More Evidence That IP Law Protects Individual Emoji Depictions–Nirvana v. Marc Jacobs

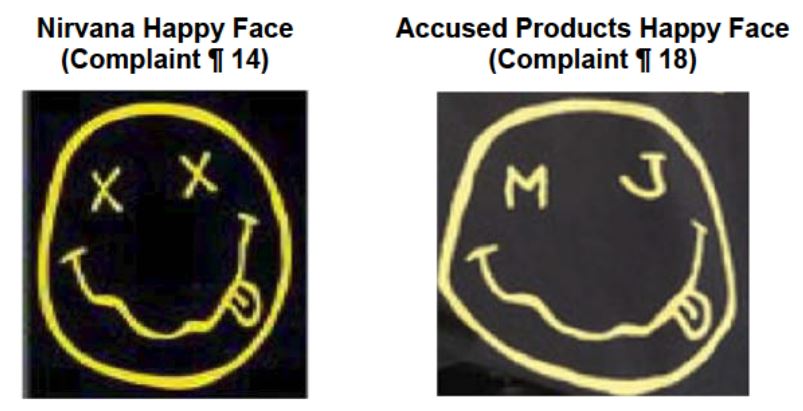

This case involves the well-known “Nirvana Happy Face” drawn by Kurt Cobain in 1991 and registered in 1993. Marc Jacobs launched a “Bootleg Redux Grunge” clothing line (really??? who buys this shit?) that included an homage to the Nirvana Happy Face depicted below.

Nirvana sued for copyright and trademark infringement and more. The court’s ruling covers a lot of ground, but I’ll highlight the copyrightability/trademarkability and infringement analyses.

Copyright. The court says that the Nirvana Happy Face is copyrightable because:

The similarities between the two faces include: (i) “[t]he slightly asymmetrical circle shape of the face”; (ii) “the relatively wide placement of the eyes”; (iii) “the distinctive ‘squiggle’ of the mouth”; and (iv) “the placement and use of a ‘stuck out’ tongue in the same shape on the same side of the mouth.” These features distinguish the Happy Face from the generic idea of a smiling face.

As you can see, the Marc Jacobs depiction is similar to the Nirvana version. The main differences is that the Marc Jacobs’ version is a little less circular and more oval than the original; and the Xs-for-eyes are replaced with the letters “M” and “J” (I assume for Marc Jacobs, but maybe it’s for Mary Jane?). The court says these differences are not enough to grant a motion to dismiss.

Trademark. The court similarly cannot reject a trademark infringement claim:

The Complaint sufficiently alleges likelihood of confusion as to the source of the Accused Products. It alleges that the Accused Products use a “virtually identical copy” of the design and logo that Nirvana has used on its “services and merchandise” for more than 25 years. It alleges that the Accused Products are similar to Nirvana’s, including t-shirts and sweatshirts. As described above with respect to the copyright claims, the allegations and images are sufficient to show substantial similarity. For similar reasons, it is plausible, based on these similarities, that a factfinder would find in favor of Nirvana as to whether the “consuming public” would incorrectly assume “that all goods or services that bear the logo are endorsed by or associated with Nirvana.”

Implications. The Nirvana Happy Face is a smiley, not an emoji, but I think most of the analysis would apply equally in most cases. (The primary difference is that an ordinary emoji might not have any use in commerce to qualify for trademark protection, but we’d have to see if it had been merchandised). This ruling can support the following two propositions:

1) a face emoji could be eligible for copyright protection if it has enough distinguishing details, and

2) a variation of a copyrightable/trademarkable face emoji will need more than minor deviations to avoid infringement; otherwise courts will consider it “substantially similar.”

I posited both propositions in my Emojis and the Law paper, so I don’t think this outcome is surprising. Still, it’s unsettling to see a clear example of how individual emoji depictions should qualify for copyright and trademark protection (some of my papers’ arguments were by analogy). Rulings like this reinforce why I think emoji designers continue to add minor and unnecessary variations to their platforms’ depiction of Unicode emojis–when those details creates avoidable and potentially tragic misunderstandings when emojis travel across platforms. To prevent this, we should reconsider how basic copyright and trademark law applies to individual emojis.

Case citation: Nirvana, LLC v. Mark [sic] Jacobs International, LLC, LA CV18-10743 JAK (SKx) (C.D. Cal. Nov. 8, 2019)