A Fight for Authorship and Ownership of 150+ Quilt Patterns, and Bad Business Planning (Guest Blog Post)

by guest blogger Elizabeth Townsend Gard, Professor of Law (Tulane Law School); Lepage Faculty Fellow (A.B. Freeman School of Business); and host, Just Wanna Quilt podcast

Quilts are a little bit in the (copyright) news. What is a quilt? There are three parts to a quilt. The top, made many ways (patchwork, applique, whole cloth, to name a few); the batting (the fluffy part in the middle) and a backing. Once the top is completed, a quilter then puts the batting and backing together, and then “quilts” the pieces together. This case focuses on the patterns for creating the tops.

The art of quilting can be many things – art quilts, traditional quilts, to name a few. And the quilt can be based on traditional, long-known “blocks;” they can be improvisational; or in this case, based on a pattern created by designers. Quilters purchase the patterns because they like the way the top looks in the picture provided, or to learn a particular technique included with the pattern. Patterns sell for $5-20 for individual patterns, but they are also found in quilt magazines and publications specifically created within the quilting industry.

This case involves a terrible ending to a business that included two quilt designers: Lone Star Promotions v. Abbey Lane Quilts involves a business venture gone bad between Marcea Owen and Janice Liljenquist, who at the moment have three cases working its way through the courts. This is the second opinion on the district court case in Utah, the first from November 2018. The case concerns who owns the copyrights over 150 quilt pattern designs. The court called this a “tangled web of arguments with respect to their multiple claims against each other in three different courts” (3).

Quilting is a $5 billion industry, much of which is businesses typical of Abbey Lane Quilts. One or two (mostly women) come together to create and market patterns, which are sold in individually or in a book. Sometimes designers also create templates to go along with the books, which was true in this case as well. Quilters buy the patterns to make the quilts, bags, and other items for personal use. To be a successful, companies such as Abbey Lane Quilts participate in Quilt Market, a twice-a-year business convention put on by Quilts, Inc. They have a booth for quilt shops to see their patterns and quilts, and to connect with distributors, fabric companies and other designers. The pattern-making part of the quilting is competitive and challenging in making a living. And as this case demonstrates, partnerships are formed–often without thinking through the copyright authorship and ownership issues.

All of the facts are taken from two opinions so far rendered by the Utah district court. In 2007, Marcea Owen created the company Lone Star, whose primary business was web design services. A year later, Janice Liljenquist and Marcea decided to create a Florida at-will partnership, Abbey Lane Quilts, to sell quilt patterns and related products. Marcea created the website, and was “better at design and colors.” Janice was “better at sewing and pattern writing.” We are not sure exactly what this means, especially in terms of authorship.

The question was who owned the patterns, and who was the author when things went bad. Owen claims the patterns were made under her other company, Lone Star, and that Liljenquist made no copyrightable contribution, that in all but one, Lone Star (Owen) is the author, and finally that Lone Star had given an oral license to Abbey Lane Quilts to use the patterns.

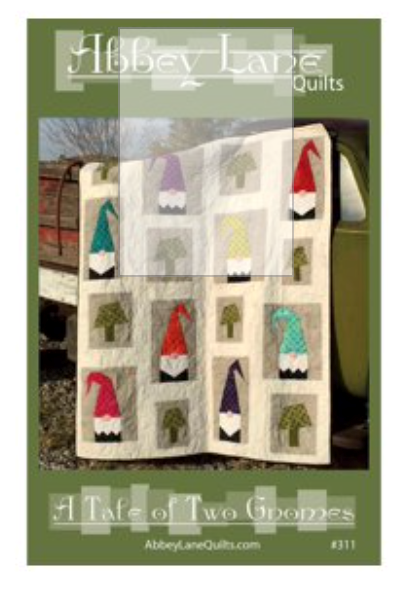

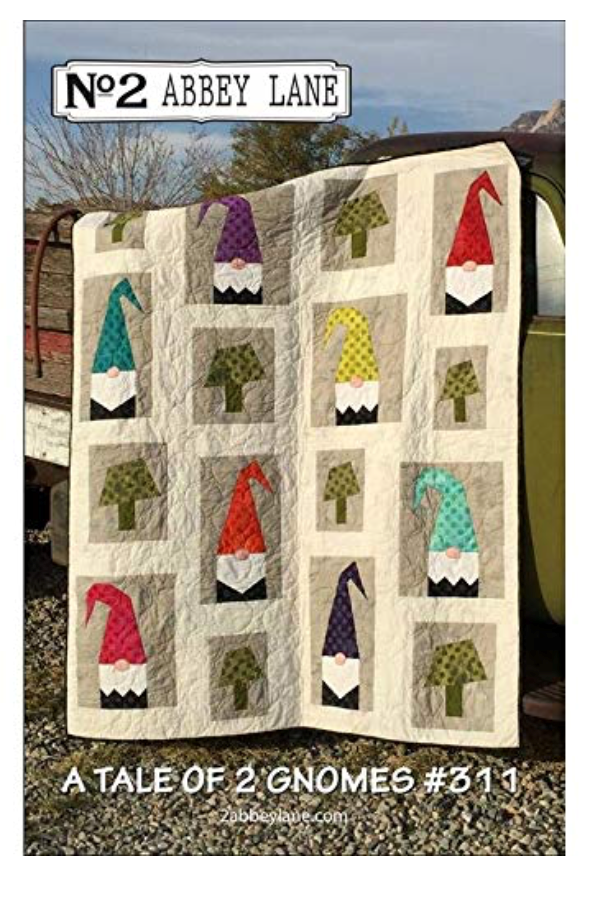

Liljenquist is also claiming joint authorship on the patterns, except for Tale of 2 Gnomes.

Liljenquist claims the patterns are collaborative, that it took both of them to come up with a pattern, and that the quilting world saw them as joint, collaborative designers. They were a team. Liljenquist denied that Lone Star had any control of the designs, that she never heard of an oral license from Lone Star, and that the tax returns for four years does not indicate any license agreement or royalty payments to Lone Star for such license.

It’s not clear from the court documents how the trouble began. On April 2, 2017, Liljenquist proposed to buy out Owen from Abbey Lane Quilts for $50,000 or, alternatively, end the company. Allegedly, Liljenquist had cancelled Abbey Lane Quilts credit cards, stopped selling products, refused to send samples or fulfill orders.

The story gets more confusing. Liljenquist created Abbey Lane Quilts, LLC in December 2016. And Owen made a yearly filing for Abbey Lane Quilts in 2017. Owen notified customers of Abbey Lane Quilts (the partnership) to communicate only with her, and Liljenquist notified Owen that she could not use any of the patterns without a payment of $50,000.

Then, Owen created a second business, 2 Abbey Lane, a Utah LLC. Such a mess! Owen said that she created new patterns under Lone Star, which were then licensed to 2 Abbey Lane to sell. These were all new designs, she contends. Owen reissued the “Take of 2 Gnomes” pattern under No 2 Abbey Lane. The ownership of this pattern appears to be the only thing the parties can agree upon, and is not subject of the case.

Owen reissued the “Take of 2 Gnomes” pattern under No 2 Abbey Lane. The ownership of this pattern appears to be the only thing the parties can agree upon, and is not subject of the case.

Then, in August 2017, Liljenquist and Abbey Lane Quilts, LLC filed a lawsuit in Utah for dissolution of Abbey Lane Quilts LLC by Owen. Liljenquist won a preliminary injunction against Owen as Abbey Lane Quilts LLC and 2 Abbey Lane from selling designs that had been sold under Abbey Lane Quilts partnership. Then, Owen filed a lawsuit against Liljenquist in Florida state court. “The Utah case has now been stayed pending resolution of the Florida case. The Florida case was then stayed pending resolution of this case.” (2) Both stays have recently been lifted.

The Utah state court granted a preliminary injunction in favor of Liljenquist and Abby Lane Quilts LLC, which barred Owen and 2 Abbey Lane from selling designs from the Abbey Lane Quilts partnership, and “Owens designs developed after Owen and Liljenquist had parted ways in April 2017 on grounds of alleged misappropriation of trade secrets and unfair competition.” Lone Star Promotions v. Abbey Lane Quilts, 2018 WL 5808802.

After that, Owen registered the copyrights in 8 designs. Before this registration, Abbey Lane Quilts had one copyright registration. Well, C&T Publishing, a large publisher of quilt and craft books, registered Baby Times: 24 Handmade Treasures for Baby & Mom as a book under the copyright claimant, Abbey Lane Quilts, listing a Florida address in 2012. Abbey Lane was listed as the author, and employer for hire. It appears to be the only registration filed by Abbey Lane Quilts.

In 2017, eight patterns were registered under Lone Star Promotions, as employer for hire, interestingly under a Florida address: Blossoms & Spokes, Notting Hill, Just Smashing, Manchester Square, Double Decker, Hyde Park, Chelsea Market, and Tale of 2 Gnomes. Lone Star Promotions is not a party to the state actions, even though Lone Star Promotions is the copyright claimant.

Then, the lawsuit in Utah district court was filed on June 28, 2018, and four months later, Lone Star filed the current motion for preliminary injunction against the Utah State Second District Court for allegedly violating 28 USC Section 1338(a) and improperly interfering with Lone Star’s rights under the Copyright Act. At the time of the state injunction, Lone Star had not registered its copyrights with the U.S. Copyright Office, and no copyright claims were in front of the state court, and in fact the preliminary injunction was based on trade secrets and unfair competition, not copyright. The “in aid of its jurisdiction exception to the Anti-Injunction Act also did not apply.

The court then turned to the preliminary injunction factors. As to likelihood of success on the merits, the court found significant disputed factors regarding authorship and licensing rights of the parties, and so there is no clear likelihood of success on the merits. Owen also stated the irreparable harm was her interference with her 106 rights under the Copyright Act, which she did not take up with the state court. Moreover, she could have had the case removed to federal court based on the federal trademark claim, and later the copyright registration. “The court cannot conclude that Lone State is irreparably harmed when it has not taken advantage of the procedures and remedies available to it.” Lone Star Promotions v. Abbey Lane Quilts, 2018 WL 5808802 (November 6, 2018). Also, over six months had passed since the state injunction, which lessens the optics that there is an immediate harm. Moreover, there are still opportunities to appeal and revise the preliminary injunction in state court. Therefore, the Utah district court denied the preliminary injunction against the Utah State District Court.

Motion to Dismiss in April: Which court?

The April 11, 2018, the Utah district court decision set out to resolve where the claims should be litigated: state or federal court. Defendant/Owen filed for a motion to dismiss, claiming that under Borden v. Katzman, 881 F.2d 1034 (11th cir. 1989), contractual disputes over copyright belong in state court.

Lone Star’s second amended complaint had claims of copyright infringement and a declaratory judgment on authorship. It is not clear just who owns the disputed 150 minus 1 pattern, and so Owen as Lone Star wanted the case to remain in federal court, as both copyright infringement as well as disputes over authorship are federal questions.

So many authorship questions: “whether Liljenquist is a joint author of that design who cannot infringe it, whether the lack of a writing is fatal to Lone Star’s copyright claim, whether the copyright was a work for hire, and whether the copyright is to the full pattern or just a picture of the design all go to the merits of Lone Star’s claims, not the jurisdiction of the court over those claims.” (3). It could get interesting! And more issues! The copyright registration of the patterns is not Owen’s name, and so the Defendant argues that Owen is not the proper Plaintiff.

The court did not dismiss for lack of federal subject matter or for abstention. Abstention was argued by the Defendants because there are other cases pending in state court. But the copyright issues must be resolved in federal court, and so the case was not dismissed.

My Take

This case is interesting on a number of levels. First, these kinds of disputes are throughout the quilting world, although they don’t often rise to three court cases. But this is a field with informal relationships, family businesses, and sometimes falling-out situations. Also, most of the pattern makers like Owen and Liljenquist do not register their works, as demonstrated by the records and timing on what Owen did register. The publishers, like C&T Publishing, regularly register their works, but even authors of published books by C&T do not register their individual patterns. (It is interesting that the original copyright was registered as Abbey Lane Quilts, of course). It’s just not part of the culture, even though they care so much about their patterns, as demonstrated by this case. Finally, the creatives in the quilting industry do not have much education on copyright, as demonstrated by the lack of clarity of ownership, authorship and other related copyright issues. Should this go all the way and we get a decision on ownership and authorship in these creative spaces that might help quilters, crafters and others better understand the importance of clear agreements, registration, and better attention to copyright issues.

To date, we do not have cases that discuss quilt ownership. The issues that arise are a bundle-ful. That’s what I’ve been working on for the last two years. Not only are there questions of authorship related to who created the quilt pattern, but most underlying patterns have significant elements in the public domain. Moreover, what is copyright protecting? Is it merely the image of the quilt? Is the math the image, or is it more like a recipe, and unprotectable? Then, there is the consumer side. When we buy patterns, are the pattern makers giving us a non-exclusive implied license to create the work (probably)? And derivative works (probably)? What about selling the completed works?

So, there are two paths that quilters ask questions on: ownership and how far their copyrights extend, even though they rarely register their patterns outside of a publisher registering a work, as in this case). And second, what can the average consumer do with the patterns–and how far do the rights extend to control the sale of the final products made by the general consumer. The second question is beyond the case, but is part of the larger “Just Wanna Quilt Copyright Study” at Tulane Law School. For more, also listen to the Just Wanna Quilt podcast, where we discuss copyright, quilting and other aspects of life, available at iTunes and other podcast venues.

Case Citation: Lone Star Productions, LLC v. Abbey Lane Quilts LLC, 2019 WL 1574804 (D. Utah April 11, 2019)