Internet Access Providers Can Be Contributorily Liable for Subscribers’ Infringements–Sony Music v. Cox

As I’ve previously written, for many years after the DMCA passed, everyone assumed that 17 USC 512(a) completely shielded Internet access providers from liability for subscribers’ copyright infringements. Then, about a dozen years ago, the rightsowners coerced Internet access providers to adopt the “Copyright Alert System,” which treated rightsowners as trusted flaggers (whether or not they deserved that status) and required Internet access providers to deploy a “six strike” system–with, presumably, the final consequence being termination of Internet access. If 512(a) provided full immunity, the Copyright Alert System was unnecessary and pernicious to both IAPs and their subscribers. With the CAS’s demise, both sides essentially bet that the courts would side with them. At this point, it looks like the rightsowners are getting the better end of that bet. Rightsowners have sued numerous IAPs, sometimes with shocking outcomes. This case, for example, resulted in a $1B judgment against an IAP (Cox), calculated at a sky-high $100k of statutory damages per infringed work.

Why isn’t 512(a) resolving these cases? Rightsowners claim that Internet access providers don’t terminate repeat infringers quickly enough and therefore don’t meet the 512(a) prerequisites. But IAPs have good reason to tread cautiously. Rightsowner notices of claimed infringements (NOCIs) aren’t verified, and losing Internet access can affect people’s employment, education, engagement with government services, safety, and more. But without 512(a) protection, IAPs can be in existential peril.

Cox previously lost the DMCA 512(a) battle in the BMG case. With the safe harbor unavailable, the remaining question on the table for the Fourth Circuit is whether the rightsowners properly established their prima facie cases of contributory and vicarious infringement. The appeals court rejected the vicarious claims but upheld the contributory claims. That’s enough to vacate the $1B damages award and remand the case for a trial on damages. However, the news is not great for Cox because it could get tagged for huge damages on remand.

* * *

The court describes how (following the CAS’s demise), the rightsowners’ agent MarkMonitor flooded Cox with automated NOCIs. Cox made some countermoves to this flood:

[Cox] capped the number of notices it would accept from RIAA, eventually holding it at 600 notices per day. It took no action on the first DMCA complaint for each subscriber, limited the number of account suspensions per day, and restarted the strike count for subscribers once it terminated and reinstated them. MarkMonitor sent Cox 163,148 infringement notices during the claim period. Over that time, Cox terminated 32 subscribers for violation of its Acceptable Use Policy, which prohibits copyright infringement among other things. By comparison, it terminated over 600,000 subscribers for nonpayment over that same time.

Vicarious Infringement

The appeals court says that Cox lacked the requisite “direct financial interest” in subscribers’ infringements. This is a defense-favorable ruling and explanation.

The court recaps past cases:

the crux of the financial benefit inquiry is whether a causal relationship exists between the infringing activity and a financial benefit to the defendant. If copyright infringement draws customers to the defendant’s service or incentivizes them to pay more for their service, that financial benefit may be profit from infringement. But in every case, the financial benefit to the defendant must flow directly from the third party’s acts of infringement to establish vicarious liability.

The “draw” theory, dating back to the 1990s, divorces the doctrine from actual, you know, “financial interest.” That’s how the Ninth Circuit decided that Napster had a “direct financial interest” in users’ infringements, even though Napster never made a dime of revenue. If simply attracting customers interested in copyright material satisfies the “direct financial interest” prong, then this factor functionally evaporates.

Instead, the court qualifies that the financial benefit “must flow directly” from the users’ infringement. What does that phrase mean exactly? I have no idea. It sounds similar to proximate causation, which is a fancy legal term that also doesn’t have a definitive meaning. Generally, the court is saying there needs to be a nexus between the infringement and the profit, and it won’t be enough to just show how copyrighted works were a draw to users.

While “direct financial interest” can occur even without the defendant earning any profits (see, again, Napster), the court draws a hard line in the sand:

To prove vicarious liability, therefore, Sony had to show that Cox profited from its subscribers’ infringing download and distribution of Plaintiffs’ copyrighted songs. It did not.

These rightsowners tried hard to make that case.

The rightsowners pointed out that Cox didn’t terminate some infringing subscribers because they were paying lots of money (one customer was paying $317/month for Internet access–what???). The court replies:

The continued payment of monthly fees for internet service, even by repeat infringers, was not a financial benefit flowing directly from the copyright infringement itself….Cox would receive the same monthly fees even if all of its subscribers stopped infringing. Cox’s financial interest in retaining subscriptions to its internet service did not give it a financial interest in its subscribers’ myriad online activities, whether acts of copyright infringement or any other unlawful acts. An internet service provider would necessarily lose money if it canceled subscriptions, but that demonstrates only that the service provider profits directly from the sale of internet access. Vicarious liability, on the other hand, demands proof that the defendant profits directly from the acts of infringement for which it is being held accountable

The rightsowners argued that Cox became a haven for infringing subscribers. For example, “Sony highlights evidence that roughly 13% of Cox’s network traffic was attributable to peer-to-peer activity and over 99% of peer-to-peer usage was infringing.” The court replies:

the evidence falls considerably short of demonstrating that customers were drawn to purchase Cox’s internet service, or continued to use that service, because it offered them the ability to infringe Plaintiffs’ copyrights. Many activities of modern life demand internet service. No one disputes that Cox’s subscribers need the internet for countless reasons, whether or not they can infringe. Sony has not identified evidence that any infringing subscribers purchased internet access because it enabled them to infringe copyrighted music. Nor does any evidence suggest that customers chose Cox’s internet service, as opposed to a competitor’s, because of any knowledge or expectation about Cox’s lenient response to infringement.

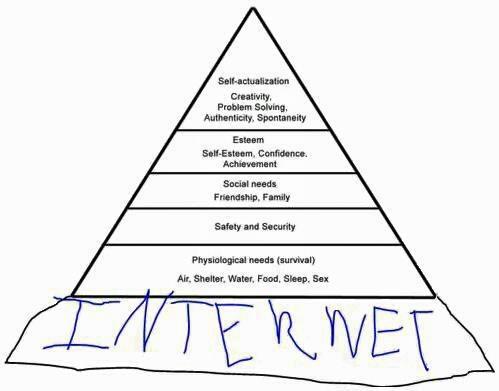

This discussion reminds me of this meme:

People aren’t paying Cox for the privilege to infringe. They are paying for an essential utility. (This is why the remedy of terminating Internet access does not fit the alleged violation).

The rightsowners next argued that Cox offered tiered pricing based on download speeds, which allegedly encouraged infringing subscribers to pay more for bandwidth-intensive downloads. The court responds:

None of this raises a reasonable inference that any Cox subscriber paid more for faster internet in order to engage in copyright infringement. As Sony’s expert testified, other data intensive activities include legally streaming movies, television shows, and music, as well as playing video games. Subscribers may have purchased high speed internet for lawful streaming and downloads or because their households had many internet users; Sony’s expert didn’t claim to know why any customer purchased a higher tier of service. Sony has not identified any evidence that customers were attracted to Cox’s internet service or paid higher monthly fees because of the opportunity to infringe Plaintiffs’ copyrights

It will be interesting to see how other courts parse the court’s conclusion on direct financial interest, especially the nexus requirement articulated by this court. I think this ruling will lead to more defense wins. Clearly, rightsowners must do more than simply point to the defendants’ cash flow to establish “direct financial interest” in the infringements.

Contributory Infringement

The standard common law contributory infringement test: “one who, with knowledge of the infringing activity, induces, causes or materially contributes to the infringing conduct of another.”

In a prior case (BMG v. Cox), the Fourth Circuit held the scienter requirement was satisfied when Cox had “knowledge that infringement was substantially certain to result from the sale of internet service to a customer.” (Cleaned up).

This standard is problematic for IAPs. Unlike web hosts, who can cut off future infringements by removing the infringing item, IAPs have to estimate a subscriber’s future propensity to infringe based on having received unverified NOCIs about past activities. Now IAPs are experts on the psychology of IP recidivism?

In the lower court, Cox focused on the inadequacies of MarkMonitor’s NOCIs. On appeal, Cox complained that NOCIs don’t provide sufficient predictive power about future recidivism. The court says Cox waived that argument by not making it below. Bummer. Perhaps a future IAP defendant can pick this thread up.

The lower court accepted the jury’s finding that Cox materially contributed to the subscribers’ infringements because it was a but-for cause of their activity. Ugh. The appeals court agrees:

The evidence at trial, viewed in the light most favorable to Sony, showed more than mere failure to prevent infringement. The jury saw evidence that Cox knew of specific instances of repeat copyright infringement occurring on its network, that Cox traced those instances to specific users, and that Cox chose to continue providing monthly internet access to those users despite believing the online infringement would continue because it wanted to avoid losing revenue. Sony presented extensive evidence about Cox’s increasingly liberal policies and procedures for responding to reported infringement on its network, which Sony characterized as ensuring that infringement would recur. And the jury reasonably could have interpreted internal Cox emails and chats as displaying contempt for laws intended to curb online infringement. To be sure, Cox’s anti-infringement efforts and its claimed success at deterring repeat infringement are also in the record. But we do not weigh the evidence at this juncture. The evidence was sufficient to support a finding that Cox materially contributed to copyright infringement occurring on its network and that its conduct was culpable.

The jury found that Cox “willfully” contributorily infringed. The court upholds that conclusion.

Damages. The court says it can’t tell if the jury’s damages award was affected by its conclusion that Cox both willfully contributorily infringed and vicariously infringed. Thus, the appeals court remands the case for a new trial to calculate statutory damages predicated solely on the willful contributory infringements.

Implications

Who Won This Ruling? Nominally, Cox got the relief it asked for: the court vacated the damages judgment. But did Cox “win” this ruling?

At the damages retrial, a jury could award identical (or even higher) statutory damages than the amount vacated. A copyright defendant owes damages if it infringes, whether that’s directly, contributorily, or vicariously. Thus, the fact that Cox infringed only one way (contributory) instead of two ways doesn’t inherently lower the damages amount. The jury can award up to $150,000 per work infringed contributorily (a total potential maximum of about $1.5B).

The retrial jury will be instructed that Cox willfully committed contributory infringement. In the damages retrial, Cox can present a wide range of evidence, but it cannot disprove its willfulness. Thus, it’s possible the jury would “throw the book” at Cox for its unrebutted willfulness.

On the other hand, statutory damages of $100k per infringed work is ridiculously high. Another jury may not overcompensate Sony so grossly. If the jury were to settle on, say, $30k per infringed work (still a ridiculously high amount), that would slice the damages by $700M.

Due to this range of possible outcomes, it wouldn’t surprise me if the parties settle before the retrial. Any settlement will save Cox hundreds of millions compared to the first jury award.

Either way, Cox may have won this round, but it has lost the war. It is a willful contributory infringer on the hook for likely hundreds of millions of dollars in this case and vulnerable to other lawsuits with large financial risk. This is a bad outcome for Cox and all IAPs.

512(a) Has Failed. With the hindsight of history, I believe the DMCA drafters didn’t properly understand the interplay between 512(a), which provides a bright-line immunity to IAPs, and the obligation to terminate repeat infringers, which doesn’t make sense in the IAP context. The repeat infringer termination condition should have been limited to hosting situations, not extended to Internet access. Because the two concepts are linked, the 512(a) scheme contains a fatal flaw that rightsowners have identified and exploited. The logical conclusion of rulings like this is that IAPs must terminate Internet access quickly based on robotically generated unverified claims of infringement that are intrinsically error-prone, regardless of how devastating the loss of Internet access will be to the subscriber. This would be a terrible policy outcome that I bet would shock the DMCA drafters.

512(f) Has Failed. Cox restricted MarkMonitor to stem its flood of dubious NOCIs. 512(f) was supposed to prevent such tidal waves by ensuring that rightsowners did their homework to validate infringements before submitting the notice. But because courts have acquiesced to robotically generated NOCIs, regardless of error rate, 512(f) doesn’t provide the insulation for IAPs that I bet the DMCA drafters anticipated.

The DMCA has Failed. Overall, the DMCA safe harbors tried to channel disputes in very specific ways. Leave IAPs out of it. Put web hosts in the position to intervene at the rightsowners’ requests, unless the targeted user counternotices, in which case the matter should be sent to the courts for judicial supervision. After a quarter century, this scheme has structurally failed in several ways. First, rightsowners and services have developed private ordering solutions that bypass any of the DMCA due process-like protections for users. Second, rightsowners have expanded the zone of target defendants to go “upstream” of web hosts and pressure defendants who don’t have any DMCA safe harbor protection. As depicted in this chart, the rightsowners increasingly ignore the middle category of defendants and instead target entities on the right column liable, where the DMCA doesn’t reach. By shifting the battlegrounds outside the DMCA’s scope, the rightsowners negate the DMCA’s structure.

Rightsowners are Relentless. Targeting non-DMCA-protected defendants was the premise of SOPA. Though the SOPA bill died in 2012, the rightsowners are still seeking to encode substantial chunks of SOPA through the courts. In other words, 25+ years after the major stakeholders struck the deal that got codified in the DMCA safe harbors, the rightsowners are still trying to make the deal more favorable to them. Rightsowners will invest whatever resources it takes to eventually win. This ruling shows how much progress they’ve made.

Case Citation: Sony Music Entertainment v. Cox Communications, Incorporated, 2024 WL 676432 (4th Cir. Feb. 20, 2024)