Defendants Keep Getting Arbitration Despite the Anarchy in Online Contract Formation Doctrine

Online contract formation law has gotten strange. The proliferation of “wrap” variations has tied up judges in knots. Despite the increasingly baroque and incoherent legal doctrines, the bottom line has largely remained the same: most online contracts are properly formed under current doctrine and thus are likely to work in court. As evidence of that, I present three online contract formation cases that recently popped up in my alerts. The defendants successfully invoked arbitration clauses in all three:

Hosseini v. Upstart Network, Inc., 2020 WL 573126 (E.D. Va. Feb. 5, 2020)

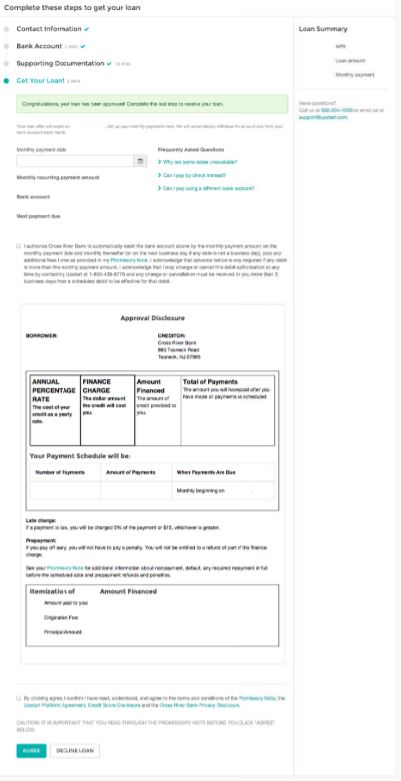

The plaintiff obtained an $18,000 loan in 2014 via the defendant, an online financial matchmaker. In 2016, he had the loan discharged in bankruptcy. He sued because the lender allegedly didn’t properly report the discharge. The matchmaker invoked the arbitration clause in its “Platform Agreement.” Here is the contract formation page:

If you can’t read that, here is a closeup of the page bottom:

The court calls this formation process a “hybrid clickwrap agreement” because the terms are hyperlinked and not displayed on the page. While the distinction between “clickwrap” and “hybrid clickwrap” agreements is a little disconcerting, the court says both are “routinely found to be valid, enforceable contracts,” citing Fteja v. Facebook. (So…why distinguish the two flavors?) Thus, the court says the arbitration provision is enforceable.

Not giving up, the plaintiff challenged the agreement’s authenticity. The defendant fought back with:

three declarations and several exhibits which defendant argues establish that plaintiff affirmatively agreed to the Platform Agreement and the arbitration clause contained within it. Anna Counselman, the Head of Operations and co-founder of defendant, averred in her affidavit that, at the time plaintiff applied for a loan in July 2014, the Upstart Platform “required him to accept” the Platform Agreement and other agreements “by affirmatively checking an ‘I Agree’ box or clicking an ‘I Agree’ button on the form.” Counselman also stated that “the prospective borrower cannot complete the loan application or use the Upstart Platform” without agreeing to the terms of the Platform Agreement and other agreements. Counselman reviewed defendant’s records and determined that plaintiff created his account and agreed to the Platform Agreement at 11:19 a.m. PST on July 10, 2014. The information included in Counselman’s affidavit is echoed by the declaration of defendant’s Head of Information Technology, Saikat Maiti. In a second declaration, Maiti provides a screenshot of the page depicting the “I Agree” box that appeared in July 2014 (through 2015)…Maiti states that the “I Agree” box provided a link to the Platform Agreement.

These declarations do the trick. “Defendant has provided undisputed testimony indicating not only that it was impossible to proceed to obtain a loan without agreeing to the Platform Agreement, but the exact time when such agreement took place.” Not every service can provide such a definitive time-stamp of contract formation for a specific individual, but it’s powerful evidence if available. The plaintiff argued that he never physically signed the agreement, which the court correctly says is irrelevant: “a physical manifestation of plaintiff’s signature seems even more unnecessary where defendant keeps a record of the date and time when plaintiff clicked the ‘Agree’ button and agreed to the Platform Agreement.”

Walker v. Neutron Holdings, Inc., 2020 WL 703268 (W.D. Texas Feb. 11, 2020)

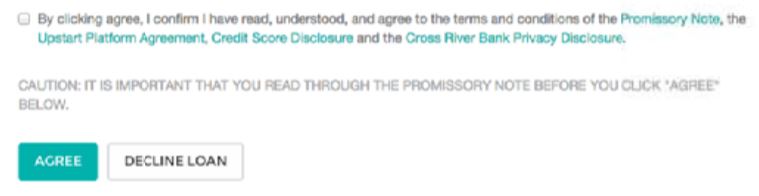

This is a Lime electric scooter case. The plaintiff claims the scooter had bad brakes, leading to physical injuries. Lime invoked its arbitration clause. Here’s the contract formation process:

I don’t love this presentation. First, the lime-green “next” button is at the very top, but there is visual separation between the “next” button and the purportedly binding legal text. This is similar to the “download now” exhortation that undermined Netscape’s SmartDownload contract formation in Specht v. Netscape. Second, if users look beyond the “next” button–which they have no reason to do–they could easily overlook the tiny grey font with the TOS call to action. It’s the smallest and faintest font on the screen. The plaintiff claimed (fairly IMO) “the text of the User Agreement notice is ‘small, faint, gray typeface, far below Lime’s invitation to ride,’ and is ‘practically illegible.'”

The court deems this a “sign-in wrap” (I can’t write those words without saying UGH). The court says sign-in wraps are enforceable “where the user had reasonable notice of the existence of the terms, i.e., where the notice was reasonably conspicuous,” evaluated by the standards of a reasonably prudent smartphone user (cite to Meyer v. Uber). After an uninspired recap of 5 cases, the court says conclusorily that “a reasonable user would view the Lime App signin screen and see that the User Agreement is part of the offer to proceed with the transaction by clicking ‘NEXT’ or ‘Continue with Facebook.'” Motion for arbitration granted.

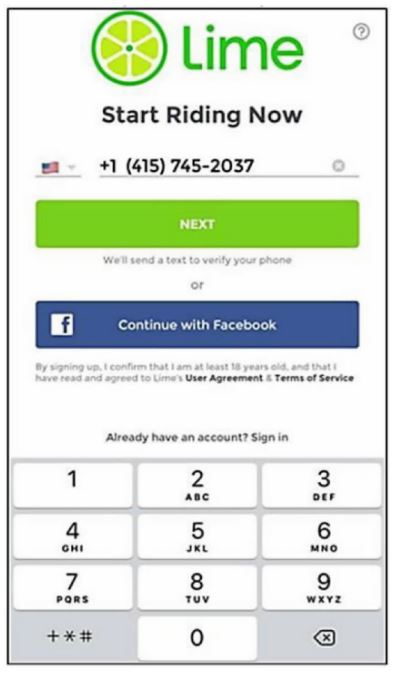

Troia v. Tinder, Inc., 2020 WL 619855 (E.D. Mo. Feb. 10, 2020)

This is an age discrimination lawsuit over Tinder Plus, which charges an extra fee to Tinder users over 30 years old. The plaintiff acknowledges agreeing to Tinder’s TOU. In a footnote, the court explains: “Tinder uses a sign-up wrap. Plaintiff consented to the TOU by tapping the Tinder Log In button directly below a disclosure that clearly explained that doing so constituted agreement to the TOU, which itself was accessible via a hyperlink in the disclosure.” While he acknowledged the standard TOU, he disputes agreeing to Tinder Plus’ TOU. The court says that the standard TOU arbitration clause incorporates his dispute over the Tinder Plus TOU.

Nevertheless, the plaintiff argued that the “hybridwrap” didn’t provide sufficient notice of the arbitration clause.

The court notes that the “terms” and “privacy policy” are hyperlinked, but this screen is so busy that the links required careful scrutiny to see the links. Nevertheless, the court concludes that “Troia was provided access to the TOU and accepted those terms, even if those terms were not presented on the same page as the acceptance button….The Court holds that this screen provides adequate notice under the case law that Troia would be bound by the TOU and the privacy policy.” Motion for arbitration granted.

The plaintiff’s unconscionability argument goes poorly. Troia worked for the plaintiff’s lawyer as a computer expert. “Troia created a Tinder account, subscribed to Tinder Plus less than two minutes later, and then filed this lawsuit on the same day. Troia admitted he specifically looked for arbitration agreements and TOU, but he does not dispute that he agreed to the TOU as part of his application for the Tinder service….given Troia’s clear knowledge of the TOU and prescience as to the arbitration agreement, the Court finds that this agreement is not unconscionable because there is no unfair surprise or oppression.”

The plaintiff has already appealed this ruling to the Eighth Circuit.

Want to Read More? A reminder that I’ve posted my entire Internet Law book chapter on online contracts for free download from SSRN. It covers all of the issues discussed in this blog post and much more.

Bonus Content: Kater v. Churchill Downs, Inc., C15-0612-RBL (W.D. Wash. Nov. 19, 2019).

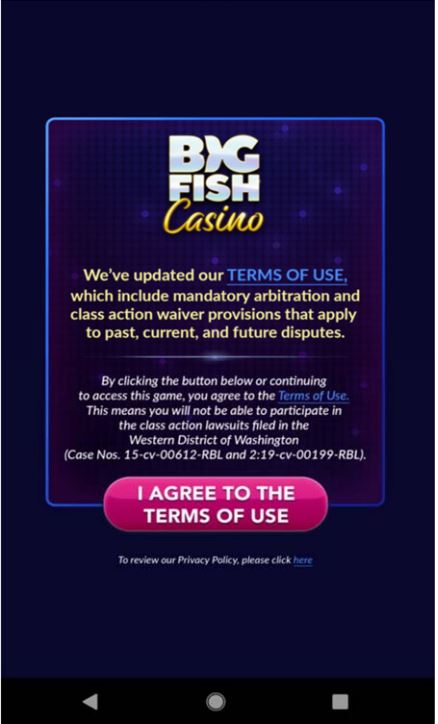

Sorry, this one got stuck in the blog queue. This case involves Big Fish Casino, no stranger to this blog. In what can only be described as a jerk move, Big Fish Casino nominally amended its TOU to expand its existing mandatory arbitration and class action waiver. The amendments expressly said they did not apply to the 3 named plaintiffs in a pending class action lawsuit. Everyone else could opt-out of the amendments by providing notice within 30 days. After posting the amended terms, Big Fish displayed this screen:

Can Big Fish get away with a stunt like this? Probably not:

Big Fish’s new pop-up, in conjunction with the revised Terms of Use, is coercive and misleading. The pop-up message presents putative class members with a stark choice: relinquish your class action rights and continue playing or maintain your rights and forfeit access to Big Fish’s games. This ultimatum is made more coercive by the addictive nature of Big Fish’s games and the fact that many players have already purchased chips that can only be accessed by agreeing to the terms. With such pressures at play, the pop-up, and revised Terms, are clearly intended to steer putative class members away from participating in these cases.

Nor is the coercive effect negated by the existence of an opt-out procedure. The pop-up window makes no mention of opting out; instead, it states very simply that clicking “I agree” and accessing the game precludes participation in a lawsuit. This seemingly binary choice gives users no reason to believe an opt-out provision exists somewhere in the Terms—indeed, as Plaintiffs point out, the word “mandatory” leads them to believe the opposite. The opt-out provision itself thus does not mitigate the coercion, and Big Fish’s attempt to hide the opt-out provision through a false ultimatum is misleading.

The court also said that Big Fish’s approach didn’t constitute proper communications with class members.

The court issued the following relief:

The existing pop-up is coercive and misleading as to those players who are putative class members in either lawsuit. Big Fish claims that some 90% of its players never buy chips. If it is feasible to do so, Big Fish may show a revised pop-up only to those players who have purchased chips during the relevant time periods and are therefore members of the putative class(es). The Court will not interfere with Big Fish’s communications with new players or old players who did not purchase chips in the relevant time frames. However, if Big Fish cannot find a way to separate its communications with putative class members from those with its general customers, Big Fish will have to abide by the following limitations in all pop-ups or whatever other method of communication regarding Terms that first reaches putative class members.

Any pop-up or other initial communication directed to putative class members must do the following. First, it must reference the ability to (and provide instruction on how to) OPT-OUT of arbitration and out of the agreement to WAIVE a player’s status as putative class member in either litigation. Second, it must briefly explain the rights at issue in these lawsuits such that an average user would understand what they are giving up by agreeing to the Terms. Finally, it must advise players to contact an attorney for advice on any of the legal terms and provide contact information for the Plaintiff’s attorneys with respect to the class action lawsuits. (Examples: “If you have questions about the legal effect of these provisions, you should contact an attorney.” “Plaintiffs in the putative class actions are represented by [Plaintiffs’ attorneys’ contact information].”).

Though not unprecedented, it was nice to see the judge acknowledge that virtual chips have value. We’ve long known that virtual items can have real-world economic value, but that doesn’t always translate into court.

Big Fish appealed the court’s order, but last week the Ninth Circuit dismissed the appeal for lack of jurisdiction.

Pingback: News of the Week; March 4, 2020 – Communications Law at Allard Hall()