Courts’ Expectations for TOS Formation Keep Going Up—Lee v. Plex

This is a VPPA claim against Plex (a video streaming service) regarding the use of Meta Pixels. 🙄🙄 The defendant invoked the arbitration clause in its TOS. Extensively citing Chabolla, the court rejects the arbitration request.

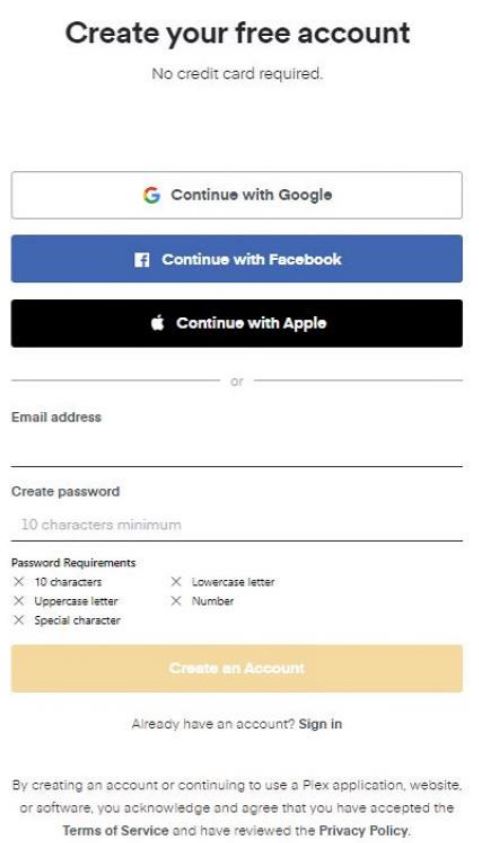

Here is Plex’s sign-up screen:

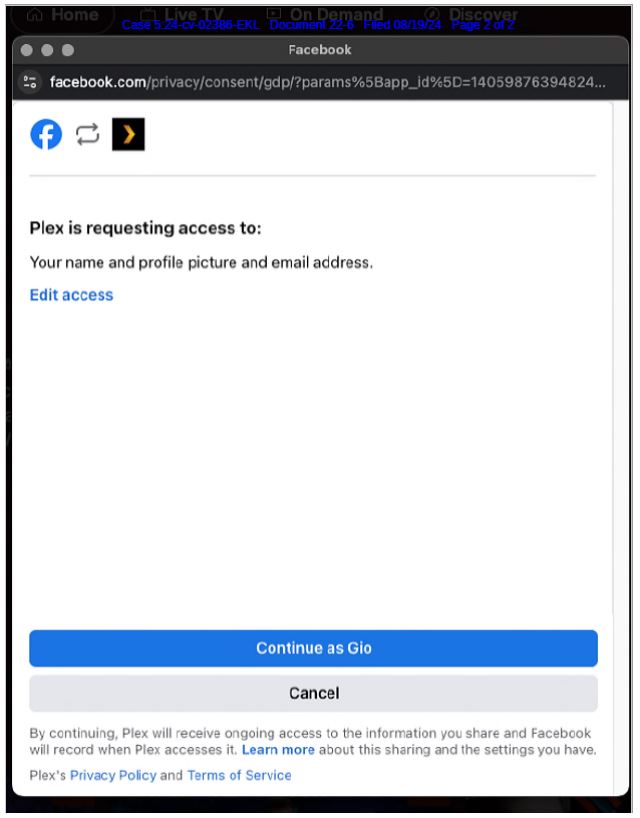

Instead of creating a native Plex account, the user in question clicked on the “Continue with Facebook” link, which put the user into the “Facebook Userflow” that included this screen:

The court classifies these screens as “sign-in-wraps” and proceeds to look for the standard elements of reasonably conspicuous notice of the TOS and manifestation of assent.

The court says Plex’s relationship context cuts against TOS formation. Plex offers free video streaming. The court says that that kind of relationship doesn’t impel viewers to assume they are forming an ongoing relationship that would require a TOS, because they can stop watching the free video content any time they want.

The court also says the disclosures were not reasonably conspicuous:

First, the notice was placed at the very bottom of the visible page, far below the “Continue with Facebook” button that Plaintiff clicked to create his account. Plaintiff had no reason to read to the bottom of the Sign-Up Page because clicking on the prominent “Continue with Facebook” button “automatically” directed him to the Facebook Userflow, where he completed the account creation process. Second, the notice is presented in small gray font at the bottom of the Sign-Up Page. Although it is legible, it is far less prominent than the colorful buttons that the user must click to create an account. Finally, the “Terms of Use” and “Privacy Policy” “appeared in the same gray font as the rest of the sentence, rather than in blue, the color typically used to signify the presence of a hyperlink.” The text is bolded, but it is not underlined or presented in a “contrasting font color” to indicate that it hyperlinks to additional terms. To the contrary, the same bolded gray font is also used for other elements of the Sign-Up Page that do not appear to be hyperlinks – namely, the text that states “Email address” and “Create password.”…

The Facebook Userflow also fails to provide reasonably conspicuous notice, though it fares better than the Sign-Up Page. Again, the links to the “Terms of Use” and “Privacy Policy” are located at the bottom of the page. They are closer to the blue “Continue” button that the user must click to create an account, but they do not “disrupt[ ] the natural flow of actions” on the page. The top of the Facebook Userflow informs the user that Plex is requesting access to the user’s profile picture and email address. The user can read this information and “Edit access” or click “Continue” without encountering the “Terms of Use” or “Privacy Policy.” Additionally, the “Terms of Use” and “Privacy Policy” text appears in the smallest font of any text on the page, and it is much less prominent than the interactive elements of the page – the “Continue” and “Cancel” buttons.

The lack of reasonably conspicuous notice would be enough to doom TOS formation. To reinforce Plex’s failings, the court says the consumers also don’t unambiguously manifest assent on these screens:

Plex argues that a user assents to its terms on the Sign-Up Page by clicking the “Continue with Facebook” button, but nothing in the notice language says this. The notice language at the bottom of the Sign-Up Page states: “By creating an account or continuing to use a Plex application, website, or software, you acknowledge and agree that you have accepted the Terms of Service and Privacy Policy.” In context, this language is ambiguous because it describes two actions that constitute assent, but neither matches the “Continue with Facebook” button that Plaintiff clicked.

First, “creating an account” constitutes assent, but a reasonable user could assume this means clicking the prominent “Create an Account” button that appears directly above the notice language. Second, “continuing to use a Plex application, website, or software” constitutes assent, but the button Plaintiff clicked “automatically” directed him to the Facebook website. Plaintiff did not continue to a Plex application, website, or software.

The notice language on the Facebook Userflow also fails to indicate what action constitutes assent. The notice states: “By continuing, Plex will receive ongoing access to the information you share and Facebook will record when Plex accesses it.” The phrase “Plex’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Service” appears beneath this notice, but nothing connects these terms to any action that the user takes on the Facebook UserFlow.

The court’s treatment of the sign-up screen’s call-to-action is perplexing (no pun intended). The language says “continuing to use a Plex application” which the court says the user didn’t do because they continued to Facebook. The court misreads the call-to-action to say something it doesn’t say. Having said that, the court is holding Plex to a very high standard–essentially saying that the language in the call-to-action must precisely match the desired action (in this case, the “continue with Facebook” button).

In contrast, the lack of a call-to-action in the Facebook Userflows seems obviously fatal to its formation. This is a prime example of a case where providing alternative ways to create an account can undermine TOS formation, because each pathway must independently ensure proper TOS formation.

As with Chabolla, the fact that Plex failed independently on two different screens doesn’t change the answer: “the Court will not find that a contract was formed by combining independently insufficient elements of notice and assent across several webpages.”

The court’s approach here is consistent with the more modern trend of judges applying exacting standards to TOS formation. Indeed, this court disagrees with a prior Plex case that found the TOS formed, Miller v. Plex, Inc., No. 22-cv-05015-SVK, ECF No. 32 (March 30, 2023). The court says that Chabolla occurred since the Miller ruling, which justifies the different outcome. This confirms that TOS formation processes that previously passed muster, even recently, may no longer be tenable. This decision reinforces the likelihood that Chabolla was a major ruling about TOS formation.

Despite the bummer ruling for Plex, most websites should have no problem meeting the heightened TOS formation standards if they try just a little harder. As the court summarized:

as a website operator, Plex controls its own destiny. Plex could have employed several common website design elements to make its sign-in wrap agreement more enforceable. The notice could be placed immediately above or beneath action items; the hyperlinks could be more clearly emphasized; and the language explaining the consequences of creating a Plex account could be clearer.

In a footnote, the court adds: “Although not required under Ninth Circuit law, using a clickwrap agreement would provide a website operator with greater assurance that the agreement will be enforced.” My view: skip that second click, and you get what you get.

Proper TOS formation really doesn’t seem that hard. Yet, the ongoing TOS formation futility we’re seeing in court suggests it’s harder than it seems.

Case Citation: Lee v. Plex, Inc., 2025 WL 948118 (N.D. Cal. March 28, 2025)

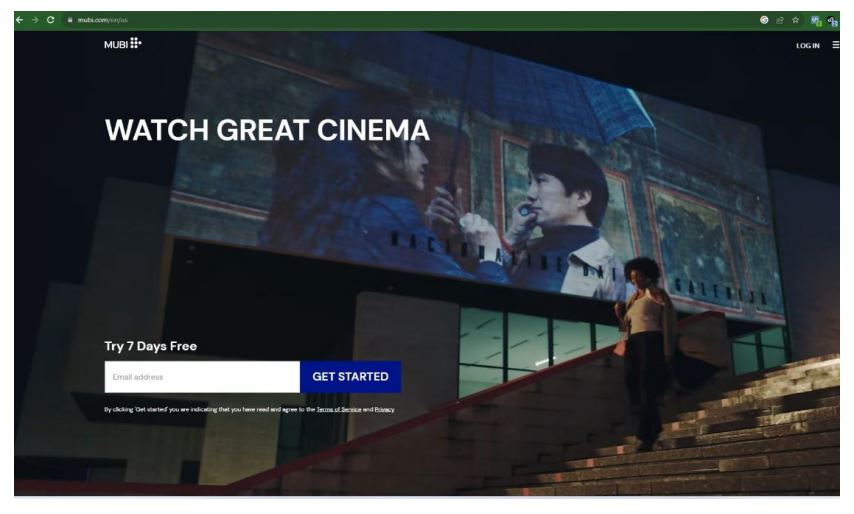

BONUS: Edwards v. Mubi, Inc., 2025 WL 985130 (N.D. Cal. March 31, 2025). Also a VPPA Meta Pixels case, also against a video streaming service, also in front of the same judge as the Plex case. Mubi argued that consumers consented to its Pixels disclosure via its privacy policy, which sets up the same contract formation issues as the Plex case. As with Plex, the court says that Mubi used a sign-in-wrap; and as with Plex, it doesn’t go well:

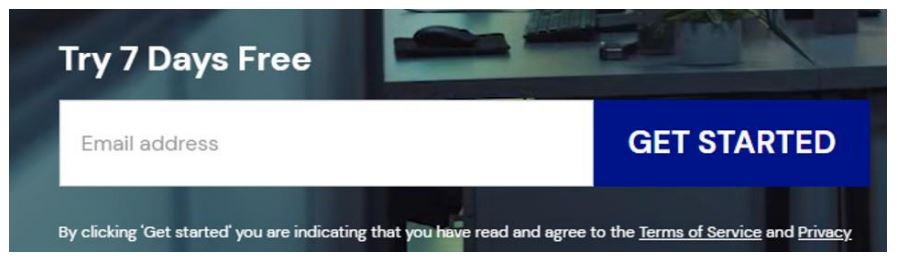

The Court finds that the notice on the Home Page is not reasonably conspicuous for three reasons. First, the notice on the main part of the Home Page is in tiny white font, below two prominent boxes that invite users to enter an email address and click “GET STARTED.” The underlined phrases “Terms of Service” and “Privacy” are hyperlinks, but they appear in the same tiny white font “as the rest of the sentence, rather than in blue, the color typically used to signify the presence of a hyperlink.” Second, the notice is set against a dynamic background of rolling movie clips that change over time and distract the user’s attention… Third, although the Home Page provides a second notice lower down that is set against a static white background and contains traditional blue hyperlinks, and is therefore more conspicuous, it still suffers from two deficiencies: the notice is in very small font, and it appears that the user must scroll down a significant distance from the first part of the Home Page. Users would have no reason to do so, since clicking on the prominent “GET STARTED” button at the top would automatically direct them to the page where they can start the trial.

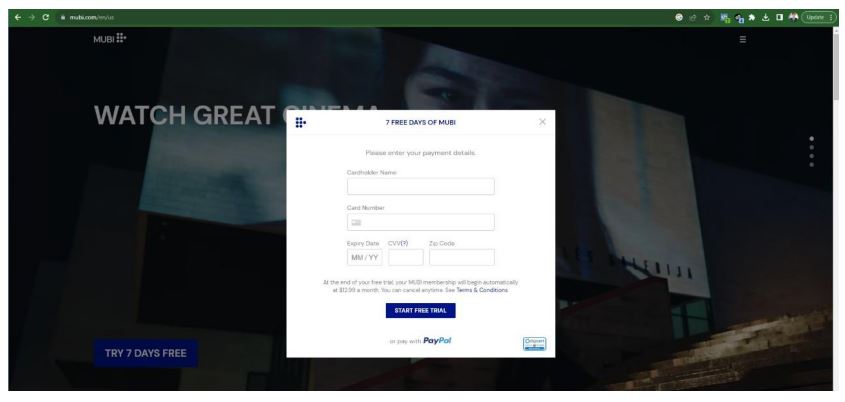

The Payment Page also fails to provide reasonably conspicuous notice. There, the notice states, “At the end of your free trial, your MUBI membership will begin automatically at $12.99 a month. You can cancel anytime. See Terms & Conditions.” “Terms & Conditions” is in blue font, indicating it is hyperlinked to MUBI’s terms, but there is no language indicating that the terms in question relate to MUBI’s PII disclosure policy, which is “buried several pages deep” in the Privacy Policy.

Home page:

You need a microscope to read the call-to-action. In fact, the court added a second shot with the call-to-action blown up. If the court needs to do this, you probably aren’t getting TOS formation. The blow-up:

Payment page: