Court Says No Human Author, No Copyright (but Human Authorship of GenAI Outputs Remains Uncertain) (Guest Blog Post)

by guest blogger Heather Whitney

To the surprise of no one, a D.C. district court granted summary judgment for the Copyright Office in Thaler v. Perlmutter, No. 1:22-cv-01564 (D.D.C. Aug. 18, 2023), affirming the Copyright Office’s position that “a work generated entirely by an artificial system absent human involvement [is not] eligible for copyright.” U.S. copyright law protects only works of human authorship, and the defendant, Stephen Thaler, expressly told the Copyright Office that the work at issue, titled “A Recent Entrance to Paradise,” “lack[ed] traditional human authorship.” Eric previously blogged about the Copyright Review Board’s affirmance of the Office’s repeated refusal to register the work back in March 2022.

The Thaler decision is unlikely to have any great impact. There aren’t many people trying to register works “autonomously created by a computer algorithm running on a machine” and disclaiming any human authorship at the outset. The much harder question of “how much human input is necessary to qualify the user of an AI system as the ‘author’ of a generated work” was not before the court. That said, while not presented with the question of how much human input is enough, the court’s dicta arguably suggests that it thinks there is some amount of human input to a generative AI tool that would render the relevant human an author of the resulting output.

This post focuses on the district court’s reasoning. However, before getting to Thaler, it’s worth pausing to underscore the impact that the answer to this harder human-authorship-of-works-created-using-generative-AI question will have.

Take the software industry. Coding assistants like GitHub Copilot, which can auto-complete code, are used by a lot of developers to generate a lot of code. Microsoft’s CEO, Satya Nadella, said last month that 27,000 companies are paying for a GitHub Copilot enterprise license. Just think about how many engineers are using coding assistants without their employers paying for it (or knowing about it). As of February 2023, GitHub announced that, for developers using Copilot, Copilot is behind 46% of the “developers’” code across all programming languages and 61% of all code written in Java. Those percentages are only going to go up as these tools get better, and companies are currently competing to provide the go-to coding assistant tool that developers will use.

But if developers aren’t the “authors” of code they create using coding assistants (and they aren’t adding copyrightable expression to the assistant-generated code after the fact) and the bulk of a company’s proprietary code is generated by a coding assistant, that means the bulk of a company’s proprietary code is not protected by copyright. Regardless of one’s views on the extent to which copyright should protect code, that it might not protect the majority of code created moving forward is a big (and underappreciated) deal.

Thaler Decision: “Works of (Human) Authorship”

The Progress Clause of the Constitution gives Congress the power to “promote the Progress of Science . . . by securing for limited Times to Authors . . . the exclusive Right to their . . . Writings[.]” U.S. Const. art. I § 8, cl. 8. Pursuant to this authorization, the Copyright Act extends copyrights to “original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression.” 17 U.S.C. § 102(a). The Copyright Act neither defines “authorship” nor “works of authorship.” That said, something cannot be a work of authorship without being the work of at least one author, if for no other reason than the work must be “fixed” in a tangible medium of expression “by or under the authority of the author.” 17 U.S.C. § 101.

Reviewing the Copyright Office’s refusal to register the work under the APA’s arbitrary and capricious standard, the district court gave four main reasons why only humans can be authors, and thus why summary judgment for the Copyright Office was appropriate. (For the record, I’m confident the Copyright Office’s decision could have been reviewed de novo and the district court would have reached the same conclusion.)

1. Precedent.

Courts have never recognized copyright protection in works or elements of works that were not authored by humans. And, while Thaler could not point to a single case of a court recognizing copyright in a work “authored” by a non-human, there are a handful of cases where courts affirmatively refused to do so on the grounds that copyright only protects works of human authorship. As one example of this, the district court pointed to Urantia Found. v. Kristen Maaherra, 114 F.3d 955 (9th Cir. 1997). In Urantia, the Ninth Circuit found a collection of “revelations” purportedly authored by divine beings copyrightable, but only as a compilation. While the selection and arrangement of the “revelations” by humans met the “‘extremely low’ threshold level of creativity required for copyright protection,” the individual “revelations” themselves were not “original” to any human author and thus were not copyrightable.

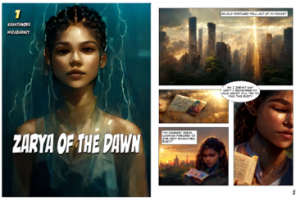

Some commentators have incorrectly taken Urantia to stand for the proposition that works by non-humans can be copyrightable. Again, the only copyrightable portion was the human’s selection and arrangement of non-protected elements. The Copyright Office made a similar move with respect to its treatment of Kristina Kashtanova’s (they/their) comic Zarya of the Dawn when it registered the work as a compilation but refused to find the images that Kashtanova made using Midjourney to be copyrightable. (My co-author and I discuss the Copyright Office’s decision here.) (Disclosure: I represent Kashtanova in connection with their application to register “Rose Engima.” You can read our cover letter here.)

Some commentators have incorrectly taken Urantia to stand for the proposition that works by non-humans can be copyrightable. Again, the only copyrightable portion was the human’s selection and arrangement of non-protected elements. The Copyright Office made a similar move with respect to its treatment of Kristina Kashtanova’s (they/their) comic Zarya of the Dawn when it registered the work as a compilation but refused to find the images that Kashtanova made using Midjourney to be copyrightable. (My co-author and I discuss the Copyright Office’s decision here.) (Disclosure: I represent Kashtanova in connection with their application to register “Rose Engima.” You can read our cover letter here.)

2. The District Court’s Reading of the Supreme Court.

While the Supreme Court has never squarely addressed the question of whether non-humans can be authors (many claims to the contrary notwithstanding), the district court found that “[h]uman involvement in, and ultimate creative control over, the work at issue was key to the [Supreme Court’s] conclusion that [photography] fell within the bounds of copyright” in Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, 111 U.S. 53 (1884). (Christa Laser discusses Sarony in her recent guest post, as have I and my co‑author here.) The district court also thought that the Supreme Court’s decisions in Mazer v. Stein, 347 U.S. 201 (1954) and Goldstein v. California, 412 U.S. 546 (1973) centered authorship on “acts of human creativity.”

While the district court’s account of why the Sarony court concluded that photographs are copyrightable was accurate, it highlights again how much lower the bar for photography is today. And, consequently, it hints at the brewing tension between the Copyright Office’s treatment of works that artists create using generative AI tools and the treatment of works that artists create using cameras (including camera phones).

As the district court put it:

In Sarony . . . the Supreme Court reasoned that photographs amounted to copyrightable creations of ‘authors’ . . . because the photographic result nonetheless ‘represent[ed]’ the ‘original intellectual conception of the author . . . A camera may generated only a ‘mechanical reproduction’ of a scene, but does so only after the photographer develops a ‘mental conception’ of the photograph, which is given its final form by the photographer’s decisions like ‘posing the [subject] in front of the camera, selecting and arranging the costume, draperies, and other various accessories in said photograph, arranging the subject . . . arranging and disposing the light and shade, suggesting and evoking the desired expression, and from such disposition, arrangement, or representation’ crafting the overall image. Human involvement in, and ultimate creative control over, the work at issue was key to the conclusion that the new type of work fell within the bounds of copyright.

I was not surprised to see the National Press Photographers Association and Professional Photographers of America as fellow speakers at the Copyright Office’s recent “listening session” on generative AI and copyright for visual works—precisely because the arguments that the Copyright Office made against Kashtanova being an author could quite easily be used to cast doubt on the copyrightability of the vast majority of photographs.

3. The Copyright Act’s “Plain” Language.

While acknowledging that the Copyright Act does not define “author,” the district court appears to cite modern definitions of “author” to support its conclusion that “[b]y its plain text, the [Copyright Act] requires a copyrightable work to have an originator with the capacity for intellectual, creative, or artistic labor.” The district court then simultaneously asserts that that “originator” must be human while also dropping a footnote that suggests the opposite. Specifically, citing Justin Hughes’ work, the court left open the possibility that non-human sentient beings may be covered, but dismissed this issue because “[t]he day sentient refugees from some intergalactic war arrive on Earth and are granted asylum in Iceland, copyright law will be the least of our problems.”

Some day in the future, as the technology continues to advance, there will be AIs that generate content that some people will believe to be sentient, and those people will latch on to this comment. Indeed, in the Hughes article that the court cites, Hughes sees something along these lines, noting that “once some AI is sentient enough to demand its own civil rights and protection under the Thirteenth Amendment, my guess is that ‘person’ in copyright law will not be limited to homo sapiens.” (For what it’s worth, an AI tool can say that it demands its own civil rights and protection under the Thirteenth Amendment today. It can also say that the year is actually 2000 and we are all living in a simulation.)

4. Purpose of Copyright Protection.

Referring to the Progress Clause, the district court notes that the purpose of copyright, which it characterizes at the promotion of the public good through incentivizing (human) individuals to create, are not furthered by extending copyright to works created without any human involvement. “Non‑human actors need no incentivization with the promise of exclusive rights under United States law, and copyright was therefore not designed to reach them.”

Concluding Thoughts

Again, not a surprising result. Nonetheless, Thaler’s lawyer has stated that they plan to appeal. Thaler’s appeal to the Federal Circuit and petition for certiorari in his analogous patent case were both unsuccessful.

No court has yet addressed whether (and if so, when) humans are the authors of content that they generate through the use of generative AI tools. I suspect that will change relatively soon. While most companies and creators have been focused on the infringement risks raised by the use of generative AI tools, few have thought through their own ability to protect IP they create using those tools moving forward. Defendants in future copyright infringement suits are bound to argue that the works at issue were made using generative AI tools and thus are not protected by copyright at all. It is hard to say at this stage when those defendants will be successful.

* * *

Eric’s Comments

The word “human” appears in the Thaler opinion 50 times. That’s because the court repeatedly says numerous times in different ways: no human creation = no copyright. That answers the question when human involvement in content creation is a binary switch–either on or off. Nowadays, humans routinely use machines to create content, and sometimes the machines contribute a lot to the final outcome. Trying to cleave the human part from the machine contributions sounds impossible, but that’s where the Copyright Office’s position is taking us.

I recently gave a short talk on copyright and generative AI. The video. The slides.

Pingback: Links for Week of August 25, 2023 – Cyberlaw Central()