“Private” Facebook Groups Aren’t Legally “Private”–Davis v. HDR

The plaintiff, Davis, is a member of two Facebook groups: “Ahwatukee411,” with over 32k members as alleged in the complaint (as the screenshot on the right shows, it’s now over 34k members), and “Protecting Arizona’s Resources & Children” (“PARC”), with 900+ members. Both groups are “private” Facebook groups:

The plaintiff, Davis, is a member of two Facebook groups: “Ahwatukee411,” with over 32k members as alleged in the complaint (as the screenshot on the right shows, it’s now over 34k members), and “Protecting Arizona’s Resources & Children” (“PARC”), with 900+ members. Both groups are “private” Facebook groups:

Both Ahwatukee411 and PARC have “always been” private, closed Facebook groups—meaning only group members can access and see posts made within the Groups. Both Groups require prospective members to undergo a screening process. Ahwatukee411’s screening process is “intended to ensure that only residents (i.e., those with a vested interest in the Ahwatukee community) can join the group.” The intent of PARC’s screening process is very similar: “to ensure that largely only residents (i.e., those whose homes would be affected by the construction of the local highway) can join the group.”

HDR offers “strategic communications” services to their clients, which includes monitoring and reporting on community sentiment/conversations about their projects. The plaintiff claims they “infiltrated” both of the Facebook groups to collect and analyze their conversations. The plaintiff sued HDR for ECPA and common law privacy violations. The court rejects both claims.

ECPA

The ECPA requires the plaintiff to show that “her posts in the Groups were not readily accessible by the general public.” Interpreting mostly pre-2010 cases, the court says that a new member’s self-certification of interest in the Facebook Group’s topics doesn’t really screen out the general public when “any person can become a member of the Groups, provided that they assert some unspecified level of involvement and interest in the community.”

Furthermore, the plaintiff didn’t have moderator power:

the Facebook posts at issue were not on Plaintiff’s own private Facebook wall such that she retained control over who could access and view them. Instead, Plaintiff’s posts were made in the Ahwatukee411 and PARC Facebook groups, forums over which Plaintiff had no control at all. Plaintiff had no authority over the Groups’ privacy settings and no voice in the screening process used to determine membership. Plaintiff therefore had no control over who was granted membership to the Groups and no ability to limit access to her posts to particular groups or individuals

Nevertheless, the plaintiff chose to make her posts to a “private” group, not to a public venue. The court says that’s irrelevant, because the group administrators could unilaterally change the privacy settings and allow the posts to become public. In a footnote, the court adds: “what is important for purposes of this analysis is not how the administrators have restricted access to the Groups to this point, but rather that Plaintiff has no say in the matter in the first place.”

Thus, the court summarizes:

The posts here would be considered “readily accessible” to the general public—and excluded from ECPA protection—because Plaintiff relinquished control over access to them when she posted in the Groups

The plaintiff pointed out that HDR gained access to the group on a false pretense (claiming to be interested in the topic, when really it was just a data snarfer). The court says that doesn’t matter either: “Defendant may very well have gained access to the Groups by misrepresenting its interest and involvement in the Ahwatukee community—or even by outright asserting that it was a Ahwatukee resident—but this does not necessarily mean that Defendant violated the ECPA if posts in the Group were not private, protected communications in the first place.”

Intrusion Into Seclusion

For similar reasons, the common law claim fails. The group was “readily accessible” to the public, so the plaintiff did not have any reasonable expectation of privacy in her posts (“Plaintiff relinquished any expectation of privacy in her online communications when she posted them in the Groups”).

Implications

What’s next? This is a rare case where I hope the plaintiffs appeal. While the court’s opinion is appropriately grounded in the precedent, it was tone-deaf to the privacy invasion. An appeals court might feel more free to stretch the precedent.

Group size doesn’t matter. I could have seen the court focusing on the group size. Is it realistic to call a conversation among 32k people “private”? Or even 900+? But this court swings in the other direction, suggesting that a conversation between only 2 people may not be protected by the ECPA or common law privacy when the speech venue is “readily accessible to the public,” even if others haven’t joined the conversation.

So when is a group “private”? The opinion doesn’t need to resolve when a group venue transitions from being “readily accessible to the general public” to “private.” It favorably cites the privacy controls in the 2-decade-old Konop case, where new members could join an online message board only if the system administrator had prepopulated their name on a membership list. While this certainly ought to qualify as a private group that isn’t readily accessible to the public, surely there are less restrictive approaches that still qualify as private?

So when is a group “private”? The opinion doesn’t need to resolve when a group venue transitions from being “readily accessible to the general public” to “private.” It favorably cites the privacy controls in the 2-decade-old Konop case, where new members could join an online message board only if the system administrator had prepopulated their name on a membership list. While this certainly ought to qualify as a private group that isn’t readily accessible to the public, surely there are less restrictive approaches that still qualify as private?

As I read the opinion, I kept thinking of Nextdoor, which allows anyone to join a local group if they authenticate their residency in the neighborhood. Where does this approach fall on the court’s spectrum? ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Remember the stakes here: the court says that an “infiltrator” can join a Facebook group under false pretenses and quietly surveil the “private” conversation and snarf anything they want–including the content of messages–with potentially no legal consequences.

So it seems like there ought to be some legal protections here. Maybe ECPA isn’t the right approach. Perhaps the false pretenses could give rise to claims not alleged in this case? (Breach of contract, perhaps? But that would only be enforceable by users in contract privity). Or perhaps Facebook or the group mods need to be the ECPA plaintiffs? (But Facebook’s content wasn’t snarfed, and the mods may not care as much as other users).

Is it false advertising for Facebook to describe the groups as “private”? Undoubtedly the plaintiff did not expect that a “private” Facebook group isn’t actually “private” at all. Does that create a claim for false advertising?

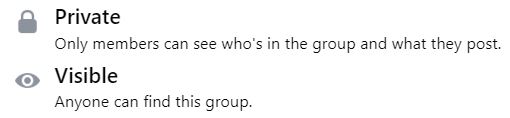

At minimum, if Facebook doesn’t abandon the “private group” descriptor (maybe “members-only” would be more accurate than “private”?), it might very well want to deploy more visible disclosures informing users what “private” means and doesn’t mean. Right now, in the group description, Facebook says:

This disclosure is fine so far as it goes, but it doesn’t provide any cautionary language to clarify that “members” could be the poster’s worst adversary without the poster realizing it, and the disclosures may need to be reiterated multiple places (not just on the group description page).

Case citation: Davis v. HDR, Inc., 2022 WL 2063231 (D. Ariz. June 8, 2022). The complaint.

UPDATE: The court dismissed the amended complaint. 2023 WL 399796 (D. Ariz. Jan. 25, 2023):

On the one hand, the Facebook groups were nominally private and had entry requirements that included a questionnaire asking for detailed information about the prospective member’s interest in the community. On the other hand, Plaintiff had no control over whom the administrators allowed into the groups, or whether they would change their entrance criteria at any point to be more or less stringent. The groups had vast membership (over 32,400 members in Ahwatukee411, and over 930 in PARC)…the current allegations appear to show that anyone, anywhere, with an internet connection and an interest in the community, could join the groups

The invasion of privacy claim gets the same response:

Plaintiff and other users should have been on notice that posting in a group with a large membership, even if nominally identified as private, was not a sphere of seclusion, but instead a forum where hundreds or thousands of people could interact based on entry criteria set by a third party that could change at any time.

UPDATE 2: A decision along the same lines:

the plaintiff argues that Sanchez’s comments were posted to a Facebook group designated as “private” by Facebook and are not connected to an issue of public interest. This Court disagrees. “Private” in the context of the Civil Rights Law is not the same as “private” as nomenclature used by the programmers who maintain Facebook. The fact that a Facebook group vets potential group members to ensure that individuals are earnest in their desire to engage with the public discourse being conducted and to help protect and empower the individuals participating does not render the group private and removed from the sphere of public interest. Therefore, this Court concludes that the Facebook group was a public forum for purposes of New York’s anti-SLAPP statute. Moreover, examining the content, form, and context of the statements, it is clear to this Court that the posts on Facebook are a matter of public concern for purposes of New York’s anti-SLAPP statute

Acosta v. Vann, 2024 WL 3035174 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. June 17, 2024)

Pingback: Facebook Moderator Defeats Defamation Lawsuit Over Termination Explanation-Margolies v. Rudolph - Technology & Marketing Law Blog()