Court Denies Preliminary Injunction Against Minnesota’s Anti-“Deepfakes” Law–Kohls v. Ellison

“Minnesota Statutes section 609.771 prohibits, under certain circumstances, the

dissemination of ‘deepfakes’ with the intent to injure a political candidate or influence the result of an election.” The plaintiffs brought a pre-enforcement challenge to the law, but the court denies a preliminary injunction.

What is a “Deepfake”?

The court explains:

Deepfakes are image, audio, or video files that mimic real or nonexistent people saying and doing things that never happened. Deepfakes leverage artificial intelligence (“AI”) algorithms to manipulate digital content—ordinarily images, sounds, and videos—in which a person’s likeness, voice, or actions are convincingly altered or fabricated. The AI technology behind deepfakes is advanced and complex, making it difficult for the average person to detect the falsity of a deepfake.

According to Wikipedia, deepfakes is a portmanteau of “deep learning” and “fake,” but I find the term nonsensical. When does a fake become a deepfake? I prefer the term “inauthentic” content or just “fake” content (leave the “deep” out of it).

Standing

The plaintiffs are Christopher Kohls a/k/a Mr. Reagan, who uses AI tools to create right-wing propaganda content, and Rep. Mary Franson, who enthusiastically and unapologetically shares such propaganda.

The court says the statute “does not penalize pure parody or satire….the statute at issue here only proscribes a deepfake insofar as it ‘is so realistic that a reasonable person would believe it depicts speech or conduct of an individual who did not in fact engage in such speech or conduct.'”

Hmm. The court does realize the overlap here, right? That sometimes the joke is the absurdity of the putative speaker saying it?

The court says Kohls’ content at issue qualifies as constitutionally-protected parody:

the July 26 and August 9 Videos that Kohls posted were labeled as “PARODY” and included a disclaimer that “Sound or visuals were significantly edited or digitally generated.” It also appears that Kohls regularly includes the term “PARODY” in the titles of other videos that he has published, along with a disclaimer that “Sound or visuals were significantly edited or digitally generated.” Given Kohls’s repeated disclaimers that his deepfake videos are “PARODY” and that “[s]ound or visuals [are] significantly edited or digitally generated,” the Court concludes that no reasonable person would believe his dissemination of the July 26 and August 9 Videos depict “speech or conduct of an individual who did not in fact engage in such speech or conduct.” Indeed, by labeling his videos as “PARODY,” Kohls is announcing to his viewers that the videos “cannot reasonably be interpreted as stating actual facts about an individual.”

This is nominally good news for Kohls. He doesn’t get an injunction against future enforcement, but he now has a judicial declaration that he’s in the clear.

But who else benefits from this ruling? It’s unclear if both of Kohls’ disclosures were necessary to reach this conclusion, or if the “parody” disclosure alone would have been sufficient. Either way, the deepfakes law is effectively a mandatory disclosure law, where any content is permitted so long as it displays the “parody” label, regardless of whether it would legally qualify as a parody or not.

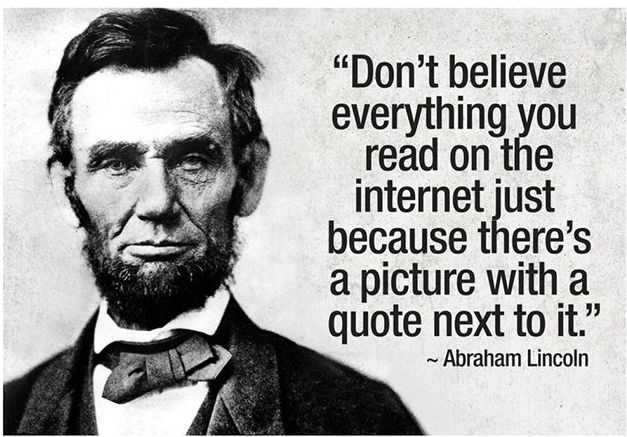

Indeed, the law makes it dangerous to produce inauthetic political content without the parody label, given that the legal determination of what constitutes a “parody” isn’t always predictable in advance. As an example, the court says this image shared by Rep. Franson is parody:

Is that a parody? Or is it just stupid? I don’t really know what I’m looking at or what message (parodic or otherwise) this communicates. So the court treats this as an easy case of “parody,” but is that obvious to you?

As more evidence that the parody defense is hard to anticipate, the court says that one of Kohls’ videos, which was retweeted by Musk without the parody disclosure and then further amplified by Rep. Franson, isn’t a parody because it wasn’t labeled or sufficiently obviously parodic otherwise. This video gives Rep. Franson standing to proceed with the constitutional challenge. However, the state took the advocacy position that the video was obviously parodic, and if they were willing to back that with enforcement resources, the video poses substantial legal risk to all who touch it.

(Note: Kohls’ video is third-party content that Rep. Franson retweeted, which means that Section 230 seems obviously in play here. However, the court doesn’t mention it because 230 isn’t relevant to the First Amendment challenge).

No Injunction

Minnesota enacted its anti-deepfakes law in 2023 and amended it in 2024. The court says that Rep. Franson’s retweet implicated the pre-amended version and thus her 16 month delay in challenging the pre-amendment law undermined the need for a preliminary injunction.

Implications

By using procedural tricks like standing and laches, the court sidestepped several key constitutional questions and many questions open. The court says that labeled parodies are unregulated by the law, but what about the First Amendment eligibility of unlabeled parodies or content that never qualifies as a parody? Also, does the mandatory labeling consequence of the law raise its own Constitutional problems? And, though not a part of the Constitutional challenge, what about Section 230’s role in all of this?

By using procedural tricks like standing and laches, the court sidestepped several key constitutional questions and many questions open. The court says that labeled parodies are unregulated by the law, but what about the First Amendment eligibility of unlabeled parodies or content that never qualifies as a parody? Also, does the mandatory labeling consequence of the law raise its own Constitutional problems? And, though not a part of the Constitutional challenge, what about Section 230’s role in all of this?

Given these unresolved issues, this statute has not yet received a clean bill of health. Indeed, the fact that a similar California law was enjoined is a major warning about the Constitutional lack-of-merits of the Minnesota law. (This court acknowledges Kohls’ role in enjoining the CA law (see FN 3), but never once engages with that opinion substantively).

Prof. Hancock’s Expert Report

Stanford Communications Prof. Jeff Hancock filed an expert report supporting Minnesota’s law, but that report did not go well.

Prof. Hancock used Generative AI to help draft the report. The Generative AI hallucinated citations (as it is known to do), and he didn’t catch the fake citations. As a result, he submitted an erroneous expert report.

Prof. Hancock used Generative AI to help draft the report. The Generative AI hallucinated citations (as it is known to do), and he didn’t catch the fake citations. As a result, he submitted an erroneous expert report.

The irony is palpable. On the one hand, the report demonstrates first-hand the risks that inauthentic content can pose to important social processes like court proceedings. On the other hand, if even Minnesota’s expert finds Generative AI useful to preparing important material in support of the state’s policies, perhaps the court ought to question the state’s anti-AI motives with extra scrutiny.

In a separate opinion from the preliminary injunction decision, the court rejects Prof. Hancock’s request to resubmit his corrected expert report. This proves inconsequential to the case outcomes, at least for now, because the court still denies the preliminary injunction request. Still, I see the court’s discussion as a good reminder that expert witnesses must use Generative AI with special care (or not use it at all) because any uncaught errors will be devastating to the expert’s credibility.

The court repeatedly expresses critical views of Prof. Hancock’s report:

- “The irony. Professor Hancock, a credentialed expert on the dangers of AI and misinformation, has fallen victim to the siren call of relying too heavily on AI—in a case that revolves around the dangers of AI, no less.”

- “Professor Hancock submitted a declaration made under penalty of perjury with fake citations. It is particularly troubling to the Court that Professor Hancock typically validates citations with a reference software when he writes academic articles but did not do so when submitting the Hancock Declaration as part of Minnesota’s legal filing. One would expect that greater attention would be paid to a document submitted under penalty of perjury than academic articles.”

- “The Court thus adds its voice to a growing chorus of courts around the country

declaring the same message: verify AI-generated content in legal submissions!” - “Professor Hancock’s citation to fake, AI-generated sources in his declaration—even with his helpful, thorough, and plausible explanation—shatters his credibility with this Court….the Hancock Declaration’s errors undermine its competence and credibility.” [NB: It’s never good for an expert witness’ long-term viability as an expert witness when a court say that the expert witness has “shattered his credibility.” I’m assuming all future litigation opponents will cite this language against Prof. Hancock’s future expert reports.]

- “The consequences of citing fake, AI-generated sources for attorneys and litigants are steep. Those consequences should be no different for an expert offering testimony to assist the Court under penalty of perjury.”

The court stresses that expert reports are subject to perjury standards (e.g., “signing a declaration under penalty of perjury is not a mere formality”) but, like I’ve raised before regarding the penalty of perjury language in 17 USC 512(c)(3), do expert witnesses ever actually get prosecuted for perjury? Or is that more of a theoretical risk? I don’t want to see more expert witnesses prosecuted for perjury, but I wonder if there’s a disconnect between the court’s emphasis and what’s happening in practice.

Incredibly, this isn’t my first blog post on expert reports gone awry due to Generative AI. In October, I wrote about an expert report who used Generative AI to calculate asset values in a non-reproducible way, which caused the court to question the report’s reliability and accuracy. It may seem odd to see multiple Generative AI issues with expert reports in such a short timeframe, but recall that typically an expert report faces a an opposing legal team and counter-experts with significant motivations to point out holes in the report.

Case Citations: Kohls v. Ellison, 2025 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 4953 (D. Minn. Jan. 10, 2025) (preliminary injunction denial) and Kohls v. Ellison, 2025 WL 66514 (D. Minn. Jan. 10, 2025) (Prof. Hancock’s report rejected).