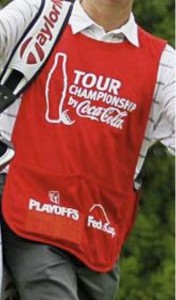

PGA Can Turn Caddies Into ‘Human Billboards’–Hicks v. PGA Tour

As I’ve written before, marketers are in a never-ending quest to find and exploit new ways to capture consumer attention. With the rise of DVR ad-avoidance technologies, marketers keep finding more unskippable broadcast TV ad exposures like product placements. And in live sports events, seemingly every surface in a sports venue has become a tabla rasa for more ads.

The judge starts by contextualizes golfing tradition. In a variation of “coming to the nuisance” arguments, Judge Chhabria explains that “caddies have been required to wear the bibs for decades,” “wearing a bib during tournaments is part of the job,” and “the bib is the primary part of a caddie’s uniform.” With that backdrop, the judge shreds the caddies’ attempts to find a legal doctrine to fit their gripes:

Breach of Contract: the caddies argued that their contract with PGA didn’t expressly require them to wear ad-laden bibs. The contract’s key sentence says: “Caddies shall wear uniforms and identification badges as prescribed by the host tournament and PGA TOUR.” The court says “no reasonable person signing the contract after 2010 could believe he retained the right not to wear a bib during a tournament,” thus resolving the contract claim. The caddies argued economic duress–a bizarre and seemingly desperate argument–but the court responds that the caddies never made money from selling logo endorsements for their bibs, so they aren’t losing any money they once had.

Publicity Rights: I thought this was potentially the most interesting claim because the caddies “allege the Tour is violating their ‘right of publicity’ by using them as ‘human billboards.'” The court says the caddies consented to wearing the bibs via their contracts, plus the contract separately assigned the caddies’ “media rights” (whatever those are) to the PGA. For the same reason, the Lanham Act false endorsement claim fails.

Antitrust: I didn’t really understand the caddies’ alleged prima facie antitrust violations, but the court crushes it anyway:

Companies that wish to advertise things like golf balls or luxury watches to fans of pro golf can do so in a variety of ways: television ads, magazine ads, internet ads, posters at golf course clubhouses, and more. To be sure, not all forms of advertising are the same, and some forms have benefits that others don’t. For example, with a television ad, a company can communicate a detailed verbal and visual message about its product (including but not limited to an endorsement by a golfer, or an actor, or a caddie, or some other figure). With a magazine ad, the company cannot communicate verbally, but it can communicate visually, and the ad might be hard to ignore if it appears on the page opposite an article someone is reading. With a logo being worn by a caddie or a golfer during a tournament, the company’s communication capabilities are far more limited, but perhaps the communication is more likely to catch someone’s eye. However, it’s not enough to allege that these forms of advertising have differences….To implicate the antitrust laws, the caddies must allege facts from which one could plausibly conclude that these different methods of advertising to golf fans are not reasonably interchangeable, such that even if the price of one advertising method went up in a meaningful way, companies would not switch to another method of advertising. The caddies have alleged no such facts. Even assuming the caddies are correct that an endorsement of a product by a golfer or caddie is sufficiently different from an advertisement without an endorsement, the endorsement market cannot be so narrowly defined as to include only in-play endorsements and not also endorsements communicated via other media, because it isn’t plausible that an increase in the price of in-play endorsements would have no effect on the demand for other types of endorsements, or vice versa. Likewise, with respect to the live action advertising market, while it may be true that the advent of DVRs has rendered in-play advertisement opportunities more attractive than they previously were, it does not plausibly follow that a price increase in in-play advertisement opportunities would have no effect on the demand for other forms of advertisement to golf fans. If it became too expensive to put a logo on a bridge, there is no logical reason a company wouldn’t decide instead to put its logo on a magazine ad, or on a wall in golf course clubhouses, or any number of other places.

This vaguely reminded me of this post: Free-to-Consumers Ad-Supported Website Isn’t Illegally Priced–Cammarata v. Bright Imperial.

Conclusion: The court concludes: “The caddies’ overall complaint about poor treatment by the Tour has merit, but this federal lawsuit about bibs does not.” In other words, the caddies get no more love in court than they get from PGA.

Implications

I can distinguish this ruling from other publicity rights situations where a plaintiff’s arguments might have more traction. First, employers ordinarily can’t use employees in advertisements without additional or separate consent. In contrast, the caddies’ contract (and the very nature of the job) clearly contemplates significant public exposure, and the court’s references to tradition further suggest that caddies are a special class of employment. This case is also different from the situations where video footage is captured for editorial purposes but then used for advertising purposes. In those situations, even a well-drafted consent may not permit that secondary usage. Partially related: “Breastfeeding Mom Can Sue Video Producer Despite Signing a Blanket Release–Sahoury v. Meredith.” In this case, there was no “bait-and-switch” by the PGA. The caddies are being forced to wear ad-laden bibs, not having their images recycled in unexpected places.

More generally, this case is part of the macro-trend of turning regular people into unwitting marketers. See, e.g., Facebook Sponsored Stories. As the case illustrates, with the right contract language, pretty much anything is fair game. Cf. Lawsuit From Huffington Post Unpaid Contributors Gets the Boot – Tasini v. AOL.

In this case, it’s hard to know if we should feel truly sorry for the caddies. If the caddies’ overall compensation is predicated (directly or indirectly) on some of the revenues derived from the bib ads, they may be getting a fair economic deal even if they don’t see a separate line item for the bib logos. Even if the golfers, not the PGA, pay the caddies, the golfers’ revenues derive in part from the PGA’s payouts that may be enhanced by the bib ads. The quid-pro-quo justification can be harder to see in situations with free services like Facebook’s sponsored stories; and the harder it is for us to understand the quid-pro-quo, the more exploitative it feels, irrespective of what the contract says.

Other related posts: “Tattoo Advertising/Human Billboards,” “Getting Paid to Drive an Ad-wrapped Car” and “Infomediaries–Where Are They?” This ruling also brought to mind the recent Google CAPTCHA ruling. Not every spillover must be fully internalized!

Case citation: Hicks v. PGA Tour, Inc., 2016 WL 928728 (N.D. Cal. Feb. 9, 2016)