Another Failed Legal Challenge to Zillow’s Zestimate–EJ MGT v. Zillow

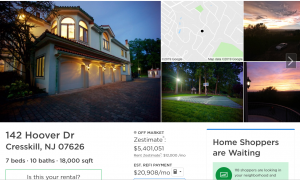

The plaintiff is a real estate investor. It bought and fixed up a property in New Jersey. Afterwards, the plaintiff listed the property for $7,788,000. On the property’s Zillow page, right below the listing price, Zillow displayed its zestimate of $3,703,597. The court doesn’t fully explain the disparity, but it’s probably due to Zillow not accounting for the renovations and the difficulty estimating prices for high-end properties with limited comps. Still, the disparity between the listing price and the zestimate may have spooked some buyers–though the plaintiff did not allege that the zestimate is wrong.

The plaintiff is a real estate investor. It bought and fixed up a property in New Jersey. Afterwards, the plaintiff listed the property for $7,788,000. On the property’s Zillow page, right below the listing price, Zillow displayed its zestimate of $3,703,597. The court doesn’t fully explain the disparity, but it’s probably due to Zillow not accounting for the renovations and the difficulty estimating prices for high-end properties with limited comps. Still, the disparity between the listing price and the zestimate may have spooked some buyers–though the plaintiff did not allege that the zestimate is wrong.

Zillow apparently offers some real estate brokerage companies the ability to relocate the zestimate on the property’s Zillow page, so that the zestimate doesn’t appear directly below the listing price and instead appears in a more obscure place. The court doesn’t explain why Zillow offers this relocation feature only to some brokers; nor is it clear how relocating the zestimate benefits consumers.

Based on Zillow’s disparate offering of the relocation option to competitor brokers, the plaintiff brought an antitrust claim against Zillow. Unsurprisingly, it fails.

The Sherman Act claim fails because the plaintiff made inconsistent allegations: it alleged both that it wants the zestimate removed but that the zestimate is a critical piece of information to consumers. The fraud and product disparagement claims fail because, among other things, the zestimates are non-actionable opinions (cite to the district court ruling in Patel v. Zillow). The tortious interference claim fails because, among other things, the plaintiff didn’t specifically identify any dissuaded buyer.

As I wrote in my post on Patel, “I treat zestimates as entertainment more than truth, much like going to an astrologer.” Perhaps Zillow could do more to make sure consumers fully understand the strengths and weaknesses of the zestimates. However, this plaintiff’s antitrust claims aren’t a helpful mechanism to force those disclosures.

Case citation: EJ MGT LLC v. Zillow Group, Inc., 2019 WL 981649 (D.N.J. Feb. 28, 2019)

Bonus: The Seventh Circuit affirmed the Patel v. Zillow district court ruling. It’s an Easterbrook opinion, so it’s characteristically bold and unforgiving. He writes: “Zestimates are opinions, which canonically are not actionable.” He continues:

Suppose plaintiffs are right to think that the Zestimates for their properties are too low. Removing them from the database would skew the distribution, because all mistakes that favored property owners would remain, not offset by errors in the other direction. Potential buyers would be made worse off. Suppose instead that plaintiffs are wrong—that they have overestimated the value of their properties, while the Zestimates are closer to the truth. Then removing them from the database would not just skew the distribution but also increase the average error of estimates. Potential buyers of plaintiffs’ properties would be deprived of valuable knowledge. Finally, suppose that plaintiffs are behaving strategically—that they know the Zestimates to be accurate (or at least closer to the likely sales price than are plaintiffs’ asking prices). Then removing their parcels from the database, or “correcting” the Zestimates to match plaintiffs’ asking prices, would degrade the accuracy of the database as a whole without any offsetting benefits to the real-estate market. In general, the accuracy of algorithmic estimates cannot be improved by plucking some numbers out of the distribution or “improving” others in ways that depart from the algorithm’s output. The process is more accurate, overall, when errors are not biased to favor sellers or buyers.

Patel v. Zillow, No. 18-2130 (7th Cir. Feb. 8, 2019)