiness, artistic value, or other good-faith purposes, nor does it provide any formal opportunity for a speaker to demonstrate the absence of malicious intent. In theory, the First Amendment (and Taamneh) should cabin the reach, but the text itself leaves too much room for prosecutorial discretion.

The law also does not specify whether the harm must be to the depicted individual or to someone else, leaving open the possibility that prosecutors could treat general moral offense, such as that invoked by anti-pornography advocates, as sufficient. The inclusion of “reputational harm” as a basis for criminal liability is especially troubling. The statute makes no distinction between public and private figures and requires neither actual malice nor reckless disregard, setting a lower bar than what’s required even for civil defamation.

Further, because the law criminalizes “digital forgeries,” and defines them broadly to include any synthetic content indistinguishable, to a reasonable person, from reality, political deepfakes are vulnerable to prosecution. A video of a public official in a compromising scenario, even if obviously satirical or critical, could be treated as a criminal act if the depiction is deemed sufficiently intimate and the official claims reputational harm. [FN] The “not a matter of public concern” carveout is meant to prevent this, but it’s undefined and thus subject to prosecutorial discretion. Courts have repeatedly struggled to draw the line between private and public concern, and the statute offers no guidance.

[FN: Eric’s addition: I call this the Anthony Weiner problem, where his sexting recipients’ inability to prove their claims by showing the receipts would have allowed Weiner to lie without accountability.]

This creates a meaningful risk that prosecutors, particularly those aligned with Trump, could weaponize the law against protest art, memes, or critical commentary. Meta’s prior policy, for example, permitted images of a visible anus or close-up nudity if photoshopped onto a public figure for commentary or satire. Under the TAKE IT DOWN Act, similar visual content could become a target for prosecution or removal, especially when it involves politically powerful individuals. The statute provides plenty of wiggle room for selective enforcement, producing a chilling effect for creators, journalists, documentarians, and artists who work with visual media that is constitutionally protected but suddenly carries legal risk under this law.

With respect to depictions of minors, the law goes further: a person can be prosecuted for publishing an intimate depiction if they did so with the intent to harass or humiliate the minor or arouse another individual. As discussed, the definition of intimate imagery covers non-sexually explicit content, which covers content that is likely broader than existing CSAM or obscenity laws. This means that the law creates a lower-tier criminal offense for visual content involving minors, even if the images are not illegal under current federal law.

For “authentic” images, the law could easily reach innocent but revealing photos of minors shared online. As discussed, if a popular family content creator posts a photo of their child in the bathtub (content that arguably shouldn’t be online in the first place) and the government concludes the poster intended to arouse someone else, that could trigger criminal liability under the TAKE IT DOWN Act. Indeed, family vloggers have repeatedly been accused of curating “innocent” content to appeal to their adult male followers as a means of increasing engagement and revenue, despite pushback from parents and viewers. (Parents may be part of the problem). While the underlying content itself is likely legal speech to the extent it doesn’t fall within CSAM or obscenity laws, it could still qualify as illegal content, subject to criminal prosecution, under the Act.

For AI-generated images, the law takes an even more aggressive approach for minors. Unlike federal CSAM laws, which only cover synthetic images that are “indistinguishable” from a real minor, the TAKE IT DOWN Act applies to any digital forgery that, in the eyes of a reasonable person, appears to depict a specific, identifiable child. That’s a significant shift. The higher standard in CSAM law was crafted to comply with Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition, where the Supreme Court struck down a federal ban on virtual CSAM that wasn’t tied to real individuals. The Court’s rationale protected fictional content, including cartoon imagery (think a nude depiction of South Park’s Eric Cartman) as constitutionally protected speech. By contrast, the TAKE IT DOWN Act abandons that distinction and criminalizes synthetic content based on how it appears to a reasonable viewer, not whether it reflects reality or actual harm. That standard is unlikely to survive Ashcroft-level scrutiny and leaves the law open to serious constitutional challenge.

Disproportionate Protections & Penalties For Vulnerable Groups

The TAKE IT DOWN Act is framed as a measure to protect vulnerable individuals, such as the high school students victimized by deepfake NCII. Yet its ambiguities risk leaving some vulnerable groups unprotected, or worse, exposing them to prosecution.

The statute raises the real possibility of criminalizing large numbers of minors. Anytime we’re talking about high schoolers and sharing of NCII, we have to ask whether the law applies to teens who forward nudes—behavior that is unquestionably harmful and invasive, but also alarmingly common (see, e.g., 1, 2, 3). While the statute is framed as a tool to punish adults who exploit minors, its broad language easily sweeps in teenagers navigating digital spaces they may not fully understand. Yes, teens should be more careful with what they share, but that expectation doesn’t account for the impulsiveness, peer pressure, and viral dynamics that often define adolescent behavior online. A nude or semi-nude image shared consensually between peers can rapidly spread beyond its intended audience. Some teens may forward it not to harass or humiliate, but out of curiosity or simply because “everyone else already saw it.” Under the TAKE IT DOWN Act, that alone could trigger federal criminal liability.

With respect to depictions of adults, the risks are narrower but still present. The statute specifies that consent to create a depiction does not equate to consent to publish it, and that sharing a depiction with someone else does not authorize them—or anyone else—to republish it. These provisions are intended to close familiar NCII loopholes, but they also raise questions about how the law applies when individuals post or re-share depictions of themselves. There is no broad exemption for self-publication by adults, only the same limited carveout for depictions involving nudity or sexual conduct. That may cover much of what adult content creators publish, but it leaves unclear how the law treats suggestive or partial depictions that fall short of statutory thresholds. In edge cases, a prosecutor could argue that a self-published image lacks context-specific consent or causes general harm, especially if the prosecutor is inclined to target adult content as a matter of policy.

At the same time, the law seems to also treat adult content creators and sex workers as effectively ineligible for protection. As discussed, prior public or commercial self-disclosure potentially disqualifies someone from being a victim of non-consensual redistribution. Instead of accounting for the specific risks these communities face, the law appears to treat them as discardable (as is typical for these communities).

This structural asymmetry is made worse by the statute’s sweeping exemption for law enforcement and intelligence agencies, despite their well-documented misuse of intimate imagery. Police have used real sex workers’ photos in sting operations without consent, exposing individuals to reputational harm, harassment, and even false suspicion. A 2021 DOJ Inspector General report found that FBI agents, while posing as minors online, uploaded non-consensual images to illicit websites. This is conduct that violated agency policy but seems to be fully exempt under Take It Down. This creates a feedback loop: the state appropriates private images, recirculates them, and then uses the fallout as investigative justification.

Over-Removal of Political Speech, Commentary, and Adult Content

Trump and his allies have a long track record of attempting to suppress unflattering or politically inconvenient content. Under the civil takedown provisions of the TAKE IT DOWN Act, they no longer need to go through the courts to do it. All it takes is an allegation that a depiction violates the statute. Because the civil standard is more permissive, that allegation doesn’t have to be well-founded, it just has to allege that the content is an “intimate visual depiction.” A private photo from a political fundraiser, a photoshopped meme using a real image, or an AI-generated video of Trump kissing Elon Musk’s feet could all be flagged under the law, even if they don’t meet the statute’s actual definition. But here’s the catch: services have just 48 hours to take the content down. That’s not 48 hours to investigate, evaluate, or push back, it’s 48 hours to comply or risk FTC enforcement. In practice, that means the content is far more likely to be removed than challenged, especially when the requester claims the material is intimate. Services will default to caution, pulling content that may not meet the statutory threshold just to avoid regulatory risk. As we saw after FOSTA-SESTA, that kind of liability pressure drives entire categories of speech offline.

Moreover, the provision requiring online services to remove identical copies of the reported content, in practice, might encourage online services to take a scorched-earth approach to removals: deleting entire folders, wiping user accounts, pulling down all images linked to a given name or metadata tag, or even removing the contents of an entire website. It’s easy to see how this could be especially weaponized against adult content sites, where third-party uploads often blur the line between lawful adult material and illicit content.

Further, automated content moderation tools that are designed to efficiently remove content while shielding human workers from exposure harms may exacerbate the issue. Many online services use automated classifiers, blurred previews, and image hashing systems to minimize human exposure to disturbing content. But the TAKE IT DOWN Act requires subjective judgment calls that automation may not be equipped to make. Moderators must decide whether a depiction is truly intimate, whether it falls under an exception, whether the depicted individual voluntarily exposed themselves, and whether the requester is legitimate. These are subjective, context-heavy determinations that require viewing the content directly. In effect, moderators are now pushed back into frontline exposure just to determine if a depiction meets the statute’s definition.

The enforcement provisions of the TAKE IT DOWN Act give the federal government—particularly a politicized FTC delighting in its newfound identity as a censorship board—broad discretion to target disfavored online services. A single flagged depiction labeled a digital forgery can trigger invasive investigations, fines, or even site shutdowns. Recall that The Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 mandate explicitly calls for the elimination of online pornography. This law offers a ready-made mechanism to advance that agenda, not only for government officials but also for aligned anti-pornography groups like NCOSE. Once the state can reframe consensual adult content as non-consensual or synthetic, regardless of whether that claim holds, it can begin purging lawful material from the Internet under the banner of victim protection.

This enforcement model will also disproportionately affect LGBTQ+ content, which is already subject to heightened scrutiny and over-removal. Queer creators routinely report that their educational, artistic, or personal content is flagged as adult or explicit, even when it complies with existing community guidelines. Under the TAKE IT DOWN Act, content depicting queer intimacy, gender nonconformity, or bodies outside heteronormative standards could be more easily labeled as “intimate visual depictions,” especially when framed by complainants as inappropriate or harmful. For example, a shirtless trans-identifying person discussing top surgery could plausibly be flagged for removal. Project 2025 and its enforcers have already sought to collapse LGBTQ+ expression into a broader campaign against “pornography.” The TAKE IT DOWN Act gives that campaign a fast-track enforcement mechanism, with no real procedural safeguards to prevent abuse.

Selective Enforcement By Trump’s FTC

The Act’s notice-and-takedown regime is enforced by the FTC, an agency with no meaningful experience or credibility in content moderation. That’s especially clear from its attention economy workshop, which appear stacked with ideologically driven participants and conspicuously devoid of legitimate experts in Internet law, trust and safety, or technology policy.

The Trump administration’s recent purge and re-staffing of the agency only underscores the point. With internal dissenters removed and partisan loyalists installed, the FTC now functions less as an independent regulator and more as an enforcement tool aligned with the White House’s speech agenda. The agency is fully positioned to implement the law exactly as Trump intends: by punishing political enemies.

We should expect enforcement will not be applied evenly. X (formerly Twitter), under Elon Musk, continues to host large volumes of NCII with little visible oversight. There is no reason to believe a Trump-controlled FTC will target Musk’s services. Meanwhile, smaller, less-connected sites, particularly those serving LGBTQ+ users and marginalized creators, will remain far more exposed to aggressive, selective enforcement.

Undermining Encryption

The Act does not exempt private messaging services, encrypted communication tools, or electronic storage providers. That omission raises significant concerns. Services that offer end-to-end encrypted messaging simply cannot access the content of user communications, making compliance with takedown notices functionally impossible. These services cannot evaluate whether a reported depiction is intimate, harmful, or duplicative because, by design, they cannot see it. See the Doe v. Apple case.

Faced with this dilemma, providers may feel pressure to weaken or abandon encryption entirely in order to demonstrate “reasonable efforts” to detect and remove reported content. This effectively converts private, secure services into surveillance systems, compromising the privacy of all users, including the very individuals the law claims to protect.

The statute’s silence on what constitutes a “reasonable effort” to identify and remove copies of reported imagery only increases compliance uncertainty. In the absence of clear standards, services may overcorrect by deploying invasive scanning technologies or abandoning encryption altogether to minimize legal risk. Weakening encryption in this way introduces systemic security vulnerabilities, exposing user data to unauthorized access, interception, and exploitation. This is particularly concerning as AI-driven cyberattacks become more sophisticated, and as the federal government is actively undermining our nation’s cybersecurity infrastructure.

Conclusion

Trump’s public support for the TAKE IT DOWN Act should have been disqualifying on its own. But even setting that aside, the law’s political and institutional backing should have raised immediate red flags for Democratic lawmakers. Its most vocal champion, Senator Ted Cruz, is a committed culture warrior whose track record includes opposing same-sex marriage, attacking DEI programs, and using students as political props—ironically, the same group this law claims to protect.

The law’s support coalition reads like a who’s who of Christian nationalist and anti-LGBTQ+ activism. Among the 120 organizations backing it are the National Center on Sexual Exploitation (NCOSE), Concerned Women for America Legislative Action Committee, Family Policy Alliance, American Principles Project, and Heritage Action for America. These groups have long advocated for expanded state control over online speech and sexual expression, particularly targeting LGBTQ+ communities and sex workers.

Civil liberties groups and digital rights organizations quickly flagged the law’s vague language, overbroad enforcement mechanisms, and obvious potential for abuse. Even groups who typically support online speech regulation warned that the law was poorly drafted and structurally dangerous, particularly in the hands of the Trump Administration.

At this point, it’s not just disappointing, it’s indefensible that so many Democrats waved this law through, despite its deep alignment with censorship, discrimination, and religious orthodoxy. The Democrats’ support represents a profound failure of both principle and judgment. Worse, it reveals a deeper rot within the Democratic establishment: legislation that is plainly dangerous gets waved through not because lawmakers believe in it, but because they fear bad headlines more than they fear the erosion of democracy itself.

In a FOSTA-SESTA-style outcome, Mr. Deepfakes—one of the Internet’s most notorious hubs for AI-generated NCII and synthetic abuse—shut down before the TAKE IT DOWN Act even took effect. More recently, the San Francisco City Attorney’s Office announced a settlement with one of the many companies it sued for hosting and enabling AI-generated NCII. That litigation has already triggered the shutdown of at least ten similar sites, raising the age-old Internet law question: was this sweeping law necessary to address the problem in the first place?

__

Eric’s Comments

I’m going to supplement Prof. Miers’ comments with a few of my own focused on the titular takedown provision.

The Heckler’s Veto

If a service receives a takedown notice, the service must resolve all of the following tasks within 48 hours:

- Can the service find the targeted item?

- Is anyone identifiable in the targeted item?

- Is the person submitting the takedown notice identifiable in the targeted item?

- Does the targeted item contain an intimate visual depiction of the submitter?

- Did the submitting person consent to the depiction?

- Is the depiction otherwise subject to some privilege? (For example, the First Amendment)

- Can the service find other copies of the targeted item?

- [repeat all of the above steps for each duplicate. Note the copies may be subject to a different conclusion; for example, a copy may be in a different context, like embedded in a larger item of content (like a still image in a documentary) where the analysis might be different]

Alternatively, instead of navigating this gauntlet of short-turnaround tasks, the service can just immediately honor a takedown without any research at all. What would you do if you were running a service’s removals operations? This is not a hard question.

Because the takedown notices are functionally unverifiable and services have no incentive to invest any energy in diligencing them, takedown notices are like the equivalent of heckler’s vetoes. Anyone can submit them knowing that the service will honor them blindly and thereby scrub legitimate content from the Internet. This is a powerful and very effective form of censorship. As Prof. Miers explains, the most likely victims of heckler’s vetoes are communities that are otherwise marginalized.

One caveat: after Moody, it seems likely that laws reducing or eliminating the discretion of editorial services to remove or downgrade non-illegal content, like those contained in the Florida and Texas social media censorship laws, are unconstitutional. If not, the Take It Down Act sets up services for an impossible challenge: they would have to make the right call on the legality of each and every targeted item. Failing to remove illegal content would support a Take It Down FTC enforcement action; removing legal content would set up a claim under the must-carry law. Prof. Miers and I discussed the impossibility of perfectly discerning this border between legal and illegal content.

Bad Design of a Takedown System

The takedown system was clearly designed in reference to the DMCA’s 512 notice-and-takedown scheme. This is not a laudatory attribute. The 512 scheme was poorly designed, which has led to overremovals and consolidated the industry due to the need to achieve economies of scale. The Take It Down Act’s scheme is even more poorly designed. Congress has literally learned nothing from 25 years of experience with the DMCA’s takedown procedures.

Here are some of the ways that the Take It Down Act’s takedown scheme is worse than the DMCA’s:

- As Prof. Miers mentioned, the DMCA requires a high degree of specificity about the location of the targeted item. The Take It Down Act puts more of an onus on the service to find the targeted item in response to imprecise takedown notices.

- The DMCA does not require services to look for and remove identical items, so the Take It Down Act requires services to undertake substantially more work that increases the risk of mistakes and the service’s legal exposure.

- As Prof. Miers mentioned, DMCA notices require the sender to declare, under penalty of perjury, that they are authorized to submit the notice. As a practical matter, I am unaware of any perjury prosecutions actually being brought for DMCA overclaims. Nevertheless, the perjury threat might still motivate some senders to tell the truth. The Take It Down Act doesn’t require such declarations at risk of perjury, which encourages illegitimate takedown notices.

- Further to that point, the DMCA created a new cause of action (512(f)) for sending bogus takedown notices. 512(f) has been a complete failure, but at least it provides some reason for senders to consider if they really want to submit the takedown notice. The Take It Down Act has no analogue to 512(f), so Take It Down notice senders who overclaim may not face any liability or have any reason to curb their actions. This is why I expect lots of robo-notices sent by senders who have no authority at all (such as anti-porn advocates with enough resources to build a robot and a zeal to eliminate adult content online), and I expect many of those robo-notices will be honored without question. This sounds like a recipe for mass chaos…and mass censorship.

- Failure to honor a DMCA takedown notice doesn’t confer liability; it just removes a safe harbor. The Take It Down Act imposes liability for failure to honor a takedown notice two ways: the FTC can enforce that non-removal, plus the risk that the failed removal will support a federal criminal prosecution.

- The DMCA tried to motivate services to provide an error-correction mechanism to uploaders who are wrongly targeted by takedown notices–the 512(g) putback mechanism provides the service with an immunity for restoring targeted content. The Take It Down Act has no error-correction mechanism, either via carrots or sticks, so any correction of bogus removals will be based purely on the service’s good graces.

- The Take It Down Act tries to motivate services to avoid overremovals by providing an immunity for removals “based on facts or circumstances from which the unlawful publishing of an intimate visual depiction is apparent.” Swell, but as Prof. Miers and I documented, services aren’t liable for content removals they make (subject to my point above about must-carry laws), whether it’s in response to heckler’s veto notices or otherwise. So the Take It Down immunity won’t motivate services to be more careful with their removal determinations because it does not provide any additional legal protection the services value.

The bottom line: however bad you think the DMCA encourages or enables overremovals, the Take It Down Act is 1000x worse due to its poor design.

One quirk: the DMCA expects services to do two things in response to a copyright takedown notice: (1) remove the targeted item, and (2) assign a strike to the uploader, and terminate the uploader’s account if the uploader has received too many strikes. (The statute doesn’t specify how many strikes is too many, and it’s an issue that is hotly litigated, especially in the IAP context). The Take It Down Act doesn’t have a concept of recidivism. In theory, a single uploader could upload a verboten item, the service could remove it in response to a takedown notice, the uploader could reupload the identical item, and the service could wait for another Take It Down notice before doing anything. In fact, the Take It Down Act seemingly permits this process to repeat infinitely (though the service might choose to terminate such rogue accounts voluntarily based on its own editorial standards). Will judges consider that infinite loop unacceptable and, after too many strikes (whenever that is), assume some kind of actionable scienter on services dealing with recidivists?

The FTC’s Enforcement Leverage

The Take It Down Act enables the FTC to bring enforcement actions for a service’s “failure to reasonably comply with the notice and takedown obligations.” There is no minimum quantity of failures; a single failure to honor a takedown notice might support the FTC’s action. This gives the FTC extraordinary leverage over services. The FTC has unlimited flexibility to exercise its prosecutorial discretion, and services will be vulnerable if they’ve made a single mistake (which every service will inevitably do). The FTC can use this leverage to get services to do pretty much whatever the FTC wants–to avoid a distracting, resource-intensive, and legally risky investigation. I anticipate the FTC will receive a steady stream of complaints from people who sent takedown notices that weren’t honored (especially the zealous anti-porn advocates), and each of those complaints to the FTC could trigger a massive headache for the targeted services.

The fact that the FTC has turned into a partisan enforcement agency makes this discretionary power even more risky to the Internet’s integrity. For example, imagine that the FTC wants to do an anti-porn initiative; the Take It Down Act gives the FTC a cudgel to ensure that services are overremoving pornography in response to takedown notices–or perhaps even to anticipatorily reduce the availability of “adult” content on their service to avoid potential future entanglements. Even if the FTC doesn’t lean into an anti-porn crackdown, Chairman Ferguson has repeatedly indicated that he thinks he works for President Trump, not for the American people who pay his salary, and is on standby to use the weapons at the FTC’s disposal to do the president’s bidding.

As I noted in my pieces on editorial transparency (1, 2), the FTC’s investigatory powers can take the agency deep into a service’s “editorial” operations. The FTC can investigate if a service’s statutorily required reporting mechanism is properly operating; the FTC can ask to see all of the Take It Down notices submitted to the service and their disposition; the FTC can ask why each and every takedown notice refusal was made and question if that was a “correct” choice; the FTC can ask the service about its efforts to find identical copies that should have been taken down and argue that any missed copies were not reasonable. In other words, the FTC now becomes an omnipresent force in every service’s editorial decisions related to adult content–a newsroom partner that no service wants. These kinds of close dialogues between editorial publishers and government censors are common in repressive and authoritarian regimes, and the Take It Down Act reinforces that we are one of them.

The Death of Due Process

Our country is experiencing a broad-based retrenchment in support for procedures that follow due process. I mean, our government is literally disappearing people without due process and arguing that it has every right to do so–and a nontrivial number of Americans are cheering this on. President Trump even protested that he couldn’t depopulate the country of immigrants he doesn’t like and comply with due process because it would take too long and cost too much.

Yes, due process is slow and expensive, but countries that care about the rule of law require it anyway because it reduces errors that can be pernicious/life-changing and provides mechanisms to correct any errors. Because of the powers in the hands of government and the inevitability that governments make mistakes, we need more due process, not less.

The Take It Down Act is another corner-cut on due process. Rather than requiring people to take their complaints about intimate visual depictions to court, which would take a lot of time and cost a lot of money, the Take It Down Act contemplates a removal system that bears no resemblance to due process. As I discussed, the Take It Down Act massively puts the thumb on the scale of removing content (legitimate or not) in response to heckler’s vetoes, ensuring many erroneous removals, with no meaningful mechanism to correct those errors.

It’s like the old adage in technology development circles (sometimes called the “Iron Triangle”): you can’t have good, fast, and cheap outcomes, at best you can pick two attributes of the three. By passing the Take It Down Act, Congress picked fast and cheap decisions and sacrificed accuracy. When the act’s takedown systems go into effect, we’ll find out how much that choice cost us.

Can Compelled Takedowns Survive a Court Challenge?

I’d be interested in your thoughts about whether the takedown notice procedures (separate from the criminal provisions) violate the First Amendment and Section 230. On the surface, it seems like the takedown requirements conflict with the First Amendment. The Take It Down Act requires the removal of content that isn’t obscene or CSAM, and government regulation of non-obscene/non-CSAM content raises First Amendment problems because it overrides the service’s editorial discretion. The facts that the censorship is structured as a notice-and-takedown procedure rather than a categorical ban, and the FTC can enforce violations per its unfair/deceptive authority, strike me as immaterial to the First Amendment analysis.

(Note: I could make a similar argument about the DMCA’s takedown requirements, which routinely lead to the removal of non-infringing and Constitutionally protected material, but copyright infringement gets a weird free pass from Constitutional scrutiny).

Also, Take It Down’s takedown procedures obviously conflict with Section 230 by imposing liability for continuing to publish third-party content. However, I’m not sure if Take It Down’s status as a later-passed law means that it implicitly amends Section 230. Furthermore, by anchoring enforcement in the FTC Act, the law may take advantage of cases like FTC v. LeadClick which basically said that the FTC Act punishes defendants for their first-party actions, not for third-party content (though that seems like an objectively unreasonable interpretation in this context). So I’m unsure how the Take It Down/Section 230 conflict will be resolved.

Note that it’s unclear who will challenge the Take It Down Act prospectively. It seems like all of the major services will do whatever they can to avoid triggering a Trump brain fart, which sidelines them from prospective challenges to the law. So we may not get more answers about the permissibility of the Take It Down Act scheme for years, until there’s an enforcement action against a service with enough money and motivation to fight.

Coverage

- The Verge: The Take It Down Act isn’t a law, it’s a weapon

- Reason: The TAKE IT DOWN Act’s Good Intentions Don’t Make Up for Its Bad Policy

- EFF: Congress Passes TAKE IT DOWN Act Despite Major Flaws

- Internet Society’s Letter on behalf of civil society organization, cybersecurity experts, and academics

- CDT’s Letter on behalf of technology policy organizations

- TechFreedom’s Tech Policy Podcast: The Take It Down Act (Is a Weapon)

- Techdirt: Congress Moving Forward On Unconstitutional Take It Down Act

- Ashkhen Kazaryan and Ashley Haek: The Road to Enforcement Chaos: The Hidden Dangers of the TAKE IT DOWN Act