Fourth Circuit Upholds TOS Formation Despite a Bad Call-to-Action, But Strikes Down Unilateral Amendment Clauses

Two noteworthy rulings this week from the Fourth Circuit regarding TOS formation issues.

Dhruva v. CuriosityStream, Inc., No. 24-1080 (4th Cir. March 10, 2025)

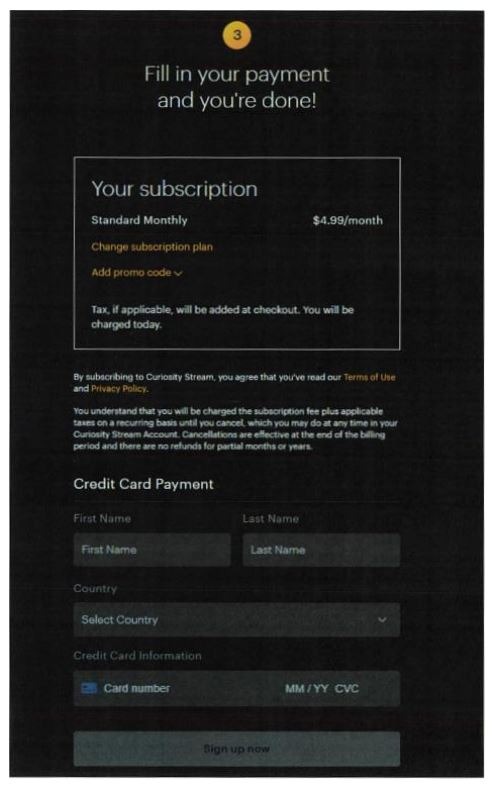

Curiosity Stream is a paywalled site for documentary videos. The plaintiffs brought a Meta pixels case against Curiosity Stream alleging VPPA and other claims. At issue is the following checkout screen which, if effective at forming the TOS, should send the case to arbitration:

The call-to-action is pretty hard to see (never a good sign). It says “By subscribing to Curiosity Stream, you agree that you’ve read our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.” The words “Terms of Use” and “Privacy Policy” are in an offsetting font color (orange on a black background) but not underlined. The court doesn’t use the -wrap terminology at all (YAY!). If it did, this would be a sign-in-wrap.

There are many suboptimal aspects of this TOS formation screen, but the plaintiffs focus on the deficient call-to-action. The if/then statement never actually says that by doing X, the plaintiffs agree to the TOS. It only signals confirmation that the plaintiffs read the TOS, not agreed to it. Whoops.

Nevertheless, the majority upholds the TOS formation: “We conclude Dhruva and Stern had reasonable notice of the terms of CuriosityStream’s offer and that they objectively manifested their assent to those terms by registering with the website.”

The majority focuses on the realpolitik of the situation. The plaintiffs procured a subscription, and a “subscription is, by definition, a contract.” Because the plaintiffs knew they were entering into some type of contract, the majority says “a reasonably prudent internet user would have known that the hyperlinked terms of use here applied to the subscription being finalized on the same page.”

The majority is not bothered by the bad grammar in the call-to-action (agreeing that the TOS was read, not agreeing to the TOS), saying that clear and conspicuous display of a TOS provides sufficient notice of the terms. This is bolstered by the TOS terms themselves, which self-servingly indicate that registering an account assents to the terms. In other words, because the plaintiffs agree that they read the terms, and the terms say that registration = assent, then the court uses formalist logic to say that the call-to-action is sufficient. Thus, in response to the plaintiffs’ objections to the bad purchase page call-to-action, the majority says the binding call-to-action was actually buried in the TOS and is not the call-to-action on the purchase page. 🙄

Let me be clear: Curiosity Stream got a hugely favorable roll of the dice here. If you actually care about forming your TOS, DO NOT DO WHAT CURIOSITY STREAM DID. I would not gamble that any similar implementation would get an equally favorable roll in the future.

Judge Wilkinson dissents due to the bad call-to-action grammar. He says the majority’s “judicial guesswork is no substitute for ‘clear and conspicuous’ notice.” He adds:

it is not clear [consumers] would have understood that the hyperlinked “Terms of Use” contained one. Internet users are regularly bombarded with pages labeled “Terms of Use,” “Terms of Service,” “Terms and Conditions,” “Privacy Policy,” and the like. Sometimes these pages present a contract offer; other times they contain disclosures, legal notices, or mere statements of policy…

A “Privacy Policy” is ordinarily a noncontractual document providing notice of how a company intends to use a customer’s data. By lumping the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy together, CuriosityStream invited reasonable consumers to assume that both documents were merely informational.

I don’t agree with this last part. Privacy policies are legally binding documents, either as marketing representations or bilateral contracts. Courts should not assume that a privacy policy was meant to be purely informational.

The dissent predicts lots of litigation over bad calls-to-action:

Courts will now be forced to parse through every turn of phrase to determine whether it comes close enough to “agree.” This decision invites litigiousness and leaves courts thrashing over a threshold issue, with the merits of the dispute still on the far horizon

To be fair, this litigation deluge is happening already. But not to readers of this blog, who already know they need to button up their calls-to-action so that there is no subtlety or ambiguity about the if/then statement. Indeed, the dissent highlights CuriosityStream’s dubious drafting choices:

Stating up front the presence of the arbitration clause as a term of the agreement would seem to be unimpeachable. Boldface would help. Simply making clear at the very outset that “by subscribing to Curiosity Stream, you agree to our Terms of Use” would be much better than what we have here. Is that so very hard?…

I am sympathetic to the result reached by my friends in the majority, but I do not agree with the means that CuriosityStream chose to get there. Means matter in the law and they were lacking here.

To answer the dissent’s question: No, it’s not hard, yet it’s apparently still too hard for far too many services.

* * *

Johnson v. Continental Finance Company, No. 23-2047 (4th Cir. March 11, 2025)

Note: this time, Judge Wilkinson is in the majority.

Continental issues credit cards. Its cardholder agreement has a “change-in-terms” clause allowing Continental to “change any term of [the credit card] Agreement” at its “sole discretion, upon such notice . . . required by law.” The provision is clearly intended to allow Continental to change its prevailing interest rate or other credit terms, but its application to other terms is open-ended.

The majority says: “Maryland courts have found this kind of clause to be so one-sided and vague that it allows a party to escape all of its contractual obligations at will…the language of the change-in-terms clause plainly applies to ‘any term of [the] Agreement,’ including the arbitration clause….[It] places no constraint on Continental’s ability to escape its contractual obligations whenever it sees fit.”

The fact that Continental committed to providing notice to consumers doesn’t save the provision. In contrast, the majority says that (riffing on a precedent) an amendment clause that could be exercised only 1x/year was not illusory because the vendor was committed the rest of the year. Also, the court notes that the notice doesn’t have to be ex ante.

Thus, the “plain language of the clause merely commits Continental to do what it is already required to do by law. That cannot furnish consideration….[The] sweeping grant of unilateral authority leaves no room for an interpretation that imposes any kind of limitation on Continental.”

The majority summarizes: “the change-in-terms clause here is so one-sided and so nebulous that it deprives the agreement of the kind of minimum reciprocity needed to form a contract under Maryland law.” Thus, all of Continental’s TOS goes into the trash.

Judge Niemeyer dissents regarding the change-in-terms clause’s enforceability: “any potential modification by Continental Finance could become binding on the plaintiffs only so long as Continental Finance gave notice of the modification to the plaintiffs and the plaintiffs assented to it by continuing to use their credit cards.”

To him, continued card use constitutes assent, which (a) gives unlimited power to the card issuer, and (b) elides the possibility that the cardholder cannot freely exit the arrangement in response to the changed terms.

The dissent concludes:

the majority’s holding…undermines the universal practice of allowing credit card companies to make changes so long as they provide credit card holders with notice and the opportunity to accept or reject the changes by either continuing to use the credit card or withdrawing from the arrangement

So…the big question…what should Continental have done differently? Obviously, bilateral assent would have sidestepped this problem, and the majority implies that a time restriction on the amendment process would provide some consideration (but that may be a nuisance for other reasons). Perhaps this ruling is a quirk of Maryland law–though it’s concordant with the uncited Harris v. Blockbuster Texas ruling from 15+ years ago.

Would any options short of mutual assent that would have satisfied the majority? In my Internet Law course, I cover the following options for getting consumer consent to TOS amendments:

- Not consent: posting without notice

- Consent: mandatory clickthrough

- Consent (probably): form parallel contracts

- Take your chances: provide notice & opt-out

I think this ruling emphasizes the latter bullet point. An amendment imposed by notice and opt-out (in this case, by terminating the contract) sometimes works, sometimes doesn’t. Here, Continental took its chances and it didn’t work.

I’d welcome your thoughts about how this Continental ruling changes your thinking about the TOS amendment implementation strategies.