Court Upholds Google’s Ad TOS Amendment to Add an Arbitration Clause–In re Google Digital Advertising Antitrust Litigation

This is a long-running litigation battle over Google’s advertising practices. In 2021, many individual advertiser claims were consolidated into an MDL in SDNY. Four years and 900+ docket entries later, the SNDY court holds that two plaintiffs’ claims must go to arbitration. Because other advertisers probably have similar facts, I assume much of this litigation is headed to arbitration unless the appeals court intervenes.

At issue is Google’s September 2017 amendment of its Advertising TOS to add an arbitration clause. The court describes the steps Google took to effectuate the amendment:

Google launched a notice campaign that included a direct email to advertisers, a public blog post, and an alert presented to advertisers when they logged into their accounts. These notices included a link that, when clicked, took advertisers to a webpage containing the September 2017 Terms

The court doesn’t distinguish between these various notification modalities, but the one that stands out is the interstitial alert. The court doesn’t provide a screenshot of that display, but it suggests that the advertisers actually saw the notice. As we’ve seen in other cases, email notification alone may not be airtight. The public blog post is likely irrelevant to the amendment process.

The court also doesn’t provide the text of the notice campaign (I can’t tell if Google produced it?). It’s a weird omission because the text has significant bearing on whether advertisers were likely to click on the link to the new terms.

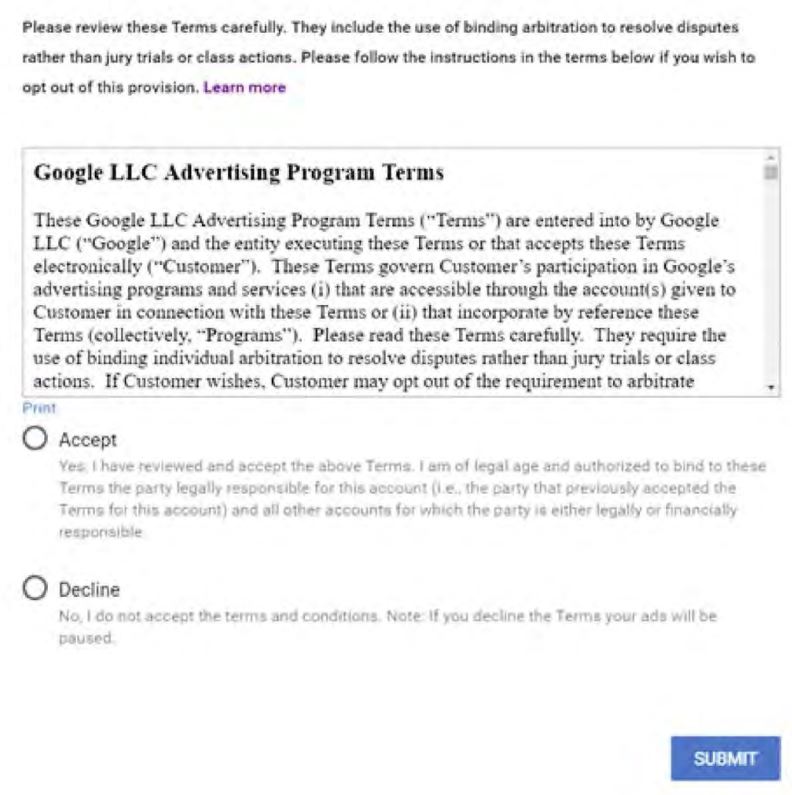

If advertisers did click to see the new terms page, Google prominently announced the addition of the arbitration clause and the opportunity to opt-out. Here’s a screenshot of this screen:

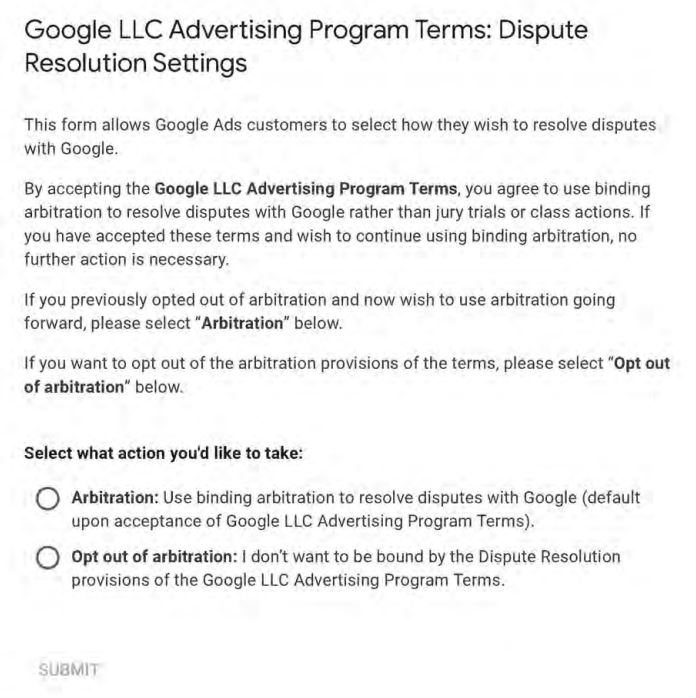

The TOS text included a provision allowing advertisers to opt-out of arbitration within 30 days. Unlike some opt-out options that require onerous efforts, Google provided a link to a web form where advertisers could click to say no. But because this opt-out and URL were buried in the TOS, this option was not exactly prominent beyond the earlier shoutout. Here’s the web form:

With respect to the advertisers in question:

Google’s records reflect that plaintiff Stellman accepted the Terms on September 14, 2017, and that Cliffy Care later accepted the Terms on November 20, 2019, when it first signed up for an advertising account with Google. Google records identify whether an advertiser has opted out of arbitration, and records for Cliffy Care and Stellman reflect that they did not.

Based on these facts, the court treats the amendment as presumptively enforceable.

Stellman argued that the court needed to see the text of the notice campaign to confirm that it actually displayed a link to the terms. The court responds: “Given that Stellman accepted the Terms, the contents the alerts [sic] in Google’s notice campaign are of little moment to the existence of the agreement.”

Cliffy Care challenged the exact TOS terms it agreed to when it created a new account. Google’s records show that Cliffy Care agreed to “agreement 294, version 2.5, legal_document_id 131839,” but Cliffy Care says this may not be the same as the TOS text Google submitted in its filings. The court says this objection is too speculative to cast doubt on Google’s evidenece.

The advertisers’ unconscionability arguments don’t persuade the judge either. The court points to their ability to opt-out of arbitration and says “neither Stellman nor Cliffy Care claims to have been actually confused by the Terms, blindsided by the inclusion of the arbitration clause, or state that they were pressured or coerced into accepting the arbitration provision.”

Implications

The court denied Google’s requested arbitration in March 2024, but grants it now. What’s the difference? In the interim, Google and advertisers conducted fact discovery on the TOS formation/amendment. Thus, Google’s earlier request was based on less definitive facts than the successful request (it’s a bit like the distinction between a motion to dismiss and summary judgment). After the fact discovery, the court was able to confidently state the facts without just relying on Google’s self-representations. That turned a preliminary Google loss into a relatively easy Google win.

At the core of Google’s success was its evidentiary recordkeeping, which meant it could definitively point to when the advertisers agreed to the terms in a manner that convinced the judge. A different way of saying this: you can have the most airtight contract formation process ever, but if you can’t provide credible evidence of the process, it can still fail in court. Pay attention to your recordkeeping and evidence management when implementing and amending TOSes.

Still, while Google’s evidence management deserves some praise, I’m still scratching my head about why the court didn’t display the text of the notice campaign.

Case Citation: In re Google Digital Advertising Antitrust Litigation, 2025 WL 289726 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 25, 2025). The CourtListener page.