Copyright Owner Prevails in Lawsuit Over Form Contracts–Equine Legal v. Fireline Farms

The plaintiff is an Oregon law firm practicing equine law. The defendant runs a Florida horse ranch. In 2016, the defendant licensed the plaintiff’s “Equine Boarding Forms Package,” consisting of form releases for adults and minors. The license permitted the defendant to “copy, email and otherwise distribute the” forms but not post them to the web.

Starting in 2021, the defendant posted the forms to its website. There is some debate about whether the forms were actually linked from the website or were just dead-end URLs. Also, for unclear reasons, the defendant repeatedly kept uploading the files even after it previously removed the files in response to the plaintiff’s demands or pressure from upstream service providers who received the plaintiff’s DMCA notices. The plaintiff sued the defendant (and others) for copyright infringement.

Copyrightability

The case sets up one of the longstanding open questions in copyright law: when are form contracts copyrightable, and when is sharing them infringing? Sadly, this case sidesteps that important copyrightability question. The plaintiff had copyright registrations in the forms, and the defendant “ultimately concedes that plaintiff ‘has a valid copyright and a valid business in selling its copyrighted works.'” Due to that concession, questions about the copyrightability of form contracts will continue to fester.

Distribution

The court says “the Forms were accessible at the URLs that plaintiff located. As such, defendant made the Forms available.” However, the court says the plaintiff has to allege actual downloading, not just the mere possibility. The plaintiff didn’t provide any evidence supporting actual downloading, so this claim fails.

Public Display

The forms are “literary works.” Citing Bell v. Wilmott, the court says:

Like the plaintiff in Bell, plaintiff frequently conduct searches of the unique language it uses in the Forms to identify potential infringing uses. Plaintiff found the Forms on defendant’s website through these searches. It is undisputed that the Forms were accessible on defendant’s website, even if only temporarily. Even though it is likely that no other user would be able to find the Forms, by displaying the Forms on a webpage that was publicly accessible to anyone with an internet connection, defendant “publicly displayed” the Forms. This is true even though there is no evidence that any member of the public found or viewed the Forms, as plaintiff need not show any “minimum number of users who in fact accessed the [Forms through the website] to establish a prima facie case of infringement.”

So…the exact same facts that didn’t support a distribution will nevertheless support a public display…? Superficially, this makes sense because the distribution and display rights are different right and should not overlap. However, in practice, the defect with the distribution claim (no third person “got” it) applies equally to the display claim.

Defense: Express License

“Defendant’s argument that the terms of the License Agreement allowed particular kinds of distribution is unavailing because the provision unambiguously prohibits defendant’s exact conduct here—posting the Forms online.”

The court also rejects an implied license defense using an overly restrictive test.

Defense: First Sale Doctrine

The first sale doctrine is irrelevant because the court said the distribution right wasn’t infringed. Also, there’s no digital first sale right, but the court doesn’t reach that issue.

Defense: DMCA Online Safe Harbor

“defendant caused the Forms to be made available online; it was not merely an entity that facilitated transmission of the Forms.” (The court also bizarrely says in a single sentence that the defendant isn’t a service provider, which is surely incorrect because the definition is a “provider of online services”).

Also curious: the court doesn’t discuss a fair use defense at all.

Statutory Damages

The plaintiff asked for $75k in statutory damages. The defendant argued for only $400 in statutory damages (“equal to two innocent infringements”).

With respect to willfulness, the court addresses the defendant’s repeated reuploads of the forms to its website:

plaintiff identifies six instances in which the Forms were accessible on defendant’s website, and defendant does not dispute that these instances occurred. It is also undisputed that defendant received five DMCA notices relating to the Forms. However, no evidence in the record shows that defendant was aware that the Forms were publicly accessible on its website before it received the DMCA notices. In fact, the evidence shows only that after defendant received each of the DMCA notices, either directly from plaintiff or through its ISP, defendant worked to have the Forms removed from the website and cease the infringing conduct

This is about the gentlest possible way a court could characterize the defendant’s repeated reuploads. I imagine many judges would have been less sanguine about the defendant’s mistakes/sloppy practices. In any event, the court concludes there’s no evidence of willful infringement.

The court doesn’t explain how the defendant’s infringement could be characterized as “innocent” infringement. For example, 17 USC 401(d) says the innocent infringement doctrine isn’t available when the work displayed a copyright notice, which I have to assume was the case with the forms at issue given how carefully the plaintiff handled its IP management.

Despite the likely unavailability of the innocent infringement doctrine, the court agrees with the defendant and awards the plaintiff only $400 of statutory damages. (Without the innocent infringement doctrine, the damages should have been at least $1,500). Such a paltry award is a major loss for the plaintiff, because $400 in damages surely doesn’t justify the time and cost of enforcement. However, the court also says that the plaintiff can get its costs and attorneys’ fees, which will dwarf the damages. Will the attorneys’ fee shift be enough to make this case worthwhile to the plaintiff?

Case Citation: Equine Legal Solutions PC v. Fireline Farms, Inc., 2025 WL 485493 (D. Ore. Feb. 12, 2025)

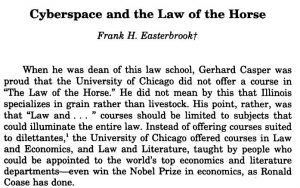

Want more about the Internet law of horses? Check out this old battle between the virtual horses and the virtual bunnies.