Comments on the Free Speech Coalition v. Paxton SCOTUS Oral Arguments on Mandatory Online Age “Verification”

Today, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Free Speech Coalition v. Paxton, regarding a Texas law that requires adult-oriented websites to age-authenticate all users–minors and adults alike–before they can enter their “virtual” premises. If this sounds familiar, that’s because Texas’ law is virtually identical to two laws enacted by Congress in the 1990s (the Communications Decency Act and Child Online Protection Act), both of which the Supreme Court struck down over 2 decades ago. Texas’ legislative approach wasn’t clever or subtle. Instead, Texas said, let’s pass a virtually identical law and hope the Supreme Court will reach a different answer now. Texas made that sale (not surprisingly) at the Fifth Circuit, which bypassed more directly-on-point precedent to reach back to a 55-year-old precedent that applied the most relaxed level of constitutional scrutiny and allowed the law to go into effect.

Today, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Free Speech Coalition v. Paxton, regarding a Texas law that requires adult-oriented websites to age-authenticate all users–minors and adults alike–before they can enter their “virtual” premises. If this sounds familiar, that’s because Texas’ law is virtually identical to two laws enacted by Congress in the 1990s (the Communications Decency Act and Child Online Protection Act), both of which the Supreme Court struck down over 2 decades ago. Texas’ legislative approach wasn’t clever or subtle. Instead, Texas said, let’s pass a virtually identical law and hope the Supreme Court will reach a different answer now. Texas made that sale (not surprisingly) at the Fifth Circuit, which bypassed more directly-on-point precedent to reach back to a 55-year-old precedent that applied the most relaxed level of constitutional scrutiny and allowed the law to go into effect.

My view is that the Supreme Court isn’t likely to take Texas’ bait and will not agree with the Fifth Circuit’s apathetic level of constitutional review. Oral arguments are always a little tricky to predict, but I heard at least five votes (Barrett, Jackson, Kagan, Kavanaugh, Sotomayor) to reverse the Fifth Circuit’s opinion allowing the law to go into effect. (Roberts is a wild card, and the other three justices usually vote against what’s best for the Internet). The details of the court’s opinions will matter a lot, but this oral argument was not a win for the Fifth Circuit’s decision.

The justices had a mind-bending discussion about what happens after the Supreme Court reverses in this case. You would think that after 2+ centuries of Supreme Court practice, those consequences would be clear, but no. If the Supreme Court reverses the Fifth Circuit, will the district court’s injunction go back into effect, or does the law remain in effect while the Fifth Circuit does more work? Surprisingly, the justices weren’t sure.

There was a lot of discussion about how online age authentication differs from offline age authentication. I filed an amicus brief on this very point because it’s critical to the discussion and there are major and legally significant factual differences, including:

There was a lot of discussion about how online age authentication differs from offline age authentication. I filed an amicus brief on this very point because it’s critical to the discussion and there are major and legally significant factual differences, including:

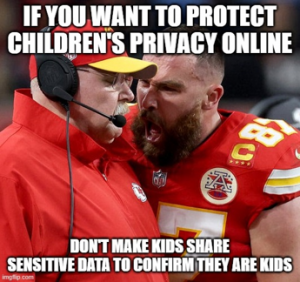

- Greater privacy risks. Compared to offline, online age authentication requires minors and adults to make more disclosures of private and sensitive information and put themselves at greater risk.

- Greater security risks. Because of the online mediation, the highly sensitive online authentication information is more susceptible to theft or exfiltration, posing huge dangers to the exposed data subjects.

- Greater barriers to access. Compared to offline, online age authentication adds a mandatory speed bump to content access online in ways that break ordinary Internet browsing and deter people from accessing constitutionally protected material.

- Greater publication costs. Compared to offline, online age authentication raises publishers’ costs that will shrink the availability of constitutionally protected material for minors and adults.

- Surveillance infrastructure. Compared to offline, mandatory online age authentication provides governments with much greater control over people’s movements online. Worse, it teaches citizens–especially minors–that the standard price of reading constitutionally protected material is the forced disclosure of highly sensitive and personal information. As that message becomes normalized, it will become easier for the government to degrade civil liberties in the future.

For these and other reasons, I take the position that mandatory online age authentication is (a) terrible policy, and (b) never constitutional. If we can agree on the second point (which the justices weren’t ready to do), we can shift our efforts to more productive conversations about a wider range of solutions that have better odds of keeping children safer online. Those solutions have to be a whole-of-society approach, not just putting all of the safety burden on online publishers.

(I will expand on all of these points in my Segregate-and-Suppress article, coming soon).