Maternity Clothing Trademark Dispute Has Dubious Support–Blanqi v. Bao Bei (Guest Blog Post)

by guest blogger Alexandra J. Roberts

This one’s for the ladiesss (all the pregnant ladies, all the pregnant ladies)!

Plaintiff Blanqi makes high-end shapewear and maternity products. It has a pending application to register SPORTSUPPORT as a trademark for lingerie and other apparel based on its intent to use the mark in the future (“ITU”). That ITU application was published back in 2015, suggesting that the USPTO attorney who examined it considered the mark inherently distinctive for the goods listed. Although Blanqi recently filed its fourth request for extension of time to submit its statement of use to the USPTO, it claims common law trademark rights in SPORTSUPPORT based on use in commerce to market sports bras and tank tops.

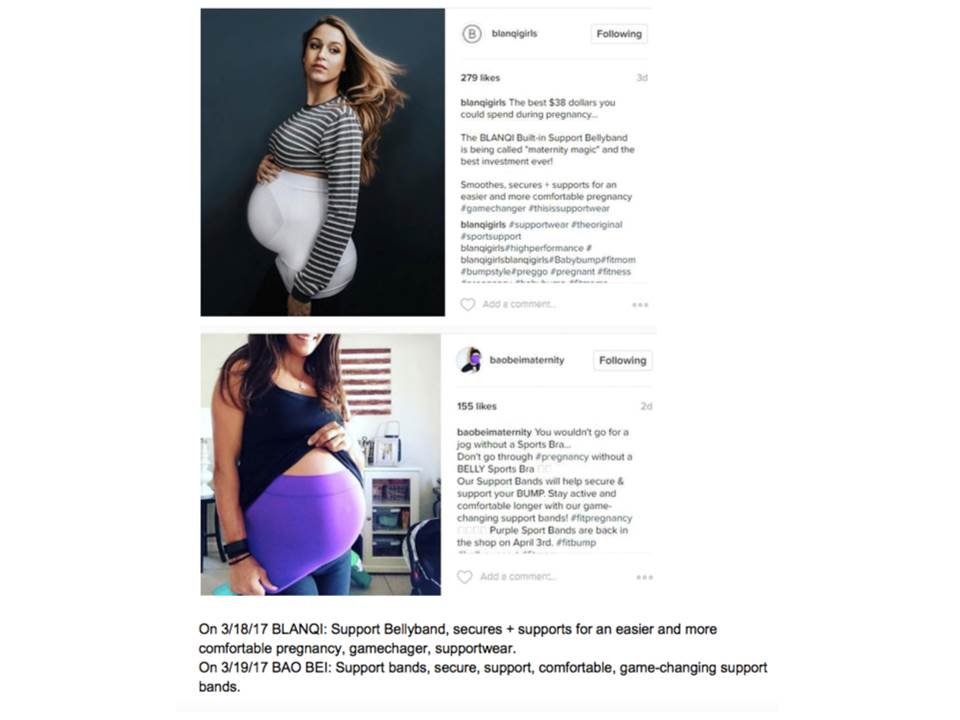

Defendant Bao Bei Maternity also sells supportive maternity wear. Blanqi alleges that Bao Bei infringed and continues to infringe its trademark rights in SPORTSUPPORT by marketing a sports bra on Instagram “in connection with the trademark SPORTY SUPPORT.” (Blanqi’s exhibits don’t include any evidence of its use of SPORTSUPPORT or Bao Bei’s use of SPORTY SUPPORT.) Blanqi further alleges that Bao Bei copied various elements of its social media ad campaign, namely “original text and the overall appearance, including color schemes, fonts, and the general layout and style, created by Blanqi on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, and Blanqi’s company website.” It appends examples:

Blanqi asserts two causes of action in N.D. Cal., one under section 43(a) of the Lanham Act based on Bao Bei’s use of “sporty support” and the second under California’s unfair competition statute based on that and the copycat social media posts. The Lanham Act claim is not styled clearly as either a claim of common law trademark infringement or a claim of false designation of origin. While pleading purity is not necessary at this stage in the proceedings (or perhaps ever), that lack of clarity makes it harder to determine the right analysis.

Bao Bei moved for judgment on the pleadings, which the court denied, resulting in its February order.

SPORTSUPPORT

Bao Bei defends the Lanham Act claim on the grounds that its use of “sporty support” just two times, once in 2016 and once in 2017, is de minimis and constitutes classic fair use: it claims it used “sporty support” descriptively, in good faith, and other than as a mark. The court sidesteps the question by holding that fair use is an affirmative defense better left for summary judgment. But its brief analysis blurs the distinction between a common law trademark infringement claim and a 43(a) false designation claim, just as Blanqi’s complaint does.

In order to make out a successful claim for infringement of a registered or unregistered trademark, Blanqi would have to own and use in interstate commerce a valid, distinctive trademark. As Bao Bei correctly argues, a pending ITU application is not a valid trademark and cannot provide the basis for an infringement claim (although once trademark rights accrue, the ITU application can be useful in establishing priority). While it’s probably inappropriate to draw a negative inference from the fact that the company chose to file an ITU rather than a use-based application, and has yet to perfect that application, the application’s mere existence doesn’t carry much weight in a cause of action for infringement. Common law rights may form the basis for an infringement claim, and the fact that Blanqi alleges it possesses them is all the court needs to deny the motion at this stage of the litigation. But Bao Bei alleges—and internet searches and a review of Blanqi’s website seem to confirm—that Blanqi barely uses SPORTSUPPORT at all, let alone as a trademark, which might be why it continues to seek extensions of time to file a statement of use and supporting (pun intended) specimens. What’s more, even though the USPTO treated it as inherently distinctive, the mark is arguably merely descriptive—“sport support” for sporty, supportive garments seems flatly descriptive, and combining the two words into one doesn’t create a double entendre or require enough use of imagination to render it suggestive. (it wouldn’t be the first time the USPTO found rhyming marks suggestive rather than descriptive, though: see TTAB decisions on AIR CARE; ACTION SLACKS; BEST REST; and STRIPE WRITER.) Based on its borderline distinctiveness and its minimal use, SPORTSUPPORT might not stand up to a validity challenge at trial. Even if it were found to be protectable, it’s a weak mark at best, and because of Blanqi’s minimal use the mark lacks acquired distinctiveness to bolster its strength.

That may be why Blanqi (kind of) styled the claim as one for 43(a) false designation, rather than common law trademark infringement, even while reciting its trademark rights. A 43(a) false designation claim does not technically require valid trademark rights. So even if Bao Bei is correct in arguing that Blanqi hasn’t begun using the mark in commerce, Blanqi could theoretically still make out a successful false designation of origin claim if it can establish that Bao Bei uses “sporty support” in a way that creates a likelihood of consumer confusion with Blanqi.

43(a) false designation of origin claims come in a few varieties, and they’re not always cleanly delineated by litigants or courts. If Blanqi can’t prevail on a common law infringement-based 43(a) claim because it doesn’t own and use a valid trademark, its best bet is probably the trademark-adjacent variety—a claim that Bao Bei is still somehow creating a false association or likelihood of confusion with Blanqi by using the phrase “sporty support.” But that theory too seems far-fetched on these facts. 43(a) can act as a safety valve in those situations where consumers are likely to be deceived even though technical trademark protection is unavailable. The types of plaintiffs who might succeed under a trademark-adjacent theory include users of generic terms and phrases (Shredded Wheat; Blinded Veterans Association); owners of foreign marks whose reputation reaches some US consumers even without US use (Grupo Gigante; Flanax); creators of marks in fictional universes with which consumers have strong associations even though the marks have not actually been used in commerce with real goods or services (Krusty Krab; Kryptonite; Sabacc); and marks that are the subject of substantial pre-sale publicity campaigns and media attention (think iPhone after Jobs’ 2007 announcement but before it was available for sale). In all of those scenarios, the 43(a) plaintiff possesses reputational rights significant enough that a defendant’s use of similar matter has the capacity to deceive or confuse. Here, plaintiff and defendant each make minimal use of minimally protectable phrases. We can reasonably expect that the same things that keep the plaintiff from establishing trademark rights—the mark’s descriptiveness, the paucity of use, the type of use—will keep it from making out a successful false designation claim.

Instagram Promotions

As for the copycat advertising, a similar analysis applies. Despite its allegations about its ads’ “original appearance, including color schemes, fonts, and general layout and style,” Blanqi’s posts don’t seem to use or allege distinctive enough elements to support an assertion of protectable trade dress. Both companies’ posts on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter look like standard social media posts; both use the kind of stock photos of active pregnant women and generic language about motherhood that dominate ads in the industry. Taken side by side as they’re presented in the complaint, the language and themes of the two companies’ social media posts may arouse suspicion that the similarities are more than coincidental. But if consumers don’t associate the style or substance of Blanqi’s posts with the company or its products, Bao Bei’s similar posts are unlikely to deceive or mislead anyone.

All that said, the court’s denial of Bao Bei’s request for judgment on the pleadings is not surprising given Blanqi alleges common law trademark rights and the court must take the facts alleged as true. But Blanqi’s factual claims seem to lack, ahem, support. Navigating the onslaught of social media advertising without confusion is just #momlife.

Eric’s Comments:

* It’s a liberal application of pleading rules to let a plaintiff’s complaint proceed when it didn’t “include any evidence of its use of SPORTSUPPORT or Bao Bei’s use of SPORTY SUPPORT.”

* I have repeatedly raised policy concerns about trademark fair use as an affirmative defense, because it’s hard for defendants to defeat bogus claims early. “SPORTY SUPPORT” for maternity athleticwear sounds like an easy case for descriptive fair use. Especially in light of the plaintiff’s minimal use of the SPORTSUPPORT term, the court should have required more specific pleading or axed the case now.

* The similarity of the Instagram promotions seemed mockable. No matter how much inspiration Bao Bei drew from Blanqi, treating “it’s designed for bodies that motherhood made” as legally equivalent to “They are made for #momlife” undermines the plaintiff’s credibility to me.

Case citation: Blanqi, LLC v. Bao Bei Maternity, 2018 WL 905908 (N.D. Cal. Feb. 15, 2018)