Resolving Conflicts Between Trademark and Free Speech Rights After Jack Daniel’s v. VIP Products (Guest Blog Post)

By Guest Blogger Lisa P. Ramsey

[Lisa P. Ramsey is a Professor of Law at the University of San Diego School of Law. She writes and teaches in the trademark law area, and recently wrote a paper with Professor Christine Haight Farley that focuses on speech-protective doctrines in trademark infringement law.]

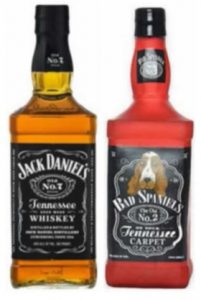

Many trademark attorneys and professors hoped the Supreme Court would provide more guidance on how to resolve conflicts between trademark and free speech rights in Jack Daniel’s Properties, Inc. v. VIP Products LLC, a dispute involving a “Bad Spaniels” dog toy parody of Jack Daniel’s brand of whisky. One question was whether the Court would approve of the speech-protective “Rogers test” for infringement created by the Second Circuit in 1989, and expanded by the Ninth Circuit during the last few decades. If another’s mark is used within the title or content of an expressive work, the Rogers test prevents a finding of infringement under 15 U.S.C. § 1114(1) or 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a)(1)(A) of the federal trademark law (commonly known as the Lanham Act) if this unauthorized use of that mark (1) is artistically relevant to the underlying work, and (2) does not explicitly mislead regarding the source or content of the work. The other issue in Jack Daniel’s was whether VIP could invoke the “noncommercial use of a mark” exemption from dilution liability in 15 U.S.C. § 1125(c)(3)(C) by claiming its humorous use of the Jack Daniel’s marks was not pure commercial speech because it poked fun at the company in the Bad Spaniels design.

Many trademark attorneys and professors hoped the Supreme Court would provide more guidance on how to resolve conflicts between trademark and free speech rights in Jack Daniel’s Properties, Inc. v. VIP Products LLC, a dispute involving a “Bad Spaniels” dog toy parody of Jack Daniel’s brand of whisky. One question was whether the Court would approve of the speech-protective “Rogers test” for infringement created by the Second Circuit in 1989, and expanded by the Ninth Circuit during the last few decades. If another’s mark is used within the title or content of an expressive work, the Rogers test prevents a finding of infringement under 15 U.S.C. § 1114(1) or 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a)(1)(A) of the federal trademark law (commonly known as the Lanham Act) if this unauthorized use of that mark (1) is artistically relevant to the underlying work, and (2) does not explicitly mislead regarding the source or content of the work. The other issue in Jack Daniel’s was whether VIP could invoke the “noncommercial use of a mark” exemption from dilution liability in 15 U.S.C. § 1125(c)(3)(C) by claiming its humorous use of the Jack Daniel’s marks was not pure commercial speech because it poked fun at the company in the Bad Spaniels design.

Unfortunately, the Court left many important questions unanswered in Jack Daniel’s and admitted that its “opinion is narrow” when it vacated the judgment below and remanded the case. My post summarizes the Court’s ruling and discusses its implications for brand owners, companies that sell parody products, and anyone interested in trademark law. Contrary to the view of some commentators, I also argue that the Jack Daniel’s opinion suggests the Court believes the First Amendment imposes significant limits on the scope of trademark rights. While there are problems with certain parts of the decision, including the Court’s ruling on the dilution claim, much of the language in the decision is speech-protective.

The Trademark Infringement Claim

A new gateway requirement for application of the Rogers test. In its June 8, 2023 opinion written by Justice Kagan, a unanimous Court declined to decide whether it is ever appropriate to apply the Rogers test—or any threshold First Amendment filter—in a trademark infringement lawsuit before allowing the case to “proceed to the Lanham Act’s likelihood-of-confusion inquiry.” It held “only that it is not appropriate when the accused infringer has used a trademark to designate the source of its own goods—in other words, has used a trademark as a trademark.” An example is use of “Nike” or the Nike swoosh logo to identify and distinguish the source of sneakers.

Thus, the Court did not provide guidance on several hotly contested issues in the Jack Daniel’s case, including: (1) whether the Rogers test can only be invoked in infringement disputes involving uses of marks in the title or content of traditional artistic and literary works (like movies, songs, or books), or any time a mark is used in an expressive work to communicate ideas or viewpoints (such within a parody displayed on the surface of a toy or T-shirt); (2) if the first prong of the Rogers test—the artistic relevance of the use—should be eliminated from the test; or (3) what evidence or factors should be considered by courts when they determine what uses of marks explicitly mislead as to the source or content of the expressive work. (See the briefs and amicus briefs filed in the Jack Daniel’s case, and Part I of my paper with Professor Farley.)

It is clear after Jack Daniel’s that Rogers’ threshold test for infringement liability cannot apply to a “‘quintessential trademark use’ like confusing appropriation of the names of political parties or brand logos.” As noted by Professor Jake Linford, the examples used by the Court when it discusses application of the Rogers test focus on uses in the title or content of artistic works (not on T-shirts). Thus, trademark owners may argue that this supports the argument that Rogers can only be applied in trademark disputes involving these types of expressive works with titles after Jack Daniel’s. On the other hand, some of the Justices were concerned during oral argument about allowing the display of political expression on T-shirts. Moreover, the Court does not say that VIP’s display of the design in a decorative manner on the product itself is a source-identifying use of the mark that would disqualify VIP from invoking the Rogers test.

Instead, the Court concludes that VIP is using the Bad Spaniels design as a mark to identify the source of its own goods because (1) in its complaint for declaratory judgment filed in this lawsuit, VIP claimed it both owns and uses the Bad Spaniels trademark and trade dress for its dog toy; (2) VIP displayed its spaniels dog face above the stylized phrase “Bad Spaniels” in a location on the cardboard hangtag attached to the toy that the Court deemed to be a source-identifying trademark spot; and (3) while it did not register the “Bad Spaniels” name or design, VIP has consistently argued in other court litigation that it owns common law or registered trademark rights in the names and/or trade dress of other dog toys sold in its Silly Squeakers line of toys. As I noted on Twitter, nothing in the opinion suggests that the display of parodies, jokes, or other messages on the surface of toys, T-shirts, or other types of expressive merchandise would, by itself, constitute a trademark use of another’s mark or trade dress. This is a speech-protective result.

Concerns about the Rogers test. While the Court did not disapprove of application of the Rogers test, it also did not approve of use of this speech-protective test (unlike the Congressional members of the House Judiciary Committee: see the “Balancing First Amendment concerns” section of the legislative history for the Trademark Modernization Act of 2020). Also, Justice Gorsuch wrote a concurring opinion (joined by Justices Thomas and Barrett) which said that “it is not entirely clear where the Rogers test comes from,” “it is not obvious that Rogers is correct in all its particulars,” and “serious questions” were raised about the test. Importantly, the Court’s discussion of the source-identifying function of trademarks, repeated emphasis on source confusion as the principal harm in trademark law (see, e.g., the type of confusion “most commonly in trademark law’s sights”, “the bête noire of trademark law”, and the “cardinal sin under the law”), and discussion of the United We Stand America opinion suggests the Justices may like Rogers’ focus on preventing uses that mislead about a product’s source or which falsely state the identity of a commercial or noncommercial speaker.

On the other hand, the Court did not suggest anywhere in the opinion that considering the artistic relevance of the allegedly-infringing use was the correct approach when evaluating an infringement claim. During the Jack Daniel’s oral argument, some of the Justices seemed wary of having judges or juries determine what is “art” or what uses of trademarks are “artistically relevant” in trademark disputes. The Court might be open to supporting a modified version of the Rogers test, or a different “threshold First Amendment filter” in infringement disputes, which does not require the use to be artistically relevant but which focuses on preventing source confusion and false statements about the trademark owner’s relationship to the accused infringer’s products. (Professor Farley and I propose such a test in Part III of our paper after we discuss the Rogers test in Part I and other speech-protective trademark doctrines like parody in Part II.)

Parody. Another part of the Jack Daniel’s opinion which protects expressive values in trademark law is the Court’s approval of use of the defensive common law doctrine of parody in infringement disputes. If a mark is used to parody or make fun of a trademark owner, this “expressive aspect” of the use should influence the likelihood of confusion analysis. Per the Court, the “kind of message matters in assessing confusion because consumers are not likely to think that the maker of a mocked product is itself doing the mocking.” Parody doctrine can apply when a similar mark is used as a designation of source, such as in the Chewy Vuiton case. Even if Rogers does not apply, the Court said that a “trademark’s expressive message—particularly a parodic one, as VIP asserts—may properly figure in assessing the likelihood of confusion.” A successful parody “create[s] contrasts, so that its message of ridicule or pointed humor comes clear. And once that is done (if that is done), a parody is not often likely to create confusion. Self-deprecation is one thing; self-mockery far less ordinary. So although VIP’s effort to ridicule Jack Daniel’s does not justify use of the Rogers test, it may make a difference in the standard trademark analysis.” Thus, on remand, VIP could still win on the infringement claim.

Motions to dismiss are allowed in trademark disputes. Importantly, the Court did not set forth a multi-factor likelihood of confusion test that must be applied to determine whether a certain use is “likely to cause confusion” under the Lanham Act, such as the Second Circuit’s Polaroid test or the Ninth Circuit’s Sleekcraft test. Nor did it state that lower courts must discuss and apply each of the factors in these types of fact-specific tests (such as the subjective intent of the accused infringer) when they evaluate infringement claims under the standard likelihood of confusion analysis. Moreover, the Court clarified that trial courts can dispose of frivolous trademark infringement claims as a matter of law on a motion to dismiss under the Rogers test and the standard likelihood of confusion test: “That is not to say (far from it) that every infringement case involving a source-identifying use requires full-scale litigation. Some of those uses will not present any plausible likelihood of confusion—because of dissimilarity in the marks or various contextual considerations. And if, in a given case, a plaintiff fails to plausibly allege a likelihood of confusion, the district court should dismiss the complaint under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6).” This language strongly protects speech interests, as the cost of discovery and trial may encourage accused infringers to settle instead of fight for their right to use truthful and nonmisleading language or designs in connection with their goods or services.

Source-identifying uses of marks. The Court said that “trademark law generally prevails over the First Amendment” when another’s mark or a confusingly similar mark is used to identify the product’s source. For such source-designating uses, “the First Amendment does not demand a threshold inquiry like the Rogers test. When a mark is used as a mark (except, potentially, in rare situations), the likelihood-of-confusion inquiry does enough work to account for the interest in free expression.” This part of the Jack Daniel’s opinion is problematic from a free speech perspective. The standard likelihood of confusion analysis may not adequately protect the First Amendment rights of an entity or person that uses language as a mark in a way that communicates the primary dictionary meaning of the words, or some other informational or expressive message unrelated to the party complaining about a trademark violation. For example, the Ninth Circuit held an accused infringer’s trademark use of “Empire” and “Punchbowl” did not infringe under the Rogers test. Unfortunately, the Court ignored these two cases when it said that lower courts have confined application of the Rogers test to cases where the mark is not used to designate a product’s source. This type of non-referential use of another’s mark is arguably one of the “rare situations” where the First Amendment requires “a threshold inquiry like the Rogers test.”

One question after Jack Daniel’s is whether the Court’s holding that only non-trademark uses of marks can qualify for the Rogers test applies to other speech-protective trademark doctrines created by judges to balance trademark and free speech rights in trademark infringement disputes. The Court’s statement that its opinion was “narrow” suggests the answer is no, but footnote 1 says: “To be clear, when we refer to ‘the Rogers threshold test,’ we mean any threshold First Amendment filter.” As Professor Farley and I discuss in Part II of our paper, several circuits require a commercial use of the mark for infringement (or an exception for noncommercial speech) and dismiss lawsuits without applying all of the likelihood of confusion factors if the unauthorized use of the mark is not commercial speech. In addition, in the Ninth Circuit, the doctrines of nominative fair use (discussed in Toyota v. Tabari) and aesthetically functional use by the defendant (applied in LTTB LLC v. Redbubble, Inc., aka the Lettuce Turnip the Beet case) do not require courts to evaluate all of the Sleekcraft likelihood of confusion factors or address the issue of likelihood of confusion.

Importantly, the Court did not say that trademark rights always trump First Amendment rights when a mark is used as a designation of source. (During oral argument, Jack Daniel’s attorney suggested trademark enforcement laws are always consistent with the First Amendment.) The Court only held that the Rogers test or any other “threshold First Amendment filter” that prevents application of “the Lanham-Act’s likelihood-of-confusion inquiry” requires a non-trademark use of the mark. Thus, use of the mark otherwise than as a designation of source may not be required if a judge-made trademark doctrine is a speech-protective interpretation of the “likely to cause confusion” language in the statute. For example, Tabari says that the Ninth Circuit’s three-factor nominative fair use “test ‘evaluates the likelihood of confusion in nominative use cases.’” The Court’s new rule may also not apply if the speech-protective doctrine can be characterized as a statutory defense to infringement. For example, 15 U.S.C. 1115(b)(8) allows the defending party to argue “[t]hat the mark is functional” in a trademark lawsuit. While courts usually focus on whether the plaintiff’s mark is functional when applying this law, the statute does not prevent courts from invoking an as-applied aesthetic functionality defense like in LTTB when the defendant only uses the plaintiff’s mark in a decorative manner on its own goods. As the Lanham Act’s text does not require application of all of the factors in traditional multi-factor likelihood of confusion tests like Polaroid or Sleekcraft, lower courts can probably confine the statement in footnote 1 to the Rogers test or any First Amendment threshold test that purports to replace the “likely to cause confusion” test for infringement in the Act.

Consumer survey evidence. Another important speech-protective part of the Jack Daniel’s decision is the concurring opinion written by Justice Sotomayor and joined by Justice Alito. They urge lower courts to “treat the results of [consumer] surveys with particular caution” and not give “uncritical or undue weight to surveys.” Surveys which reflect only confusion about whether parodies require the trademark owner’s permission, or misunderstandings about the law, should not “drive the infringement analysis.” This “would risk silencing a great many parodies, even ones that by other metrics are unlikely to result in the confusion about sourcing that is the core concern of the Lanham Act.” Justices Sotomayor and Alito are also concerned about the chilling effect of litigation in trademark disputes involving expressive uses of another’s mark: “Well-heeled brands with the resources to commission surveys would be handed an effective veto over mockery….This would upset the Lanham Act’s careful balancing of ‘the needs of merchants for identification as the provider of goods with the needs of society for free communication and discussion.’ . . . Courts should thus ensure surveys do not completely displace other likelihood-of-confusion factors, which may more accurately track the experiences of actual consumers in the marketplace. Courts should also be attentive to ways in which surveys may artificially prompt such confusion about the law or fail to sufficiently control for it.”

The Trademark Dilution Claim

With regard to Jack Daniel’s claim for dilution by tarnishment of its famous marks, VIP could not invoke the exemption from dilution liability for parody, criticism, or commentary in 15 U.S.C. § 1125(c)(3)(A) because that provision does not apply if the defending party is using the mark “as a designation of source for [its] own goods or services.” The Ninth Circuit held, however, that VIP’s dog toy qualified for the noncommercial use of the mark exemption in 15 U.S.C. § 1125(c)(3)(C) because the Bad Spaniels design conveyed a humorous message about Jack Daniel’s product. The Supreme Court disagreed with the circuit court’s approach on the ground that it “negated Congress’s judgment about when—and when not—parody (and criticism and commentary) is excluded from dilution liability.” The Court explains that it is not deciding “how far the ‘noncommercial use’ exclusion goes.” Thus, it provides no guidance on whether “noncommercial use” refers to uses of another’s mark that do more than solely propose a commercial transaction or if it includes mixed commercial-noncommercial speech that is deemed fully protected under the First Amendment per the Supreme Court’s test in Bolger v. Youngs Drug Products.

“Given the fair-use provision’s carve-out,” the Court explains that “parody (and criticism and commentary, humorous or otherwise) is exempt from liability only if not used to designate source. Whereas on the Ninth Circuit’s view, parody (and so forth) is exempt always—regardless of whether it designates source. The expansive view of the ‘noncommercial use’ exclusion effectively nullifies Congress’s express limit on the fair-use exclusion for parody, etc.” The Court concludes: “On dilution, we hold only that the noncommercial exclusion does not shield parody or other commentary when its use of a mark is similarly source-identifying.”

Some commentators have stated that the Court held in Jack Daniel’s that non-trademark use of the mark is always required to invoke both the parody fair use and the noncommercial use of the mark exemption from dilution liability. (For example: “neither of these exclusions apply when the mark is being used as a source-identifier” and “if a trademark dilution claim is based on the use of a challenged mark ‘as a mark,’ then it is not protected by the statutory noncommercial exclusion to trademark dilution, even if that challenged use is parody.”) This is wrong. Unlike in the parody exemption to dilution liability, the Lanham Act’s text does not limit the noncommercial use of the mark exemption to uses of marks other than as a designation of source. It could still apply to a dilution claim if the defending party claimed trademark rights in (1) a title for a television series (such as “Empire”), (2) the name of a political or religious organization, or (3) a political phrase for T-shirts. The Justices did not add a non-trademark use of the mark requirement to the text of 15 U.S.C. § 1125(c)(3)(C) which applies in every trademark dispute. Such a rule would clearly be inconsistent with the text and Congress’ intent to only require use “other than as a designation of source” in 15 U.S.C. § 1125(c)(3)(A).

The Court’s holding does appear, however, to create a new judge-made limit on the noncommercial use of a mark exception if the language or design is being used as a designation of source in parody, criticism, or commentary about the trademark owner. An example is Steve Elster’s claim for trademark rights in the political message “Trump Too Small” for T-shirts. If the owner of the “Trump” marks for various products sued him for dilution by tarnishment, Elster cannot invoke the statutory exemption from dilution liability for noncommercial use of the mark after the Jack Daniel’s decision since he is using the political phrase as a mark to criticize or comment on the trademark owner. Moreover, the language in Jack Daniel’s suggests that entertainment and publishing companies can no longer take advantage of the categorical exemption for noncommercial use of a mark if they claim trademark rights in a title for a series of works that contain parody, criticism, or commentary about the trademark owner or its products. This exemption is also unavailable to political and religious groups that adopt a source-designating name that contains criticism of or commentary about the owner of a famous mark.

It is surprising that the Court added an atextual non-trademark use requirement to the “[a]ny noncommercial use of a mark” provision when famous marks are used within parodies, criticism, and commentary, especially since there is an alternative way to interpret the speech-protective rules in 15 U.S.C. § 1125(c)(3). Congress could have intended a “belt and suspenders” approach here. Under this speech-protective interpretation of the dilution statute, the parody fair use and noncommercial use of a mark exemptions to dilution liability both apply to non-trademark uses of famous marks in noncommercial parodies, criticism, or commentary. Only the noncommercial use of a mark exception can apply, however, if the mark is being used as a mark in a parody or other commentary about the trademark owner and that speech is noncommercial under the Court’s First Amendment jurisprudence. It is unfortunate the Court decided to interpret these exclusions from dilution liability in a narrow way when a trademark dispute involves parody, criticism, or commentary about a famous trademark like Jack Daniel’s.

Is Jack Daniel’s a Speech-Protective Trademark Opinion?

While the Court’s interpretation of 15 U.S.C. § 1125(c)(3)(C) is problematic, other parts of the Jack Daniel’s decision are definitely speech-protective. As noted above, the opinion suggests courts should focus on the harm of source confusion in trademark law and pay attention to the source-identifying function of trademarks when First Amendment interests are implicated in a trademark dispute. Courts can take into account the expressive aspects of the accused infringer’s use in all trademark infringement disputes under the Act. They can also dismiss lawsuits that do not contain plausible allegations of a likelihood of confusion early in a lawsuit.

Moreover, the Justices’ decision to not allow courts to apply the Rogers test to source-identifying uses of marks could protect freedom of expression and fair competition in trademark law. This holding in Jack Daniel’s will likely discourage applications to register political and social messages, parodies, satire, jokes, mashups, memes, and other words or images that convey information, ideas, or viewpoints, as trademarks for dog toys, T-shirts, and other types of expressive merchandise. Trademark registrations for informational, expressive, or decorative subject matter can chill expression protected by the First Amendment and be invoked to stifle use of that language or design in the same way by competitors. Arguably this type of expression should remain in the public domain available for use by everyone in connection with their goods or services unless it is protected by another intellectual property law. Such words and symbols are also less likely to function as a source-identifying mark. Thus, registering or protecting trademark rights in this context will not further trademark law’s goal of facilitating the communication of truthful information about a product’s source.

Some contend that language in the Court’s Jack Daniel’s opinion “seem[s] to suggest that . . . trademark law should simply step in front of the 1st Amendment.” (Mike Masnick at TechDirt) Others note “it’s troubling that the Court went directly from concluding that source-identifying trademark uses fall within trademark law’s ‘heartland’ to concluding that no further First Amendment scrutiny was needed.” (Cara Gagliano at Electronic Frontier Foundation) I agree with EFF that “First Amendment interests may warrant heightened protection even for source identifiers when they’re attached to expressive works,” such as “Punchbowl News.” (EFF filed an amicus brief in Punchbowl, Inc. v. AJ Press, LLC, and I signed a professors’ amicus brief in that case.) Paul Levy at Public Citizen suggests that the Second Circuit’s approach to evaluating the explicitly misleads prong of the Rogers test, “under which First Amendment interests place a thumb on the scale in evaluating likelihood of confusion,” is one way to address the concerns of Justices Gorsuch, Thomas, and Barrett that the speech-protective rule in Rogers “be grounded in the language of the statute.” While the Ninth Circuit’s version of the Rogers test has advantages and is arguably a speech-protective interpretation of the text of the infringement statutes, in Part III of our paper Professor Farley and I propose the adoption of a new, broader fair use test to use in infringement disputes that is consistent with the statute’s text.

After the Jack Daniel’s decision, companies that sell dog toys or other expressive merchandise that parodies brands should consider not applying to register this expression as a trademark, and not displaying the trademark symbol (™) next to a phrase or design that incorporates another’s mark on a label, hangtag, or in another trademark space or trademark spot. Entertainment and publishing companies should think carefully before applying to register the title of a television or book series that includes another’s mark. While political organizations and individuals can express noncommercial messages that incorporate the marks or names of others, the defensive doctrines available to them in trademark law may be limited if those nonprofit groups or people attempt to register this language as a mark for their goods or services. If an expressive work incorporates another’s mark, attorneys and their clients should be aware of the risks of claiming trademark rights in that expression in a complaint filed with a court, a cease-and-desist letter sent to a competitor, or a take down request submitted to an online marketplace, search engine, or social media company that seeks to remove another’s products, advertisements, or posts.

One final thing I found interesting about the Jack Daniel’s opinion is that the Court’s discussion was similar in organization to the Court’s constitutional scrutiny analysis from its First Amendment jurisprudence. The Court first discussed the purposes of trademarks and trademark enforcement laws. Then it talked about the fit between these goals and the Court’s new gateway requirement for application of the Rogers test, which requires a non-trademark use of the mark. Finally, the Court discussed whether its new limitation on application of the test in Rogers would harm expression protected by the First Amendment. This approach is consistent with my argument in A Free Speech Right to Trademark Protection? and Free Speech Challenges to Trademark Law After Matal v. Tam that legislatures, courts, and trademark offices think about the questions set forth in the Court’s intermediate and strict scrutiny analysis when they create, revise, or interpret trademark laws in a manner consistent with the First Amendment.

In briefs filed in trademark disputes, litigants should consider discussing the purposes of the specific trademark law, how that law directly and materially furthers those goals, and whether and how the law harms truthful and nonmisleading expression protected by the First Amendment. Moreover, if the law regulates expression based on its viewpoint, such as trademark dilution law, the accused infringer should consider challenging the constitutionality of that law because the court must consider this issue if it does not rule in favor of the defending party on other grounds (such as the exemptions for parody fair use or noncommercial use of the mark). As the dilution by tarnishment provision is a trademark law that applies to offensive expression just like the laws in Tam and Brunetti, perhaps the Jack Daniel’s case will return to the Supreme Court for a determination of whether that viewpoint-based law is an unconstitutional regulation of expression protected by the First Amendment.