U.S. Supreme Court Vindicates Photographer But Destabilizes Fair Use — Andy Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith (Guest Blog Post)

[Eric’s note: this is the post you’ve been waiting for: Prof. Ochoa’s definitive analysis of the Supreme Court’s Warhol opinion. This post is 11,000+ words long, so you may want to block out some time to enjoy this properly.]

By Guest Blogger Tyler Ochoa

By a 7-2 vote, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed the Second Circuit’s ruling that the reproduction of Andy Warhol’s Orange Prince on the cover of a magazine tribute was not a fair use of Lynn Goldsmith’s photo of the singer-songwriter Prince, on which the Warhol portrait was based. Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, No. 21-869 (May 18, 2023).

The majority opinion by Justice Sotomayor repeatedly emphasized that the ruling was narrow and context-specific. Despite those caveats, the opinion is likely to be enormously consequential, far more so than the Court’s similarly narrow and context-specific ruling two years ago in the Google v. Oracle software case. (See my commentary on that case here.) For nearly 30 years, the framework for judging fair use cases has been remarkably stable, based on Justice Souter’s masterful opinion for a unanimous Court in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569 (1994). The majority opinion in Warhol purports to follow the Campbell framework, but instead it reinterprets Campbell in ways that destabilize that three-decade consensus, likely resulting in a decade or more of renewed battle over the contours of the fair-use doctrine.

Many copyright scholars and most in the world of fine art have loudly condemned the ruling as a travesty of justice. Others, including many copyright owners and lawyers, and some scholars, have more quietly welcomed the ruling as a necessary corrective to a fair use doctrine they believe had tilted too far in the direction of copyright re-use. My own opinion is more nuanced and attempts to bridge the vast chasm between these two opposing views. I was not at all surprised that the Supreme Court ruled in Goldsmith’s favor, and I agree with the quiet mainstream that the Court reached a just and defensible result on the specific facts before it. Nonetheless, I also agree with the ruling’s critics that the opinion went much further than was necessary to reach that result, leaving the fair-use doctrine unmoored in stormy seas and even more susceptible to the whims and caprice of individual judges.

To fully understand these conflicting views of the majority opinion, it is necessary to understand both the specific facts of the case and the history of the Supreme Court’s case law concerning the fair-use doctrine. As usual, readers who are already familiar with the case and/or with copyright law may skip the “Background” sections below (but don’t skip the commentary “The Road Not Taken”).

Legal Background: Copyright and Derivative Works

Copyright law protects original works of authorship, including “pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works,” 17 U.S.C. §102(a)(5), a category that is defined to include photographs, 17 U.S.C. §101. For such works, copyright grants the author or artist who creates the work four of the five exclusive rights: the right to reproduce the copyrighted work (in whole or in part); the right to prepare derivative works based on the copyrighted work; the right to distribute copies (reproductions) of the copyrighted work; and the right to publicly display the copyrighted work. 17 U.S.C. §106. (For obvious reasons, the copyright in a photograph does not include the right to publicly perform the copyrighted work. Id.)

A “derivative work” is defined as a “a work based upon one or more preexisting works,” such as the movie version of a book, “or any other form in which a work may be recast, transformed, or adapted.” 17 U.S.C. §101. When a derivative work is prepared lawfully, the creator of the derivative is entitled to their own copyright, 17 U.S.C. §103(a); but importantly, the separate copyright in a derivative work “extends only to the material contributed by the author of such work, as distinguished from the preexisting material employed in the work.” 17 U.S.C. §103(b).

Thus, exploitation of a derivative work ordinarily requires the permission of both the owner of the copyright in the underlying work and the owner of the copyright in the derivative work. For example, when a sound recording of a musical work gets played on Spotify, both the owner of the copyright in the musical work and the owner of copyright in the sound recording (the derivative work) are entitled to royalties for the public performance. Similarly, when an artist lawfully creates a derivative work based on a photograph, and copies of that derivative work are reproduced and distributed to the public, ordinarily the owner of copyright in the photograph and the owner of copyright in the derivative work are entitled to royalties.

By contrast, when a derivative work is prepared unlawfully, the creator of the derivative work is entitled to no rights, and is merely an infringer. 17 U.S.C. §103(a) (“protection for a work employing preexisting material in which copyright subsists does not extend to any part of the work in which such material has been used unlawfully.”). Thus, if an artist creates a derivative work based on a photograph unlawfully, and copies of that derivative work are reproduced and distributed to the public, the owner of copyright in the photograph is entitled to sue for copyright infringement and to recover remedies for the unlawful use of their photograph.

The term “lawfully” is often used as a synonym for “with permission,” but the two terms are not the same. More precisely, the term “lawfully” includes, but is not limited to, derivative works created with permission of the copyright owner in the underlying work. Specifically, when a derivative work is created pursuant to a statutory exception, then the derivative work is prepared “lawfully,” even though the artist who created the derivative did not get a license or other permission from the owner of the copyright in the underlying work.

This has important implications for the doctrine of fair use. If the preparation of a derivative work is a fair use, then the artist who made the derivative work gets a copyright in the modifications that they made to the underlying work. But if the preparation of the derivative work is not a fair use, then the second author is merely an infringer, and has no legal rights.

Factual Background

(The facts are taken primarily from the Supreme Court’s opinion, with selected facts added from the District Court’s opinion.)

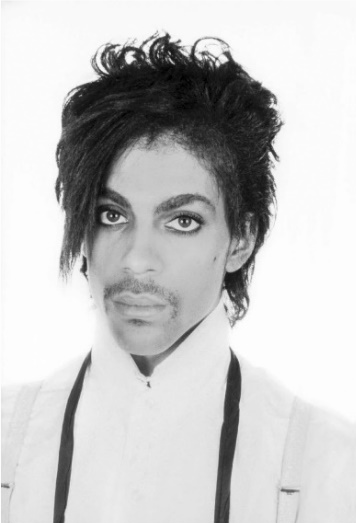

In December 1981, Lynn Goldsmith, a professional freelance photographer, took a number of photographs of Prince (then 23 years old) on assignment for Newsweek, both in concert and in her studio in New York. In October 1984, three months after the release of Prince’s hit movie and soundtrack album Purple Rain, Goldsmith’s photo agency (Lynn Goldsmith, Inc., or LGI) granted Condé Nast Publications a license to use one of her black-and-white photos of Prince as an “artist’s reference for an illustration … to be published in Vanity Fair November 1984 issue.” Condé Nast paid $400 for the license, which specified “No other usage right granted.” The license transaction was handled by the LGI’s staff; Goldsmith herself was not even aware of the license or the subsequent use.

[Figure 1, Slip op. at 4]

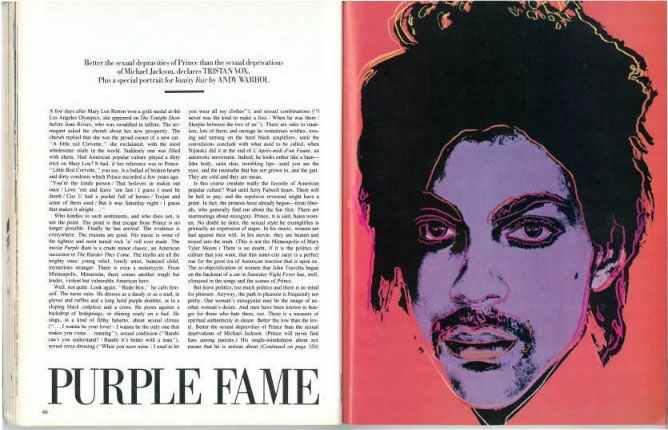

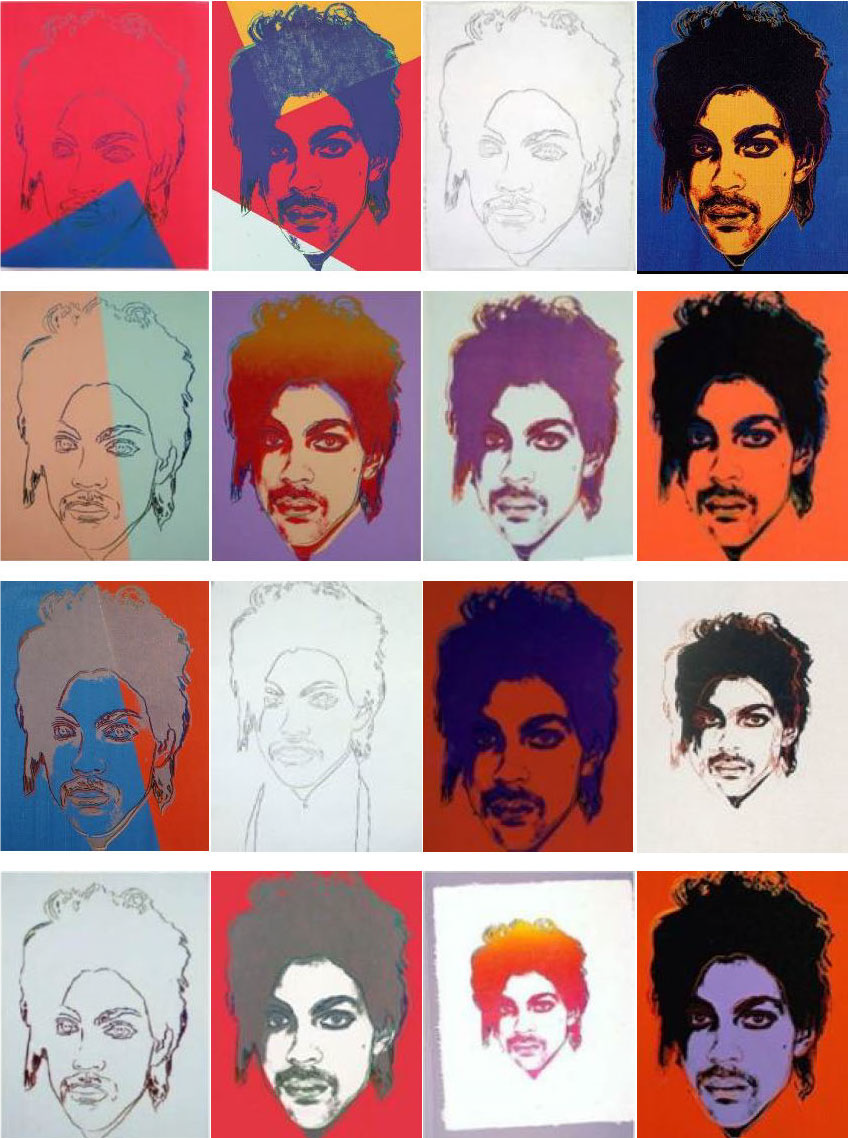

Unbeknownst to Goldsmith, the artist that Vanity Fair commissioned to create the illustration was Andy Warhol. He created 14 silkscreen prints and two pencil drawings based on the photo, presumably to give the editors a choice of illustrations for the magazine. (The Court reproduced thumbnails of the entire “Prince Series” in an Appendix, shown below.) Vanity Fair selected one of the illustrations to accompany its article, titled “Purple Fame.” The magazine issue included the credit “source photograph © 1984 by Lynn Goldsmith/LGI.”

[Figure 2, slip op. at 5]

Warhol died three years later at age 58. The Andy Warhol Foundation (AWF) sold 12 of the works in the “Prince Series” to collectors and galleries, and it transferred custody of the remaining four to the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. There is no evidence in the record that Warhol was aware of the single-use restriction in the license.

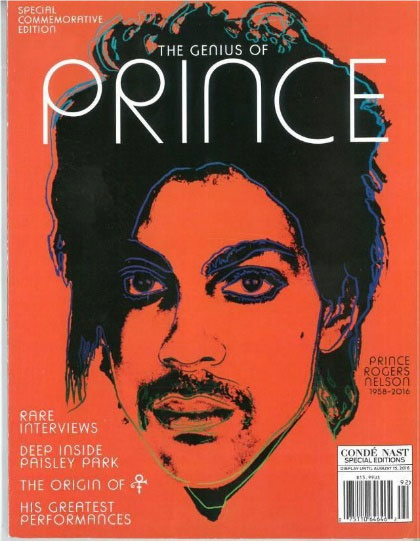

Fast-forward three decades. When Prince died in 2016, Condé Nast contacted AWF for permission to re-publish the 1984 illustration in a special issue devoted to Prince. When the publishers learned of the Prince Series, they decided to use Orange Prince instead. Condé Nast paid AWF $10,000 for a license to reproduce Orange Prince on the cover of the “Special Commemorative Issue.” “Goldsmith received neither a fee nor a source credit.” [Slip op. at 6]

[Figure 3, slip op. at 6]

When Goldsmith saw the commemorative issue, she recognized the cover was based on one of her photos and, for the first time, learned of the existence of the Prince Series. She contacted AWF and advised it that the illustration infringed her copyright. Two months later, in November 2016, she registered her copyright in the photograph with the U.S. Copyright Office.

The Road Not Taken

At this point, no lawsuit had been filed; and the dispute probably could have been, and certainly should have been, easily resolved. Because she failed to register her copyright until after the infringement commenced, Goldsmith is ineligible to recover either statutory damages or attorneys’ fees. [17 U.S.C. 412] After thirty years, employees at both AWF and Condé Nast had either forgotten or, more likely, had never even known that the Warhol portraits were based on a specific photo, that the photo had been licensed, or that it was limited to a one-time use. (It is barely possible that an employee who was aware of the 1984 issue saw the photo credit and deliberately ignored it, but that seems far less likely. Goldsmith herself had been entirely unaware of the licensed use.) Condé Nast had paid $10,000 to AWF; Goldsmith likely would have accepted a similar amount to license the cover illustration after the fact. Both parties were no doubt concerned about AWF’s sales of the 16 originals and past and future licensing of reproductions of the Prince Series, but a sincere apology and good-faith negotiations may have resulted in a win-win situation for all concerned.

Instead, AWF unwisely decided to go on the offensive. In April 2017, it filed a lawsuit against Goldsmith and her agency (now known as Lynn Goldsmith, Ltd., or LGL), seeking a declaratory judgment of non-infringement and/or fair use for the entire Prince Series. Goldsmith responded with a counterclaim of copyright infringement. (Significantly, Goldsmith did not add Condé Nast as a party to its counterclaim, even though it was the party that had agreed to the single-use restriction.)

Several points are worth reiterating here. First, Condé Nast had a license to create and publish the illustration published in Vanity Fair in 1984. Second, that license allowed Condé Nast to use a freelance artist, so Warhol had a valid sublicense to create that illustration (known as Purple Prince). Third, Warhol likely created the 16 originals to give Vanity Fair a choice of illustrations, which may implicitly have been authorized by the license (based on custom and practice in the industry). Fourth, there is no evidence that Warhol was aware of the single-use restriction, so even assuming the 15 additional portraits were unauthorized, he was very likely an innocent infringer. Fifth, as a result of Warhol’s death, AWF was almost certainly an innocent infringer as well. Although copyright infringement is a strict liability tort, all of these facts might have helped to convince Goldsmith to settle on reasonable terms, and all of them would have made AWF a more sympathetic defendant in the unlikely event that Goldsmith pursued her claims and a trial was needed.

Instead, AWF unwisely threw all of its advantages away by going on the offensive and picking a fight that might never have occurred. By taking the offensive, AWF made itself look like a bully: the estate of a wealthy artist taking advantage of an individual photographer, who was just trying to make a living by licensing her work. The true facts were less one-sided; Goldsmith was a successful photographer in her own right, well known in professional circles, even if not to the general public. But unless AWF could paint Goldsmith as a copyright “troll” (which didn’t fit the facts), she was always going to have a David-versus-Goliath story to tell. By suing first, AWF made it much easier to argue that Goliath had picked a fight with David.

To be fair, we don’t know for certain that Goldsmith would have been willing to settle on reasonable terms had AWF been more conciliatory. Perhaps she simply got unreasonably greedy when she discovered the infringer was Warhol rather than an unknown artist. (If so, I have seen no evidence of that in public record; and the subsequent procedural posture suggests otherwise.) But in any event, AWF’s aggressive, take-no-prisoners approach made a friendly settlement all but impossible. As a result, the rest of the copyright ecosystem has to live with the fallout from AWF’s seemingly reckless and irresponsible litigation strategy.

Legal Background: Fair Use and the Supreme Court

As readers familiar with copyright law are aware, the Copyright Act states simply that “the fair use of a copyrighted work … is not an infringement of copyright.” [17 U.S.C. § 107] The statute leaves it up to courts to decide on a case-by-case basis whether a particular use is “fair.” It provides two sources of guidance: first, it lists six examples: “for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching …, scholarship, and research.” Those six purposes are not exclusive, nor are they automatically fair uses; they are simply examples of uses that are more likely to be fair under the circumstances. Second, the statute lists four factors for courts to consider “in determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use”:

(1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

(2) the nature of the copyrighted work;

(3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

(4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

This is the familiar four-factor test for fair use. In copyright opinions, courts routinely discuss the four factors in numerical order before reaching a conclusion. (In practice, most courts make a gut-level decision whether a particular use is “fair,” and then write an opinion to justify their intuition. Such result-oriented reasoning is usually considered improper, but arguably it is appropriate when the statutory question is whether or not a particular use is “fair.”) [Eric’s comment: I note Prof. Barton Beebe’s empirical work on this topic.]

Before 2020, the Supreme Court decided only four fair use cases. In the first, Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc., 464 U.S. 417 (1984), the Court held 5-4 that home recording of broadcast television programs to watch at a later time (time-shifting) was a fair use. Addressing Factor 1, it explained that “time-shifting for private home use must be characterized as a noncommercial, nonprofit activity.” (Id. at 449). Addressing Factor 4, it asserted there was little or no market harm, because “time-shifting merely enables a viewer to see … a work which he had been invited to witness in its entirety free of charge.” (Id. at 450) (Skipping commercials was not yet feasible, id. at 452 n.36, because remote controls did not exist.) Those factors outweighed the facts that the copyrighted works were highly creative motion pictures and television programs (Factor 2), being copied in their entirety (Factor 3) for entertainment purposes (Factor 1).

Sony marked the first time the Court actually decided a fair use case (two earlier efforts had ended with affirmances by an equally divided Court, with no written opinion). Sony also marked the first time the Court confronted a new technology that made it possible for the general public to copy entire works with ease; and Sony’s decision to extend fair use to permit copying of entire works was extremely controversial. It is probably no coincidence that the Court’s decision to grant certiorari in the second fair use case came just four months after the decision in Sony.

In Harper & Row Publishers, Inc. v. Nation Enterprises, 471 U.S. 439 (1985), Harper & Row paid former President Gerald Ford to write and publish an autobiography. A few weeks before it could do so, however, someone brought a stolen copy of the manuscript to The Nation magazine, which hastily published a 2,250-word excerpt summarizing Ford’s thoughts about his pardon of former President Richard Nixon. As a result, Time magazine canceled its contract to publish a 7,500-word excerpt shortly before the book’s publication.

The Court held 6-3 that The Nation’s article was not a fair use. On Factor 1, although the use involved news reporting (one of the six statutory examples), that purpose was outweighed by The Nation’s intended purpose of “scooping” the Time magazine excerpt and “knowingly exploited a purloined manuscript.” (Id. at 563) On Factor 2, although “[t]he law generally recognizes a greater need to disseminate factual works than works of fiction or fantasy” (id. at 563), that was outweighed by the fact that the copied work was previously unpublished, which was “a critical element of its nature” (id. at 563). On factor 3, although The Nation copied verbatim only about 300 words, “an insubstantial portion” of the 200,000-word manuscript in percentage terms, that was outweighed because qualitatively, “[T]he Nation took what was essentially the heart of the book,” namely, the chapter about the Nixon pardon. (Id. at 564-65) Finally, Factor 4 “must take account not only of harm to [the market for] the original [book] but also of harm to the market for derivative works” (id.), such as the $12,500 that Harper & Row lost when Time canceled its prepublication excerpt.

Harper & Row was seen by many as a course correction or balance to Sony, reinforcing the idea that, in general, reproduction for the same purpose as the original was not a fair use. Unfortunately, however, Harper & Row was not a typical fair use case either. Bad facts make bad law; and in Harper & Row, bad timing and the stolen manuscript were likely dispositive. Everyone agrees that quoting excerpts in a book review is a fair use, as long as the quotes are reasonably limited. Had the same article been published after the book was put on sale, rather than a few weeks before, the case almost certainly would have come out the other way.

The Court’s third fair use decision is little remembered today; or rather, it is remembered primarily for the other issue that it decided, concerning renewal terms under the 1909 Copyright Act. In Stewart v. Abend, 495 U.S. 207 (1990), the Court held 6-3 that because the movie Rear Window (1954) was a derivative work, based upon a short story by Cornell Woolrich, the copyright owners in the movie could not continue to exploit the movie during the renewal term of the copyright without the permission of Woolrich’s successor-in-interest, the owner of the copyright in the short story. In a coda, however, the Court also rejected the argument that the movie was a fair use of the short story. It held that “all four factors point to unfair use,” and it agreed with the Ninth Circuit that “[t]his case presents a classic example of an unfair use: a commercial use of a fictional story that adversely affects the story owner’s adaptation rights.” 495 U.S. at 238A.

The Court’s fourth fair use decision was the landmark opinion in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569 (1994), in which the Court unanimously held that a raunchy rap-music version of the popular song Pretty Woman (with altered lyrics) was a parody and was likely a fair use. In so holding, it completely “transformed” the analysis of the first factor (pun intended). The Court explained:

The central purpose of [the first factor] is to see … whether the new work merely supersedes the objects of the original creation (supplanting the original), or instead adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message; it asks, in other words, whether and to what extent the new work is “transformative.” Although such transformative use is not absolutely necessary for a finding of fair use, the goal of copyright, to promote science and the arts, is generally furthered by the creation of transformative works. Such works thus lie at the heart of the fair use doctrine’s guarantee of breathing space within the confines of copyright, and the more transformative the new work, the less will be the significance of other factors, like commercialism, that may weigh against a finding of fair use.

Id. at 579 (citations and quote marks omitted).

Applying this standard, the Court held “parody has an obvious claim to transformative value,” because “it can provide social benefit, by shedding light on an earlier work, and, in the process, creating a new one.” Id. It defined a parody as “a “literary or artistic work that imitates the characteristic style of an author or a work for comic effect or ridicule” (id. at 580), and it contrasted parody with satire, defined as a work “in which prevalent follies or vices are assailed with ridicule,” or are “attacked through irony, derision, or wit.” (Id. at 581 n.15) It said: “Parody needs to mimic an original to make its point, and so has some claim to use the creation of its victim’s imagination, whereas satire can stand on its own two feet and so requires justification for the very act of borrowing.” (Id. at 580-81 (parenthetical omitted)) Crucially, however, it did not disqualify satire from fair use; it only indicated (in dicta) that satire would require more of a “justification” to qualify. (Id. at 580-81 & n.14, 592 n.22)

(Many courts oversimplified the holding, drawing a sharp distinction between “parody (in which the copyrighted work is the target) and satire (in which the copyrighted work is merely a vehicle to poke fun at another target)” and categorically disqualifying satire from fair use. See, e.g., Dr. Seuss Enterprises, L.P. v. Penguin Books USA, Inc., 109 F.3d 1394, 1400 (9th Cir. 1997). I have strongly criticized that distinction. See Ochoa, Dr. Seuss, the Juice and Fair Use: How the Grinch Silenced a Parody, 49 J. Copyr. Soc’y USA 546 (1998). Over the next 20 years, other courts slowly began to erode the distinction. See Ochoa, Dr. Seuss, the Juice and Fair Use Revisited, 59 IDEA 233 (2018).)

In the three decades since Campbell, the “transformative” use inquiry has become central to fair use–so much so that, contrary to Campbell’s nuanced approach, most lower courts have treated the inquiry as essentially dispositive of the fair use inquiry. During that time, the lower courts also increasingly made a subtle but important shift: although Campbell appeared to hold that the content of the allegedly infringing work was “transformative” of the copyrighted work, many important Court of Appeal opinions have asked instead whether the purpose of the allegedly infringing work was “transformative” compared with the purpose of the copyrighted work. This shift is consistent with the statutory phrase “the purpose and character of the use,” (emphasis added); and, as we will see, the majority in the Warhol case blessed this interpretation.

To summarize the rest of Campbell briefly: the second factor “is not much help … in a parody case, since parodies almost invariably copy publicly known, expressive works.” (510 U.S. at 586) On the third factor, “[a] parody must be able to ‘conjure up’ at least enough of [the] original to make the object of its critical wit recognizable.” (Id. at 588, emphasis added). On the fourth factor, “[t]he market for potential derivative uses includes only those that creators of original works would in general develop or license others to develop.” (Id. at 592) Thus, “it is more likely that [a parody] will not affect the market for the original in a way cognizable under this factor, that is, by acting as a substitute for” the original or for licensed derivatives (here, a hypothetical non-parody rap version of Pretty Woman). (Id. at 591)

More than 25 years later, the Court finally took a fifth fair use case: Google v. Oracle, 141 S.Ct. 1183 (2021). In that technologically complex case, the Court (absent Justice Ginsburg or her replacement, Justice Barrett) held 6-2 that Google’s use of the names and organization of the packages, classes, and methods in Oracle’s Java SE Application Program Interface (API) software, as embodied in thousands of lines of declaring code, was a fair use, where Google reimplemented those methods by writing its own implementing code. (If that sentence doesn’t make sense to you, you’re probably not alone: you can read my explanation of the technology and the holding.)

Although Google v. Oracle simply restored the status quo as far as the software industry was concerned, outside of the software industry it was an extremely controversial decision. Many copyright owners could not believe that the Supreme Court allowed a fierce competitor of the copyright owner to copy an essential (and creative) part of a copyrighted work for the purpose of competing with the copyright owner in a potential derivative market (in that case, the market for software for cell phones). Thus, when the Supreme Court granted certiorari in the Warhol case less than a year after the Google v. Oracle decision, I made a tentative prediction (in an email discussion list among law professors):

The Supreme Court rarely takes cases in order to affirm them; but in this instance, it wouldn’t surprise me if that was exactly what they might be doing (or planning on doing).

Recall the Sony Betamax case, which was controversial because it said you could copy the entire work, without change, for the same purpose, and it could still be a fair use. (Arguably little to no market harm, at least not until remote controls and commercial-skipping became popular.) A few months later, the Supreme Court granted cert. in Harper & Row, ultimately holding that it was NOT a fair use to copy a small portion of a soon-to-be-published work, for what was arguably “news reporting” (but no real urgency). Harper & Row was widely seen as a corrective or balance to Sony (albeit one that perhaps went too far in the opposite direction).

Eldred upheld copyright term extension; and later that same year, the Court granted cert. in Dastar (an UNPUBLISHED decision [below]), ultimately holding that the Lanham Act does not prohibit copying a work of authorship (here, one that was in the public domain). The dicta in Dastar, that Congress cannot grant a perpetual copyright (even under the guise of the Lanham Act), was widely seen as a corrective or balance to Eldred.

Now we have Google v. Oracle, a decision that makes economic policy sense, but arguably makes a hash of fair use. (I rarely agree with Justice Thomas on anything, but he’s right when he says the majority opinion only makes sense if one believes, as I do, that the declaring code was not or should not have been copyrightable in the first place.) I wouldn’t be at all surprised if some members of the Google majority joined the two dissenters in granting cert. so they could indicate that Google v. Oracle is essentially limited to its facts (or at least limited to computer software).

If so, however, it is a risky strategy, as other members of the Court (a majority?) might vote to reverse. But this Court doesn’t strike me as particularly Warhol-friendly. Offhand, I don’t see five votes to reverse, especially without Justice Breyer to wrangle them.

Thus, when the Warhol decision was announced, I was feeling remarkably prescient. Although the majority opinion in Warhol does NOT say anything about limiting Google v. Oracle to software, Note 18 does suggest that Google v. Oracle should be read narrowly; and the entire tenor of the majority opinion (and the Gorsuch concurrence) is that fair use decisions should be (and are) narrow and extremely context-specific.

The Procedural Posture Narrows the Case

In the district court, AWF moved for summary judgment, seeking a declaratory judgment that none of the 16 works in the Prince Series infringed the copyright in the Goldsmith photo. Goldsmith moved for summary judgment, seeking a ruling that all of the 16 works in the Prince Series infringed her copyright. Although her counterclaim included the creation of the 15 additional originals, the District Court’s opinion indicated that Goldsmith was willing to forego that part of her claim:

Goldsmith alleges as one theory of infringement that Warhol, or his agents, reproduced her entire photograph, including its protectible and unprotectible elements, without authorization at some point during Warhol’s process of creating the Prince Series. Although this a valid basis for an infringement claim, it relates to conduct that occurred nearly forty years ago and is well outside the Copyright Act’s statute of limitations. Goldsmith appears to recognize this, and focuses her infringement claim primarily on AWF’s more recent licensing of the Price Series works — namely, the 2016 license to Condé Nast and the claim by AWF that it has the right to continue licensing the Prince Series works.

382 F. Supp. 3d 319, 324 (S.D.N.Y. 2019) (citations omitted). Although Goldsmith’s lawyers pleaded the discovery rule (id. at 322), apparently they did not contend that it saved the claim based on the initial creation in 1984 (id. at 324 n.4).

This case thus intersects with a circuit split concerning the Copyright Act’s three-year statute of limitations [15 U.S.C. 507(a)]. Under the discovery rule of accrual, Goldsmith could have recovered damages for all infringements, no matter how old, as long as she filed suit within three years of the date that she discovered, or reasonably should have discovered, of the existence of her claim. (Her actual discovery date in 2016 is uncontested; whether she reasonably should have discovered the Prince Series at an earlier time is disputed.) In 2020, however, the Second Circuit held (in a different case) that even if the discovery rule applies, damages are limited to a three-year “lookback” period. That ruling made no sense as a matter of logic (see my criticism here), and the Ninth Circuit properly rejected it just last year (as explained here). The Eleventh Circuit has now joined the Ninth Circuit (opinion here), and a petition for certiorari is pending. If the Supreme Court takes the case, however, it will be writing on a clean slate concerning the discovery rule. Although I have been an advocate for the discovery rule, the Warhol case is a striking example of the potential unfairness of allowing claims based on decades-old activity.

In granting AWF’s summary judgment motion, the district court held that it “need not address” whether the works were substantially similar, “because it is plain that the Prince Series works are protected by fair use.” 382 F. Supp. 3d at 324 (emphasis added). Addressing the first factor, it held that although the Prince Series works were commercial, they were also “transformative.” In particular, the works could “reasonably be perceived to have transformed Prince from a vulnerable, uncomfortable person to an iconic, larger-than-life figure,” so that “each Prince Series work is immediately recognizable as a ‘Warhol’ rather than as a photograph of Prince.” Id. at 326. Although Goldsmith’s work was creative and unpublished, the second factor was “of limited importance because the Prince Series works are transformative.” Id. at 327. The third factor favored AWF, because “Warhol removed nearly all the photograph’s protectible elements in creating the Prince Series.” Id. at 330. The fourth factor also favored AWF because “the licensing market for Warhol prints … is distinct from the licensing market for photographs like Goldsmith’s.” Id. at 331. (The latter three rulings could each be the subject of a lengthy blog post; but because they played no role in the Supreme Court’s decision, we must forego those discussions for now.)

On appeal, the Second Circuit reversed and remanded, holding that “the Prince Series works are substantially similar to the Goldsmith Photograph as a matter of law,” and that “the Prince Series works are not fair use as a matter of law.” 11 F.4th 26, 32 (2d Cir. 2021). On the first factor, “we conclude that the Prince Series is not ‘transformative’ within the meaning of the first factor.” Id. at 42. “[This] is not to deny that the Warhol works display the distinct aesthetic sensibility that many would immediately associate with Warhol’s signature style,” but nonetheless, “the overarching purpose and function of the two works at issue here is identical, not merely in the broad sense that they are created as works of visual art, but also in the narrow but essential sense that they are portraits of the same person.” Id. More broadly, it opined that “there exists an entire class of secondary works that add ‘new expression, meaning, or message’ to their source material, but may nonetheless fail to qualify as fair use: derivative works.” (Id. at 39) [In its original opinion, it had erroneously stated that derivative works are “nonetheless specifically excluded from the scope of fair use” 992 F.3d 99, 111 (2d Cir. 2021) (emphasis in original); it retreated from that position after AWF’s petition for rehearing.] Because Goldsmith’s photo was both creative and unpublished, the second factor also favored her. 11 F.4th at 45. On the third factor, “the Prince Series borrows significantly from the Goldsmith Photograph, both quantitatively and qualitatively.” Id. at 47. On the fourth factor, “what encroaches on Goldsmith’s market is AWF’s commercial licensing of the Prince Series, not Warhol’s original creation[s].” Id. at 51. Overall, it held that “just as artists must pay for their paint, canvas, neon tubes, marble, film, or digital cameras, if they choose to incorporate the existing copyrighted expression of other artists …, they must pay for that material as well.” Id. at 52.

Concurring, Judge Jacobs emphasized the narrow scope of the case:

[Our] holding does not consider, let alone decide, whether the infringement here encumbers the [sixteen] original Prince Series works that are in the hands of collectors or museums…. This case does not decide their rights to use and dispose of those works because Goldsmith does not seek relief as to them. She seeks damages and royalties only for licensed reproductions of the Prince Series…. Although the Andy Warhol Foundation initiated this suit with a request for broader declaratory relief that would cover the original works, … Goldsmith does not claim that the original works infringe and expresses no intention to encumber them; the opinion of the Court necessarily does not decide that issue. (Id. at 54-55)

Procedurally, this judicial restraint makes sense: federal courts may only decide “cases or controversies” that are actually contested by the parties. But substantively, it was a strange line to draw. After all, any “licensed reproductions of the Prince Series” necessarily would contain the same “new expression, meaning, or message” as the sixteen originals.

AWF’s petition for certiorari limited the Question Presented to the first fair use factor, in order to present a clear circuit split to the Court: “Whether a work of art is ‘transformative’ when it conveys a different meaning or message from its source material (as this Court, the Ninth Circuit, and other courts of appeals have held), or whether a court is forbidden from considering the meaning of the accused work where it “recognizably deriv[es] from” its source material (as the Second Circuit has held).” [Petition at i] This strategic decision limited the scope of the case even further.

The Majority Opinion

Justice Sotomayor’s majority opinion began its analysis by emphasizing that the Question Presented was narrow: “Although the Court of Appeals analyzed each fair use factor, the only question before this Court is whether the court below correctly held that the first factor … weighs in Goldsmith’s favor.” [Slip op. at 12 (emphasis added)] It then further narrowed the scope of the case by eliminating most of the works in the Prince Series from consideration: “Here, the specific use of Goldsmith’s photograph alleged to infringe her copyright is AWF’s licensing of Orange Prince to Condé Nast.” [Id. (emphasis added)]

Having restated the Question Presented, the majority answered it in general terms: “the first fair use factor … focuses on whether an allegedly infringing use has a further purpose or different character, which is a matter of degree, and the degree of difference must be weighed against other considerations, like commercialism. Although new expression may be relevant to whether a copying use has a sufficiently distinct purpose or character, it is not, without more, dispositive of the first factor.” [Id. (citation omitted)]

This cautious and seemingly innocuous conclusion disguises two ways in which the majority opinion differs from the prevailing view of fair use. First, the opinion states that “new expression may be relevant” to the first factor (emphasis added), rather than stating that it is relevant to the first factor, or even that it usually or almost always is relevant. Second, the actual Question Presented technically did not ask whether new expression was “dispositive” of the first factor; instead, it asked whether new expression rendered a use “transformative” or not (which the parties clearly assumed would be dispositive of the first factor). The majority could have answered that question in the affirmative (preserving its existing case law), while still holding that the transformative character of the Warhol works was outweighed by other considerations, so that it was not dispositive of the first factor, or of fair use in general.

Instead, after briefly summarizing the general outlines of the fair use doctrine, the majority opinion took a scalpel to its Campbell precedent. In restating its unanimous holding in Campbell, the majority opinion states:

The “central” question [the first factor] asks is “whether the new work merely ‘supersede[s] the objects’ of the original creation . . . (‘supplanting’ the original), or instead adds something new, with a further purpose or different character.” Campbell, 510 U. S., at 579…. In that way, the first factor relates to the problem of substitution—copyright’s bête noire. The use of an original work to achieve a purpose that is the same as, or highly similar to, that of the original work is more likely to substitute for, or “‘supplan[t],’” the work, ibid. (Slip op. at 15, citations omitted)

Compare this to the actual language of Campbell: immediately after the word “character” the Campbell opinion added a comma, followed by: “altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message; it asks, in other words, whether and to what extent the new work is ‘transformative.’” 510 U. S. at 579. Thus, not only did the Campbell opinion specifically identify “new expression, meaning, or message” as one of the considerations that gave a work “a further purpose or different character,” it also expressly labelled such an alteration as “transformative.” That language alone should have been enough to answer the original Question Presented in AWF’s favor, even if the majority wanted to affirm the judgment on other grounds.

Two paragraphs later, the majority opinion slips another misleading omission into an otherwise uncontroversial paragraph:

Whether a use shares the purpose or character of an original work, or instead has a further purpose or different character, is a matter of degree. Most copying has some further purpose, in the sense that copying is socially useful ex post. Many secondary works add something new. That alone does not render such uses fair. Rather, the first factor (which is just one factor in a larger analysis) asks “whether and to what extent” the use at issue has a purpose or character different from the original. Campbell, 510 U. S., at 579 (emphasis added). The larger the difference, the more likely the first factor weighs in favor of fair use. The smaller the difference, the less likely. (Slip op. at 15-16)

This passage would be unobjectionable, except for one crucial omission: what the Campbell Court actually asked was “whether and to what extent the new work is ‘transformative.’” 510 U.S. at 579 (emphasis added). The majority opinion in Warhol, by contrast, focuses on “the use at issue” and steadfastly avoids quoting the language that Campbell actually used. The majority opinion in Warhol should have accepted the language of Campbell at face value and instead explained why, and under what circumstances, the creation of a “transformative” work should sometimes be outweighed by other considerations.

What makes the majority opinion’s sleight of hand worse is that it was entirely unnecessary. Yes, “the problem of substitution” was one of the concerns that Campbell attempted to address; but one could make that point without altering Campbell’s language. Moreover, Campbell itself contains plenty of qualified language that allows for flexible application of its ideas. (Indeed, in the sentence immediately following the passage quoted above, the Campbell Court hedged, carefully saying only that “the goal of copyright, to promote science and the arts, is generally furthered by the creation of transformative works.” 510 U.S. at 579 (emphasis added).)

After deliberately avoiding the inconvenient language in Campbell for four pages, the majority finally confronts the problem: “the word ‘transform,’ though not included in §107, appears elsewhere in the Copyright Act,” namely, in the definition of a “derivative work” in §101. [Slip op. at 16] That means that the exclusive right to prepare derivative works in §106(2) includes “the right to derivative transformations of her work.” [Id.] So “an overbroad concept of transformative use, one that includes any further purpose, or any different character, would narrow the copyright owner’s exclusive right to create derivative works. To preserve that right, the degree of transformation required to make [a] ‘transformative’ use of an original must go beyond that required to qualify as a derivative.” [Id.]

One is tempted to respond of course fair use “narrow[s] the copyright owner’s exclusive right to create derivative works.” As the majority opinion acknowledges, all of the §106 rights are expressly “[s]ubject to” §107. What the Court apparently means is that “an overbroad concept of transformative use … would unduly narrow” the derivative work right, a statement I imagine many copyright scholars would agree with. The problem, of course, lies in defining the terms “overbroad” and “unduly narrow,” a matter about which reasonable people (including copyright scholars) can emphatically disagree.

After summarizing the facts and holding in Campbell, the majority then drew two lessons from that opinion. First, although “[t]he commercial nature of the use is not dispositive,” (a proposition the majority in Campbell had worked hard to establish), “it is relevant.” (Slip op. at 18 (emphasis added)) Second, the majority returned to Campbell’s distinction “between parody (which targets an author or work for humor or ridicule) and satire (which ridicules society but does not necessarily target an author or work).” (Slip op. at 17) From this it drew the conclusion that “the first factor also relates to the justification for the use. (Id.) In particular, “a use may be justified because copying is reasonably necessary to achieve the user’s new purpose.” (Slip op. at 18) Specifically, “commentary or criticism that targets an original work may have compelling reason to ‘conjure up’ the original by borrowing from it.” (Slip op. at 19, emphasis added)

This is quite a narrow view of fair use. Although Campbell drew a distinction between parody and satire, it did not hold that satire was ineligible for fair use treatment; it only held that, in some circumstances, satire would require a greater justification for the borrowing. In particular, the Campbell court indicated that “looser forms of parody” and “satire” would pass muster in circumstances “when there is little or no risk of market substitution, whether because of the large extent of transformation of the earlier work, [or] the small extent to which [the new work] borrows from an original.” 510 U.S. at 581 n.14. By contrast, the majority opinion in Warhol appears to limit fair use to new uses that “target an original work,” and even then, the user must “have a compelling reason to ‘conjure up’ the original” (emphasis added).

There is also a danger that this passage may be conflated with the types of “compelling” reasons that justify government restrictions on fundamental rights, including free speech. When the government seeks to restrict fundamental rights, it must have a “compelling” justification for doing so. But in copyright law, it is the copyright owner that seeks to use the power of the government (namely, the courts) to restrict the speech of others. Here, the Court suggests that the secondary user must have a compelling justification to speak, instead of requiring that the copyright owner have a compelling justification for restricting that speech.

Transformative Work or Transformative Use?

In applying the standards it gleaned from Campbell, the majority opinion emphasized again that the case before it concerned only one work in the Prince Series and only one use of that work: namely, “AWF’s commercial licensing of Orange Prince to Condé Nast” in 2016 for the cover of the “Special Commemorative Issue” devoted to Prince. (Slip op. at 21)

Herein lies one of the fundamental disagreements between the majority and the dissent. If a derivative work is deemed to be a “transformative” use of the original work, and therefore a fair use, does that determination extend to all subsequent uses of the derivative work? Or must each use of the derivative work be assessed to determine whether that particular use is also a “transformative” purpose of the original?

In most cases involving parody and other types of “appropriation art,” courts usually have asked whether the allegedly infringing work was transformative or not [Dissent, slip op. at 2], and if so, they seem to have assumed that all uses of that work would likewise be considered transformative. But in cases involving new technologies, court typically have asked whether the allegedly infringing uses were fair use or not. In Sony, for example, videotaping a broadcast television program for time-shifting purposes was held to be a fair use; there was certainly no indication that the copy lawfully made for that purpose could then be leased or sold to others. [Majority op. at 20-21]

The distinction between transformative works and transformative uses also was critical to the concurring opinion by Justice Gorsuch, joined by Justice Jackson. “By its terms, the law trains our attention on the particular use under challenge. And it asks us to assess whether the purpose and character of that use is different from (and thus complements) or is the same as (and thus substitutes for) a copyrighted work.” (Concurring op. at 2, emphasis added)

The majority observed that “[a] typical use of a celebrity photograph is to accompany stories about the celebrity, often in magazines.” (Slip op. at 22) It then held that, in the context of the 2016 Commemorative magazine, “the purpose of the image [of Orange Prince] is substantially the same as that of Goldsmith’s photograph. Both are portraits of Prince used in magazines to illustrate stories about Prince.” (Slip op. at 22-23) Because the purpose of the use was the same as the purpose of the underlying work, the use was not “transformative.” And because AWF licensed the image for money, the use was also commercial. (Slip op. at 24) Taken together, those two elements “counsel against fair use, absent some other justification for copying.” (Slip op. at 25)

Much of the remainder of the majority opinion is devoted to rebutting the dissent’s compelling argument that Warhol’s work was transformative because it contained “new expression, meaning, or message.” The majority reiterated a point it made earlier: if “new expression, meaning, or message” was enough for the first factor to weigh in favor of fair use, “‘transformative use’ would swallow the copyright owner’s exclusive right to prepare derivative works.” (Slip op. at 28) But in attempting to avoid assessing the “meaning” of Warhol’s work, the majority opinion reached absurd levels of self-contradiction. At one point, the majority says:

A court should not attempt to evaluate the artistic significance of a particular work. Nor does the subjective intent of the user (or the subjective interpretation of a court) determine the purpose of the use. But the meaning of a secondary work, as reasonably can be perceived, should be considered to the extent necessary to determine whether the purpose of the use is distinct from the original, for instance, because the use comments on, criticizes, or provides otherwise unavailable information about the original. [Slip op. at 31-32]

But just two paragraphs later, the majority says: “whether a work is transformative cannot turn merely on the stated or perceived intent of the artist or the meaning or impression that a critic—or for that matter, a judge—draws from the work.” (Slip op. at 32) So how is a court supposed to determine what “meaning .. reasonably can be perceived” in a work if it can’t rely on the meaning that a critic or a judge can perceive in the work? Are courts supposed to take opinion polls of viewers to determine what meanings they perceive, unaided by critics or jurists?

The majority did hold (find?) that, even assuming that Warhol’s work contained new expression, meaning, or message, “it ‘has no critical bearing on’ Goldsmith’s photograph.” (Slip op. at 34) It explained:

At no point in this litigation has AWF maintained that any of the Prince Series works … comment on, criticize, or otherwise target Goldsmith’s photograph. That makes sense, given that the photograph was unpublished when Goldsmith licensed it to Vanity Fair, and that neither Warhol nor Vanity Fair selected the photograph, which was instead provided by Goldsmith’s agency. (Slip op. at 34 n.20)

In other words, Warhol could have used any photograph of Prince to express his message; and indeed, he played no role in choosing the photograph that he did use. In the majority’s view, since the photo is not itself the target of Warhol’s message (whatever it may be), Warhol needed to proffer a justification for using it. “Yet AWF offers no independent justification, let alone a compelling one, for copying the photograph, other than to convey a new meaning or message.” (Slip op. at 35)

In concluding, the majority summarizes its major points: copyright “includes the right to prepare derivative works that transform the original.” Goldsmith’s photo and AWF’s licensed image of Orange Prince “share substantially the same purpose, and the use is of a commercial nature. AWF has offered no other persuasive justification for its unauthorized use of the photograph. Therefore, the [first factor] weighs in Goldsmith’s favor.” (Slip op. at 38) Since AWF did not appeal any of the other factors, the Second Circuit’s judgment was affirmed.

The Dissenting Opinion

Justice Kagan, joined by Chief Justice Roberts, dissented. After her introduction, the next seven pages of her opinion are devoted (indeed the right word) to a fawning appreciation of Warhol’s technique, his works, and his place in art history. [She misses her target in one respect: in describing “the laborious and painstaking work that Warhol put into these and other portraits” (Dissent, at 9), she praises the one element of his contribution (“sweat of the brow”) that cannot form the basis for copyright protection. Feist Publications, Inc. v. Rural Telephone Service Co., 499 U.S. 340, 352-54 (1991).] She is correct in the conclusion that she draws from Campbell: “Under established copyright law (until today), Warhol’s addition of important “new expression, meaning, [and] message” counts in his favor in the fair-use inquiry.” (Dissent, at 11) And she is dismissive of the majority’s approach to purpose and character: “All of Warhol’s artistry and social commentary is negated by one thing: Warhol licensed his portrait to a magazine, and Goldsmith sometimes licensed her photos to magazines too. That is the sum and substance of the majority opinion.” (Dissent, at 18)

Justice Kagan’s dissent ranges far afield in praising “‘appropriation, mimicry, quotation, allusion and sublimated collaboration’ … cutting across all forms and genres in the realm of cultural production.” (Dissent, at 25) She invokes example after example of artists who borrowed from others, in literature (Shakespeare, Vladimir Nabokov, Robert Louis Stevenson), music (from Mozart, Beethoven and Stravinsky to Charlie Parker and Bob Dylan, although many of her musical examples are things that would not be protected expression in the first place), and then back to multiple examples from art history. Her critique is thorough, but at times Justice Kagan appears to be at war with the very concept of derivative works. If all of these derivative works are transformative and are fair uses, how is a court supposed to tell the difference between these fair uses and ordinary derivative works that are not fair uses?

Disagreements among friends are sometimes more contentious than disagreements among enemies, and certainly that is the case here. Justice Kagan’s dissent is unusually strident, and Justice Sotomayor’s responses (woven throughout her majority opinion) are unusually defensive. Justice Kagan mentions the majority opinion 110 times in her critique, usually dismissively, complaining that “today’s decision … leaves our first-factor inquiry in shambles.” (Dissent, at 2) She concludes that the majority opinion “will stifle creativity of every sort. It will impede new art and music and literature. It will thwart the expression of new ideas and the attainment of new knowledge. It will make our world poorer.” (Dissent, at 36) In response, Justice Sotomayor’s majority opinion devotes at least 12 footnotes and an entire section (two full pages) to refuting the dissent’s critique, and it dismisses the dissent’s predictions that the majority opinion will stifle creativity: “These claims will not age well. It will not impoverish our world to require AWF to pay Goldsmith a fraction of the proceeds from its reuse of her copyrighted work.” (Slip op., at 36)

Limited Remedies as an Alternative

Obviously, I am in agreement with many of the points made by the strident critics of the majority opinion. So why, then, do I consider myself as “concurring in the judgment”? My reasoning proceeds in several steps. First, I believe the Prince Series works meet the legal definition of derivative works: they were “based upon” the Goldsmith photo, and even though the scope of copyright in photographs is limited, I believe the Warhol works are substantially similar to protected expression in the photo. Second, I believe the Prince Series was created lawfully, primarily because creating 16 alternatives for Vanity Fair to choose from was likely within the scope of the limited license; but if pressed, I would agree with the dissent that the creation of the Prince Series was a fair use. Third, assuming that Warhol created the Prince Series lawfully, and thereby acquired valid copyrights in the Prince Series, the statute expressly says that the copyright in a derivative work covers only the new material added by the second author; meaning that subsequent licensing of reproductions the Prince Series still infringes the copyright in the photo unless the licensed use itself is also a fair use. In other words, I agree with the majority opinion that the creation of a derivative work and the licensing of reproductions of that derivative work logically can be separated. Finally, I believe that Goldsmith, as the creator of the underlying photo, should be entitled to a limited remedy for the use of that photo (namely, a reasonable royalty), even though I would not give her control over the reproductions of the Prince Series by granting her an injunction (except to require credit).

Many commentators have lamented the fact that the fair use doctrine is an all-or-nothing proposition: either a use is a fair use, and therefore non-infringing, or it isn’t, and it is therefore infringing. Those commentators have proposed that there should be an intermediate option, in which the copyright owner is not entitled to prevent or enjoin a particular use, but the user should nonetheless owe the owner a reasonable royalty. Of course, essentially that would amount to a judicially created compulsory license, which perhaps conflicts with the fact that Congress expressly created seven compulsory licenses in the statute itself. But freedom of expression might compel the conclusion that certain derivative uses ought to be allowed to be published, even if the policy underlying copyright law would be to preserve the copyright owner’s incentive to create the original work by granting them a reasonable royalty.

The Court itself has stated several times that an injunction is an equitable remedy that a court may withhold at its discretion. In Sony, the dissent mentioned three times that a finding of infringement did not compel an injunction (against sales of VCRs). (464 U.S. at 460, 494, 499) The Court made the same observation about injunctions in Campbell (510 U.S. at 578 n.10) and in New York Times Co. v. Tasini, 533 U.S. 483, 505 (2001). The Ninth Circuit said the same thing in Abend v. MCA, Inc., 863 F.2d 1495, 1479 (9th Cir. 1988) (the Rear Window case), and on appeal in Stewart v. Abend, the Supreme Court pointedly noted that “the proper remedy … [is] an issue not relevant to the issue on which we granted certiorari.” 495 U.S. at 216. The Supreme Court said it again in Petrella, 572 U.S. at 1978-79 (the Raging Bull case). And a unanimous Court held the same with regard to injunctions in patent cases in eBay, Inc. v. MercExchange, LLC, 547 U.S. 388, 392-93 (2006).

The Supreme Court also suggested in Petrella that an award of defendant’s profits is an equitable remedy, 572 U.S. at 1967 & n.1, 1978, although the statutory codification may make it more difficult to withhold an award of profits, as it provides that the “copyright owner is entitled to recover the actual damages suffered by him or her as a result of the infringement, and any profits of the infringer that are attributable to the infringement.” 17 U.S.C. § 504(b) (emphasis added). But the statute also talks about profits that are “attributable to the infringement,” and the Court has stressed that when profits are awarded, an apportionment of profits is appropriate. Sheldon v. Metro-Goldwyn Pictures Corp., 309 U.S. 390, 402, 407 (1940); Petrella, 572 U.S. at 1973. Although AWF bears the burden on the issue of apportionment, my instinct is that the profits attributable to the infringement in this case are near-zero. Condé Nast wanted to use a Warhol, and the fee that it paid was attributable primarily to Warhol’s contribution (or at least his reputation) and had very little (if anything) to do with Warhol’s source material. Warhol could have used any photograph of Prince, and the works in that hypothetical Prince Series would have been just as valuable as the real-life ones.

As for actual damages, we know what the fair market value of Goldsmith’s photo as an “artist’s reference” was in 1984: $400. That amount should be adjusted upward for inflation, and for the fact that Goldsmith’s own reputation as a celebrity photographer has grown over the years. (Slip op. at 1, 6-8) Her photo is also more valuable today because of Prince’s fame and his untimely death (no more photos can be taken of him, so the supply is limited), although whether that value is attributable to the infringement is doubtful. But it seems reasonable that Goldsmith should be paid a few thousand dollars for her contribution to Orange Prince.

For Goldsmith, the credit for the “source image” may be an even more important consideration. Many artists have indicated that a credit is sometimes at least as important to them, and sometimes more important, than the amount of money they receive (although few artists would be content receiving no money at all; the point of copyright law is to enable artists to make a living by selling and licensing their works). See Jessica Silbey, The Eureka Myth: Creators, Innovators, and Intellectual Property (2014). Thus, I do think an injunction requiring credit when the Warhol images are reproduced would be an appropriate remedy.

Both the Second Circuit and the Supreme Court indicated (albeit implicitly, in dicta) that a reasonably royalty was the proper remedy in this case, rather than an injunction. “If AWF must pay Goldsmith to use her creation, [i]t will not impoverish our world to require AWF to pay Goldsmith a fraction of the proceeds from its reuse of her copyrighted work. Recall, payments like these are incentives for artists to create original works in the first place.” (Slip op. at 36, emphasis in original). “[J]ust as we cannot hold that the Prince Series is transformative as a matter of law, neither can we conclude that Warhol and AWF are entitled to monetize it without paying Goldsmith the ‘customary price’ for the rights to her work.” 11 F.4th at 44-45. “AWF’s licensing of the Prince Series works to Condé Nast without crediting or paying Goldsmith deprived her of royalty payments to which she would have otherwise been entitled.” Id. at 50. “We merely insist that, just as artists must pay for their paint, canvas, neon tubes, marble, film, or digital cameras, if they choose to incorporate the existing copyrighted expression of other artists … (as by using a copyrighted portrait of a person to create another portrait of the same person …), they must pay for that material as well.” Id. at 52.

The dissent responds that “sometimes copyright holders charge an out-of-range price for licenses. And other times they just say no.” (Dissenting op. at 16) But the Court is far more likely to find fair use when there is a market failure of that sort (as there was in Campbell). See Wendy Gordon’s seminal article, Fair Use as Market Failure, 82 Columbia L. Rev. 1600 (1982). By contrast, in Warhol there was a well-functioning derivative market for using photographs as an “artist’s reference” for artistic works. “There currently exists a market to license photographs of musicians, such as the Goldsmith Photograph, to serve as the basis of a stylized derivative image; … if artists “could use such images for free, there would be little or no reason to pay for [them].” 11 F.4th at 50. To borrow a quote from Stewart v. Abend, “[t]his case presents a classic example of an unfair use: a commercial use of a [creative work] that adversely affects the [copyright] owner’s adaptation rights.” 495 U.S. at 238A.

Keeping the most drastic alternatives (an injunction or no remedy at all) on the table may provide both litigants with an incentive to settle for the intermediate position; but it is also possible that it may make it more difficult for litigants to settle cases at all. In this case, for example, if an injunction was off the table, it is highly unlikely that AWF would have chosen to make a federal case over sharing the $10,000 fee that it received; that would truly (but not literally) have been making a mountain out of a molehill. Indeed, had Goldsmith chosen to make a claim herself, such a case might have been more appropriate for the new Copyright Claims Board, where injunctions are unavailable and damages for unregistered works are limited to $7,500 per work infringed. (It is unsurprising that photographers were the biggest users of the Board in early case filings.)

Giving Goldsmith a limited monetary remedy is perhaps more consistent with the natural rights theory of copyright than with the theory that copyright is granted as an incentive to the creation and distribution of new works of authorship. But a focus solely on the creation of new works would undermine the right to prepare derivative works. If we want to have professional photographers, then their copyrights have to be worth something, too. Few artists would be content receiving no money at all when their works are re-used by others. The incentive theory doesn’t have to be applied on a work-by-work basis; it is consistent with the incentive theory that copyright law is to enable artists to make a living in general by selling copies of their works and by licensing them to others to make derivative works.

Reviving the Presumption Against Commercial Uses?

One widespread criticism of the majority opinion (and of the intermediate approach to fair use) is that it potentially revives a particularly pernicious problem in the prior case law: a presumption that commercial uses are almost always unfair. This problem started with dicta in the Sony decision, in which the Court said that “mak[ing] copies for a commercial or profitmaking purpose … would presumptively be unfair” (id. at 449, Factor 1), and “[i]f the intended use is for commercial gain, th[e] likelihood [of market harm] may be presumed.” (Id. at 451, Factor 4). For the next ten years, that dicta weighed heavily against all commercial uses.

Campbell went out of its way to disapprove the dicta in Sony that suggested that all commercial uses were presumptively unfair. In discussing the first factor, the Court said:

The language of the statute makes clear that the commercial or nonprofit educational purpose of a work is only one element of the first factor enquiry into its purpose and character…. [If] commerciality carried presumptive force against a finding of fairness, the presumption would swallow nearly all of the illustrative uses listed in the preamble paragraph of § 107, including news reporting, comment, criticism, teaching, scholarship, and research, since these activities “are generally conducted for profit in this country.” Harper & Row, supra, at 592 (Brennan, J., dissenting). (510 U.S. at 584)

In discussing the fourth factor, it said: “No ‘presumption’ or inference of market harm that might find support in Sony is applicable to a case involving something beyond mere duplication for commercial purposes.” (Id. at 591) Thus, “[i]t was error for the Court of Appeals to conclude that the commercial nature of 2 Live Crew’s parody of “Oh, Pretty Woman” rendered it presumptively unfair.” (Id. at 594) Thus, Campbell returned the “commercial” nature of the use to just one sub-factor to be considered in deciding whether a particular use was fair.

The Warhol opinion, if read too broadly, potentially revives the presumption against commercial uses. The majority repeatedly characterized the Warhol foundation’s use as “commercial licensing.” (Slip op. at 2, 11, 12, 21 & nn. 9-10, 23 n.11, 33), and it repeatedly emphasized that the commercial nature of the use outweighed any “new expression, meaning, or message” that the Warhol works might contain (slip op. at 12, 13, 18, 24, 25, 35, 38). Justice Gorsuch’s concurrence likewise twice stated that AWF’s use was a “commercial substitute” for Goldsmith’s photo. (Concurring op. at 4, 6) The dissent ridiculed this emphasis, saying “All that matters [to the majority] is that Warhol and the publisher entered into a licensing transaction, similar to one Goldsmith might have done.” (Dissenting op. at 3) The majority responded by staying twice that commercial use was “not dispositive” (slip op. at 18, 24), and it avoided using the word “presumption” when referring to the commercial purpose.

Nonetheless, it is hard to avoid the impression that those Justices who make a fetish of purportedly following the “plain language” of a statute were influenced by the fact that the statute specifically mentions “the commercial nature” of the use in Factor 1, but does not mention the word “transformative” except in connection with the definition of a derivative work (as a work that “transform[s]” the original). One hopes that this revived emphasis on the commercial nature of the use will not get out of control, thus requiring another Campbell-like intervention in the near future.

Conclusion

In the five decades since Congress codified fair use, this is not the first time the Supreme Court has reached a fair result but stuffed its opinion with broad statements that are (or may be) liable to cause mischief by stimulating an overbroad reading in the lower courts. (This is partly an occupational hazard, as lawyers reflexively parse and debate the language of fair-use opinions as rigorously as if they were statutes.) Fair use was a mess for a decade after Sony and Harper & Row, so much so that Congress had to step in with a legislative fix for the latter, and the Supreme Court had to “rescue” fair use with its opinion in Campbell. Arguably, Google v. Oracle was poised to cause more confusion. But in attempting to correct course after Google v. Oracle, the Supreme Court may have sent fair use spinning wildly out of control. Time will tell whether the opinion wreaks as much havoc as its critics fear.

Had it truly wanted to issue a narrow ruling while reaching the same result, the majority should have held that the works in the Prince Series were indeed “transformative” in a legally relevant sense, having added “new expression, meaning, or message” to Goldsmith’s underlying photo; but then added that whether a work was “transformative” was not dispositive of fair use in general, or even of the first factor specifically. It could have done so while still signalling its agreement that fair use should not interfere with well-functioning markets for derivative uses. It could then either have resolved the fair use question itself, or remanded to the Second Circuit with instructions to reconsider the issue. Doing so would have helped preserve the Campbell framework while still helping to correct those courts that have erred in treating the “transformative” use inquiry as virtually dispositive.

[Appendix to the Court’s Opinion]

Pingback: Links for Week of June 23, 2023 – Cyberlaw Central()