Copyright Office Won’t Register ‘Middle-Finger Pictogram’ As Literary Work–Ashton v. Copyright Office

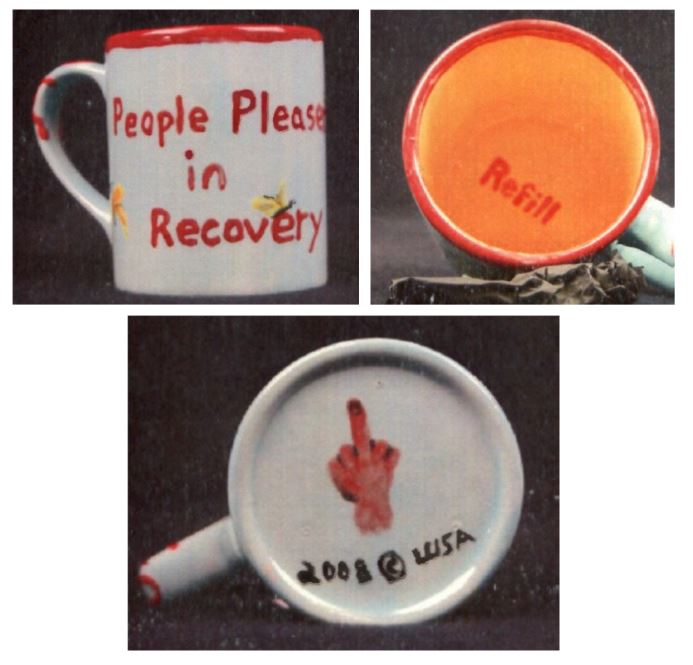

Ashton created a coffee mug displaying the words “People Pleaser in Recovery” on the outside, the word “Refill” on the inside bottom, and a single-fingered salute on the outside bottom:

Ashton applied for copyright registrations for 2D artwork and a literary work. According to Ashton, the “text” supporting the literary work copyright consisted of the phrases “people pleaser in recovery” + “refill” + the “pictogram” of the raised middle finger; those elements allegedly comprised a 3-line poem, e.g.:

People Pleaser in Recovery

Refill

🖕

Ashton claimed the middle-finger drawing qualified as text, not 2D artwork, because it is a “word, indicia or symbol” (though the actual Sec. 101 definition of “literary work” says “words, numbers, or other verbal or numerical symbols or indicia”). The Copyright Office repeatedly refused the registration for text. Its final decision said:

- the individual text components are uncopyrightable words/short phrases/familiar symbols. Thus, the middle-finger pictogram isn’t copyrightable as text on a standalone basis (or is de minimis even if it is)

- the three-line poem doesn’t clear Feist’s creativity standard

- the artwork, including the middle finger, could be registered as such

Most of us would have accepted the artwork registration and moved on. Ashton instead challenged the Copyright Office ruling in court, which goes nowhere. This is a pretty straightforward application of the Copyright Office’s words and short phrases rule, which is well supported by Feist.

Unfortunately, the court sidesteps the more interesting question of whether a pictogram can qualify as a literary work. To me, it seems unlikely that any hand gesture, however visually depicted, should ever qualify as a literary work.

This case indirectly addresses the copyrightability of emojis, something I analyze in my Emojis and the Law paper (secret tip: I posted a new draft! I’ll blog about it soon). According to this case, individual emojis shouldn’t qualify as literary works despite their semantic meanings; however, some emojis will qualify for copyright protection as 2D artwork, like this middle-finger pictogram apparently did.

A related trademark issue: is “Bob’s [car emoji]” inherently distinctive because of the (currently novel) combination of Bob with the car emoji, or will the Trademark Office require disclaimer of the emoji (like it would if the word “cars” was used), which would necessitate secondary meaning to register the trademark? I think the latter outcome makes more sense because the car emoji and the word “car” are semantically substitutable.

Case citation: Ashton v. U.S. Copyright Office, 1:16-cv-02305-APM (D.C.D.C. March 8, 2018)

Bonus Hidden Track: Oyewole v. Ora, 1:16-cv-01912-AJN (S.D.N.Y. March 8, 2018). On the same day, a court ruled against a copyright plaintiff claiming that songwriters infringed the phrase “party and bullshit.” Instead of relying on the short phrase doctrine, the court assumes that the phrase is copyrightable and dismisses the complaint on fair use grounds. I guess all’s well that ends well, but fair use analyses look strange when applied to microworks like this. Among other things, the court says the defendants made transformative uses because the copyright plaintiff used the phrase in a politically rebellious song to mock partiers, while the defendants used the phrase as a rallying cry to celebrate partying. (Cf. the Beastie Boys’ well-known 80s anthem “(You Gotta) Fight for Your Right (to Party),” which the band intended to be satirical but most listeners interpreted as aspirational).