Another Court Finds an “Enforceable Browsewrap.” MAKE IT STOP–Hawkins v. CMG

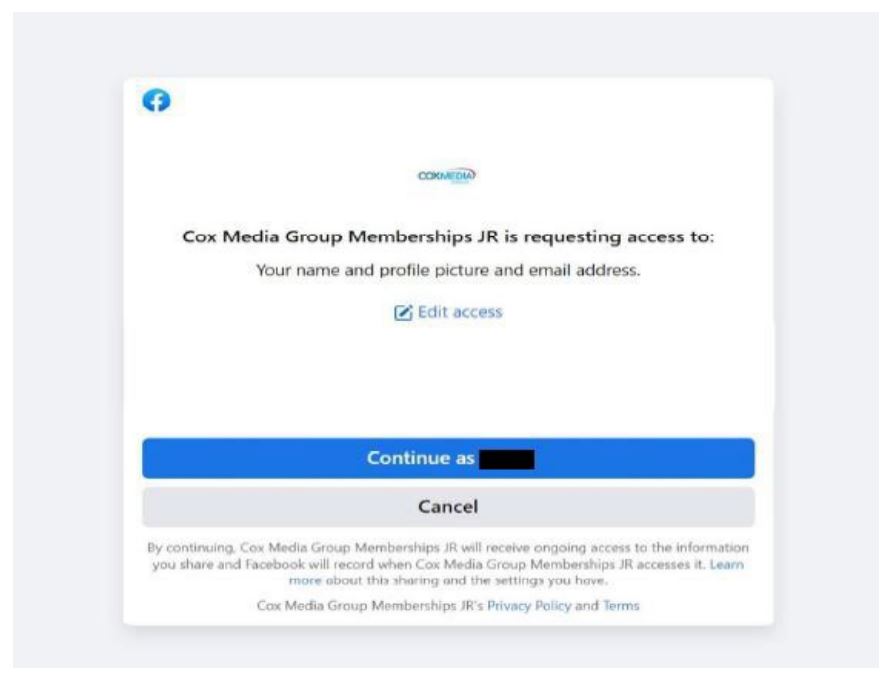

This is a Video Privacy Protection Act (VPPA) case against a media website, so you have good reason to wonder about the legitimacy and sincerity of the case. The named plaintiff created a WSBTV account by opting to log in using Facebook. That choice led the plaintiff to this screen:

If plaintiff had clicked on the “Terms” link at the bottom right, it would have led to CMG’s “Visitor Agreement” that included an arbitration clause. CMG is invoking arbitration based on that clause.

The court says this implementation isn’t a sign-in-wrap because the CMG terms lacked a call-to-action: “the login through Facebook screen never informed Plaintiff that acceptance of a separate agreement was required before she could access the service, which is the defining feature of a sign-in wrap agreement.”

So far so good, but then the court evaluates if this implementation is an enforceable browsewrap. Spoiler: the court says it is. UGH. How does this court reach this dubious conclusion?

The court says the web page is relatively uncluttered, so “it is highly likely that a reasonable user would see the ‘Terms’ hyperlink”:

- “the hyperlink is not tucked away…the relevant hyperlink is placed directly below the sentence that explains what happens when a user elects to continue registering for a WSBTV.com account”

- “the relevant hyperlink remains close to the button that a user must select to continue or cancel”

- “the hyperlink appears to be in the same size font—not a smaller font—and is set off in a different color than the surrounding text”

I think the visibility of the “terms” link is just OK, but the missing call-to-action seems like a big problem. The court seems to be bothered by that too: “courts should also consider whether the website contained an explicit textual notice that continued use of the website acts as a manifestation of the user’s intent to be bound by an agreement.” Nevertheless, without a call-to-action, the court says that the users were on inquiry notice because (1) “to complete the registration of the account, a user must press a continue button”; and (2) “a reasonable user would know that there was some legal significance attached to the continue button.” Thus:

Immediately following the invitation to learn more is a plainly clickable hyperlink to the “Terms.” By requiring a user to press the continue button and by explaining the legal significance of clicking on the continue button, the Court is unpersuaded by Plaintiff’s argument that she had no way of knowing that continuing would bind her to terms and conditions. Rather, the Court finds that a reasonable person would understand that by agreeing to continue, she would be bound by the information sharing provisions and the additional “Terms” contained in the hyperlink.

This is clearly wrong, no? The court says that users would know there is some legal significance to the button, yet the text on the page explicitly enumerates the legal significance of proceeding (the privacy consequences). The court seems to be saying that, in addition to those expressly described consequences, a reasonable person would assume that there were binding legal consequences available at the “terms” link (and presumably the “privacy policy” link) that were also part of the decision to proceed, even though CMG did nothing to encourage that assumption or make it explicit. It would have been trivially easy for CMG to add the call-to-action. Their failure to do so puts an unreasonably large “inquiry” burden on reasonable people.

So this is how the court reaches the conclusion that a “browsewrap” is enforceable–by disregarding the “call-to-action” requirement by making dubious presumptions about consumer psychology. (I recognize that all online TOS formation cases have an undercurrent of fiction, but this layers too many fictions on each other). It’s a nice legal trick if a website can get a judge to adopt it. I wouldn’t expect many other judges to do so, and I wouldn’t be surprised if this ruling gets reversed on appeal.

This ruling is complementary to the Ninth Circuit’s Running Warehouse ruling, which also found an “enforceable browsewrap” (even though that implementation was clearly what I’d call a clickthrough, not a browsewrap). Courts: PLEASE PLEASE PLEASE retire the “wrap” terminology. It is NOT HELPFUL. And if you’re reaching the conclusion that a browsewrap is enforceable, you are almost certainly doing it wrong.

Putting aside the court’s wrap dalliance, this case provides a reminder about the legal perils of offering multiple account formation options, such as “log in with Facebook” option. Those options lower access barriers for users to create accounts, so they are often compelling to the marketing team. However, the legal team must ensure that all account creation options presented to users satisfy minimum TOS formation processes. My guess is that CMG’s legal team didn’t properly vet this Facebook login option for TOS formation procedures. That put their litigation team in the position of needing to make a hail-mary argument of “enforceable browsewrap.” Kudos to the litigation team for making the unlikely sale to the judge–but you should never leave such a crucial legal protection up to chance like that.

Case citation: Hawkins v. CMG Media Corp., 2024 WL 559591 (N.D. Ga. Feb. 12, 2024).