Another “Sign-in-Wrap” TOS Formation Process Fails–Morrison v. Yippee

When properly implemented, “sign-in-wraps” support TOS formation. Unfortunately, some websites make dubious choices in their implementation, even though the protocols for proper formation seem so simple to me. Courts are also struggling with how to compare “sign-in-wraps” to “clickwraps,” which are treated the gold standard of formation processes. Today’s ruling shows how these dynamics combined to doom what many Internet contract lawyers would have thought was a suboptimal but effective formation process.

* * *

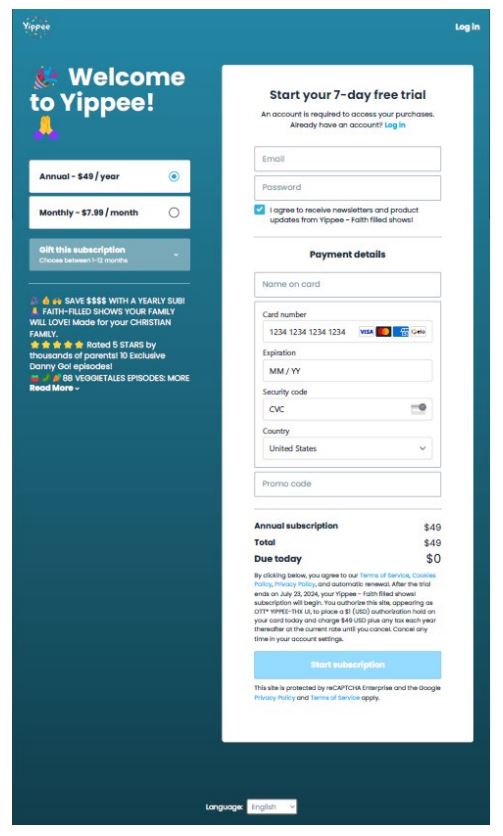

This is a VPPA case against Yippee TV, “a faith-based video streaming service.” Yippee invoked arbitration per its TOS, so it had to establish that it properly formed its TOS. Yippee subscribers had to navigate this screen:

There’s a lot going on with this screen (so many emojis!), and no doubt it could have been improved. The key areas are the light blue “start subscription” button near the screen bottom, as well as the paragraph above it, especially the first sentence. Confusingly, the paragraph below the button also has TOS and privacy policy links related to the reCAPTCHA, which the court notes.

The court correctly categorizes this implementation as a “sign-in-wrap” (ugh). The court then says “sign-in wrap agreements…fall somewhere between browsewrap, which courts are reluctant to enforce, and clickwrap, which courts routinely enforce.” Notice what the court did here: instead of treating sign-in-wraps as nearly as enforceable as clickwraps, the court implicitly characterized sign-in-wraps as somewhere in the middle of the spectrum. The court’s statement is technically correct, but it gives a misleading impression that sign-in-wraps are not “routinely enforced”–even though they are. This means the court gives less deference to the sign-in-wrap formation process than it should have.

The court says that “a consumer would anticipate at least a limited ongoing relationship based upon their subscription” with Yippee. This counsels in favor of TOS formation.

Nevertheless, Yippee didn’t provide sufficient notice of the TOS:

While the “Terms of Service” hyperlink appears in blue font against a white background—a characteristic to which many courts look—the font is not underlined nor completely capitalized and is small in proportion to most of the text on the page. Likewise, the “Terms of Service” hyperlink comes in a sequence of three hyperlinks (albeit separated by black-font commas), and it is not immediately clear whether these lead to different, or the same, webpages. Further, though located near the “Start Subscription” button, it is within an eight-line paragraph, all in font smaller than that on the page generally. Additionally, the page contains promotional material displaying emoticon illustrations and self-promotional statements, which draw a viewer’s attention away from the hyperlink. Finally, this webpage contains a second hyperlink labeled “Terms of Service” below the “Start Subscription” button. While the text above this hyperlink informs the user that it redirects them to Google’s terms of service—which apparently also apply—a second hyperlink with the same name and similar placement as the one in question only further draws the viewer’s attention and may cause confusion

Later, the court distinguishes some cases finding sign-in-wrap TOS formation because “unlike here, hyperlinks generally appear on simple, uncluttered webpages, in text of one sentence or little more, with few, if any, additional hyperlinks around them.” While TOS call-to-actions should have ample defensible space, the court overstates the matter by saying that generally the entire web pages are “simple” and “uncluttered.” That’s not a specific requirement of TOS formation; the test is whether consumers would have seen and understood the call-to-action. I think the court’s interpolating sign-in-wraps between browsewraps and clickwraps caused the court to shift the formation standards.

Undisputably, Yippee can and should have implemented its TOS formation better, even if had chose not to deploy a two-click process (which could have easily done–note the pre-checked opt-out for marketing emails near the top of the screen). Bigger fonts. More defensible space. Underline the links. Get rid of the reCAPTCHA TOS or make it sufficiently visually distinct that it’s not distracting from the main call-to-action. Fix the call-to-action to tie to the action button’s language. These are all trivially easy steps. Despite that, I still think that most lawyers would have considered this implementation as highly likely to be enforceable, and it wouldn’t surprise me if an a appellate court reaches a different conclusion.

I recently blogged the Kuhk case, another failed sign-in-wrap formation process. From a defense standpoint, both rulings are bummers because they were so easily avoided. Sign-in-wraps are enforceable; the websites just need to adhere to best practices of TOS formation.

Case Citation: Morrison v. Yippee Ent., Inc., 2024 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 19855 (S.D. Cal. Oct. 31, 2024)

* * *

UPDATE: In a major upset, the Ninth Circuit reverses this ruling. It explains:

Here, the hyperlink appeared in bright blue font against a clean white background that stood out from the surrounding text to indicate it was clickable. The hyperlink was also located directly above the “Start subscription” button—precisely where a user would expect it within the natural visual path of completing the subscription process—and alongside the statement that, “[b]y clicking below, you agree to our Terms of Service.” The format of Yippee’s webpage was also not so visually cluttered that it distracted from the hyperlink, and the presence of other hyperlinks or placement within a multi-line paragraph did not negate its conspicuousness. Because we “can fairly assume that a reasonably prudent Internet user would have seen [the hyperlink]” based on these features, there was reasonable notice.

In addition to these visual features, the “context of the transaction” further demonstrates that the Terms were reasonably conspicuous. A reasonable user subscribing to Yippee’s recurring streaming service would have “contemplate[d] some sort of continuing relationship” that prompted scrutiny of the website for any contractual obligations or terms.

Chabolla gets a couple of nods. The panel doesn’t cite the Godun opinion at all. I think it would be virtually impossible to distinguish these screenshots from the Godun screenshots. Maybe the transaction context was enough to swing it? Based on the composition of the panel, it might also be that Morrison got an unlucky draw, which makes me think the Ninth Circuit cannot develop or apply consistent rules.

Morrison v. Yippee Entertainment, Inc., No. 24-7235 (9th Cir. August 18, 2025)