Hashtags Are Not Trademarks—Eksouzian v. Albanese (Guest Blog Post)

By Guest Blogger Alexandra Roberts

[Eric’s note: Prof. Roberts is a trademark expert at the University of New Hampshire School of Law. She’s writing a paper on hashtags as trademarks, a new topic of growing importance. When I saw this ruling, I immediately thought of her.]

The parties in this case were originally partners who sold portable vaporizer pens, but they parted ways under a cloud of suspicion. A July 2014 settlement agreement restricts both parties’ use of the term “cloud” in connection with the sale of their products: Defendants may only use “cloud” as part of a unitary mark; Plaintiffs may not use a unitary mark that places “cloud” next to any of several proscribed terms. Consistent with the TMEP, “unitary trademark” is defined as a trademark in which “the elements are so closely aligned and situated that the average consumer would view the group of words or symbols as a single trademark.”

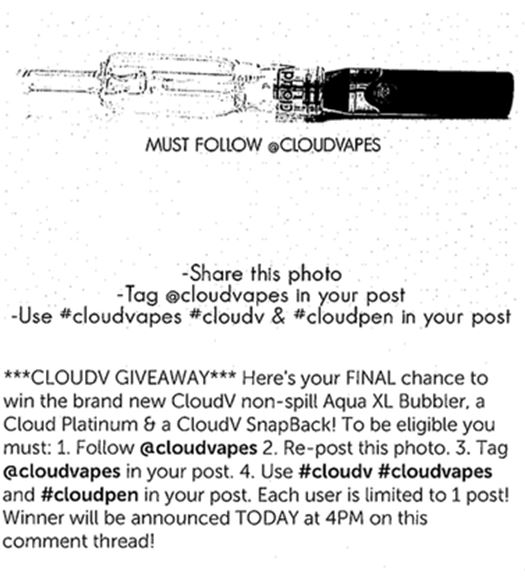

Just two months after settling, though, the parties were back in court. Among other allegations, Defendants claim Plaintiffs violated their obligation to avoid unitary marks that pair “cloud” with “pen” or “penz” when they used the hashtags #cloudpen and #cloudpenz on social media, including tagging images on Instagram and requiring that fans who want to enter sweepstakes use those hashtags on their own posts, too (side note: the FTC wasn’t thrilled when Cole Haan ran this type of hashtag contest on Pinterest). Here is an example of a promotion using the hashtags:

The court must determine not only whether the hashtag phrases are unitary marks, but whether they’re marks at all, making this case one of the first to adjudicate whether and when hashtags can be trademarks.

Hashtag-related claims are beginning to find their way into trademark infringement complaints. Earlier this year, a federal court in Mississippi declined to dismiss a hashtag infringement claim based on a designer’s use of #fratcollection and #fraternitycollection after the designer parted ways with plaintiff Fraternity Collection LLC. The Ninth Circuit was also briefed on allegedly infringing trademark use that included a Twitter hashtag in Webceleb v. P&G, but it declined to opine on the hashtag in its (unpublished, nonprecedential) opinion.

The Eksouzian court flatly declares that hashtags are “merely descriptive devices, not trademarks, unitary or otherwise.” Quoting Plaintiffs’ brief, the court calls the hashtag “merely a functional tool [and] not an actual trademark” and holds that Plaintiffs didn’t breach the agreement when they used #cloudpen “as a hashtag,” its italics emphasizing that the use on Instagram was not as a trademark, and certainly not a unitary one.

Fair enough—if “cloud” and “pen” are both descriptive or generic terms for the parties’ vaporizers, then it reasonably follows that the use of the hashtag #cloudpen constitutes a statutory fair use of the phrase, rather than a trademark use. But while all parties concede “pen” meets that description, the court hasn’t established the same is true for “cloud.” I’m not a member of the target audience for portable vape sellers, but Google results suggest the use of “cloud” in connection with vaporizer pens may be exclusive to these two parties. More importantly, the opinion omits analysis of Plaintiffs’ use of #cloudpenz, even though Defendants own a federal registration for the word mark CLOUD PENZ for vaporizers and even though the court comments in a footnote that CLOUDPENZ would likely qualify as unitary, in contrast to Defendants’ CLOUD PEN design mark.

And not only are Plaintiffs using Defendants’ registered mark as a hashtag. Defendants also acknowledge using Plaintiffs’ registered mark, CLOUD VAPEZ, as one too. In their briefs, both parties characterize their use of the hashtags as references to each other’s products—essentially nominative fair uses. Plaintiffs argue tagging a post with a competitor’s product name brings more eyeballs to that post without creating confusion. They submit a report from a social media expert who opines that using a competitor’s product name that way is a common practice, analogous to “placing an advertisement on a billboard in view of a competitor’s retail establishment.” [Eric’s comment: Oh god, not the shitty Brookfield billboard metaphor again.]

Hashtags began their reign on social media as metatags that facilitate searching and enable users to organize content. If you want to peruse the millions of Instagram images tagged #LoveWins or pull up the latest #deflategate news on Twitter, you can type the hashtag into the site’s search box or click on it in an existing post to display all other content tagged with that phrase. To be blunt, I’ve never seen hashtags used as Plaintiffs’ expert describes, although Louis Vuitton recently sued a manufacturer who tags images of its knockoff bags with LV marks like #louisvuitton and #lv. I wouldn’t expect to see Burger King promote their new chicken fries by tagging an image #FieryChickenFries #Spicy #BurgerKing #McDonalds, though I would be less surprised to see it tag a competitor conversationally in a manner resembling traditional nominative fair use (“Our new #FieryChickenFries are not for the faint of heart. If you can’t handle the heat, try #McDonalds.”). [Eric’s comment: then again, Burger King did just try its McWhopper publicity stunt.]

It seems problematic that the court mostly ignores the #cloudpenz hashtag, which is harder to write off as descriptive fair use than #cloudpen is. And while some courts lump nominative and descriptive fair use together, no Ninth Circuit court is ignorant of the distinction. On the other hand, it’s possible that the court is conflating descriptive use with the absence of trademark use–in other words, a hashtag is only a piece of metadata and not a trademark, so even a highly distinctive trademark used in hashtag form would be deemed a “descriptive” use as the court employs that term. And despite holding that the hashtags don’t violate the settlement agreement, the court acknowledges in a footnote that “if consumer confusion is to be avoided, such uses are improvident and should stop.”

The court’s dicta that “hashtags are merely descriptive devices, not trademarks” suggests it believes hashtags are chronically incapable of serving as source-indicators. But that broad assertion is inconsistent with USPTO practice. Over 70 hashtags have been granted federal registration so far this year, with hundreds of others pending or published. (I call them “tagmarks” in a forthcoming article that sets forth a taxonomy of hashtags and explores their protectability in depth.) Registered tagmarks include those associated with major brands like KFC’s #HowDoYouKFC; Vanity Fair’s #VFSocialClub; Mucinex’s #BlameMucus; Glade’s #BestFeelings; and Volvo’s #SwedeSpeak. Seven new tagmarks were registered in the week Eksouzian came down alone. And while many tagmarks are used in connection with goods and services in meatspace, some are not. The trademark office has accepted screenshots of hashtags on social media as specimens sufficient to establish use in commerce—check out those submitted with the applications to register #LikeAGirl (Twitter); #Steakworthy (Facebook); #Hollywood Trends (YouTube); and #RembrandtCharms (Facebook and Twitter).

Results from a survey I conducted to gauge consumer perception of tagmarks suggest that the court is often right to be skeptical that a hashtag serves a trademark function. In many cases consumers perceive even registered tagmarks as mere hashtags that invite them to join a conversation on social media or enable them to organize posts on a given topic. In response to a question modeled after the classic Teflon survey for genericide asking whether, based on the image below, #BeUnprecedented was a hashtag or a trademark, only 5% of respondents chose “trademark” or “both,” while 83% classified it as a hashtag and 11% selected “neither” or “I don’t know.”

In other contexts, though, hashtags appear capable of indicating source or functioning as slogans protectable under trademark law. In the same survey, 87% of respondents classified #GetFried as a trademark or as both trademark and hashtag based on the below specimen:

The hashtag analysis in Eksouzian is premised on the court’s assumptions that a hashtag use is not a trademark use and a hashtag is not a trademark. But CLOUD PENZ is a registered mark, and #cloudpenz could be one too if Trademark Office practices are any indicator. The court quotes TMEP guidance on hashtags and purports to follow it, but doesn’t really–the Manual says only that the hash symbol does not render a descriptive mark distinctive, while the court seems to read into it a rule that a hashtag phrase must be merely descriptive. Hashtag jurisprudence is in its budding infancy, with federal courts, federal agencies, corporate practices, and consumer perception pointing in seemingly disparate directions. In Eksouzian, the court declines the opportunity to cut through the cloud of smoke surrounding tagmarks’ protectability and enforceability and hash out a better understanding of whether and when hashtags function as trademarks.

The main holding in the case pertained to Defendants’ use of this CLOUD PEN mark, which Plaintiffs contended was not unitary and therefore violated their agreement:

The court concurred with Plaintiffs, trotting out classic precedent LIGHT ‘N LIVELY as an example of a mark whose elements are inseparable and “create a unitary visual impression,” unlike the elements of Plaintiffs’ CLOUD PEN logo. The holding is correct given the relative size in which “pen” appears and the separateness of the terms, but it’s worth noting that the agreement itself actually cited “Cloud Penz® and Cloud Pen™” as examples of permissible unitary marks, so it’s clear how Defendants were led astray. Making compliance with a settlement agreement hinge on laymen’s understanding of the esoteric legal term “unitary mark” seems half-baked given the subjective nature of that label. The unitary mark rule is hard for even trademark examining attorneys to apply in a consistent way, so it’s unsurprising that these parties disagreed as to whether this use of the phrase ran afoul of their agreement.

_____

Eric’s supplement: we approached both sides’ counsel for public comments. Plaintiff’s counsel Kevin Shenkman wrote:

As you might expect, we’re very happy with the result. Up until very recently, I have never had to seek court enforcement of a settlement agreement – in 13 years of practicing law and more settlements in that time than I could count.

Perhaps the favorable result is tainting my view, but I would not deal with the “unitary mark” issue differently if I had to do it over again. Because of the hostilities between the parties, and the unusual and erratic behavior of the defendants, we had to resort to reference to “unitary marks” because inclusion of more detail would likely have killed the deal on one side or the other. I was comfortable with the reference to “unitary mark” at the time of drafting the settlement agreement, and it turns out that phrase accomplished my clients’ purposes.

Defense counsel Dan DeCarlo wrote:

We represented the defendants who had settled a lawsuit with another entity that was using the word CLOUD for electronic cigarettes. Our client too, was using CLOUD for electronic cigarettes and so the settlement agreement sought to define the way each party could use CLOUD in their markings. Under the terms of the settlement agreement, our client was permitted to use CLOUD as long as CLOUD was used in close proximity to another word like PEN (PEN is a generic term for an electronic cigarette) and provided that the mark formed a “unitary mark” as we defined “unitary mark” in the settlement agreement. Importantly, the settlement agreement adopted the TMEP definition of a unitary mark but added an important caveat that “the size and specific relationship of CLOUD with the other word or words used in close association with CLOUD is within Defendants’ discretion except that the word coupled with CLOUD must be in close proximity and be readable.” Ultimately, the Court held in a motion to enforce the settlement agreement that the mark our client adopted after the settlement agreement was not a “unitary mark”. (The mark at issue is noted at footnote 2 of the Court’s Order).

We respectfully disagree with the Court on two grounds. First, we think the Court failed to give credence to the fact that the parties expressly created their own definition of a “unitary mark” by again, expressly noting that it was within the discretion of the defendants to dispose the word or words used with CLOUD however defendants chose so long as the wording was readable. There is no question that Defendants met this standard and indeed, the Court agreed. As the Court noted, “Thus, the size and relationship between words used in the creation of Defendants’ unitary mark is indisputably a matter over which Defendants have broad discretion. Words used in Defendants’ unitary mark are not required to be on the same line, in the same font, or of equal size.“ (Order Page 4 ll 24-27). So in the first instance, it is unclear how the Court found that the mark entailed design elements that were close in proximity and readable, yet still found that the mark at issue was not a “unitary mark” as the Parties defined unitary mark. Second, even if the sole analysis was to assess whether the mark was a “unitary mark” as that mark has been interpreted by Courts and the TTAB, we disagree with the Court’s conclusion. The court held that the mark “does not create a unitary visual impression….Defendants’ design would lead an ordinary consumer to encounter the mark as three separate elements, not an ‘indivisible symbol.’” (Order P. 10 ll 5-10). There was no evidence submitted to support this holding, and the Court did not point to any evidence suggesting that an ordinary consumer would adopt this view. Moreover, a simple review of the mark illustrates that it does present a singular visual impression. It is not linear text, but rather is a design mark that stacks three visual elements: (1) a fanciful design of a cloud (2) the word “cloud” and (3) the word “pen”. The design is visually centered so that the cloud design leads to the more pronounced word CLOUD and down to the lesser pronounced generic term “pen”. The disposition of “pen” is of lesser importance in the visual nature of the mark because pen is the generic portion. The mark is unitary in the sense that a consumer would see the design as a whole imparting a singular impression. The Court seemed to place great emphasis on the fact that there were “no lines or designs (to) unite “CLOUD” with “pen” (Order P. 10 ll 10-11). But we would respectfully suggest that the Court ignored the plain visual impression of the mark which is that it was a single and unified symbol that could only be reasonably viewed as a single impression. That there were no lines connecting the various elements of the mark is not a necessary feature of a unitary mark. And, as noted previously, the settlement agreement sought to eliminate the very kind of second guessing that is now going on by expressly providing the defendants with the discretion to dispose the various elements in whatever size the defendant wanted so long as the elements were proximate and readable.

Case citation: Eksouzian v. Albanes, 2015 WL 4720478 (C.D. Cal. Aug. 7, 2015)

Pingback: CLIP-ings: August 28, 2015 | CLIP-ings()

Pingback: Are Hashtags Trademarks? | Geek Law()